The Trouble with Carbon Pricing

It has a face that only economists can love?

We economists have long been enamored with carbon pricing. The concept is simple and sensible. If the economic damages from greenhouse gas emissions can be reflected in market prices, powerful market forces will work for, versus against, the planet.

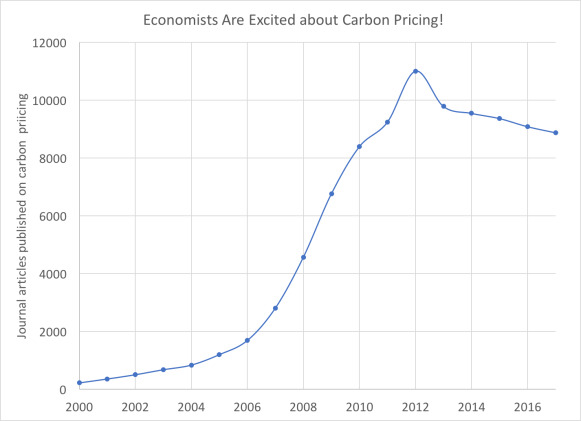

Over the past two decades, a growing number of economists have been working to refine and elaborate on this elegant idea. This chart shows the growing number of papers published on the topic:

Google scholar counts economics papers published on carbon pricing. Numbers were on the rise through 2012. Publications (and enthusiasm) have waned slightly in recent years.

It’s been easy to get economists excited about carbon pricing. But political constraints and widespread public misgivings have greatly complicated the translation from economic journals to real-world policy. Here in the U.S., there have been many failed attempts. And some of the hard-won successes have not endured.

Given this checkered past, and in the light of the new green idealism, many are questioning whether carbon pricing has any place in domestic carbon policy. I think carbon pricing has an essential role to play. But as we economist-types work to define and advocate for this role, we have to accept (versus ignore or wishfully assume away) some inconvenient truths.

Public opinion is shifting…but not fast enough

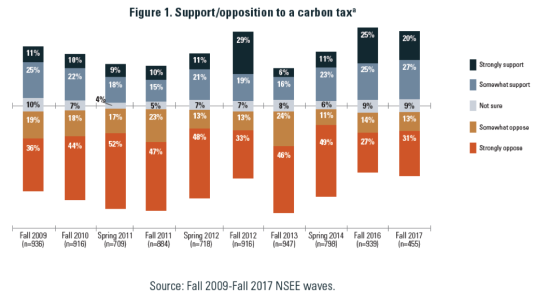

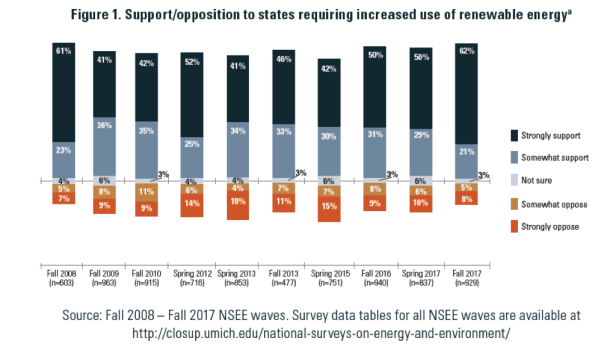

My former Michigan colleague Barry Rabe and his team have been tracking U.S. public opinion on climate policy since 2008. There’s a lot to unpack in these survey responses. I’ll highlight two key findings here.

First, carbon pricing consistently finishes last in the most popular climate policy competition. The figure below tracks public support for carbon pricing since 2009. The good news is that, in recent years, supporters are edging out opponents. But the not so good news is that a majority of opponents “strongly oppose” (orange bars) whereas the majority of proponents just “somewhat support” (light blue).

Source: National Survey on Energy and the Environment

Source: National Survey on Energy and the Environment

The contrast between carbon tax support (above) and support for clean energy requirements (below) is striking. Public support for renewable energy mandates has been strong (deep blue bars) and unwavering. In the most recent 2018 survey (not pictured), a majority (54%) strongly support renewable energy mandates while only 12% strongly oppose. In that same survey, corresponding carbon tax responses are 22% and 30%, respectively.

These voter-on-the-street policy preferences run counter to an economist’s sensibilities. With clean energy mandates, important low-cost abatement potential (such as fuel switching) goes untapped because mandates push clean technology versus penalizing the damages caused by fossil fuels. In other words, reliance on mandates (versus a carbon price) means the (short run) cost of achieving a given level of emissions abatement can be much higher than it needs to be.

Of course, the reality is that asking voters to pay higher energy prices in exchange for some ill-defined promise of future climate benefits is a tough sell. A political advantage of mandates is that they focus on the shiny goal versus the painful process that will get us there.

A second important takeaway is that framing (and revenue allocation) matters. If you ask people whether they support an increase in their energy bills, it’s not surprising that a majority of Americans recoil. But when the tax is tied to more salient benefits (e.g., renewable energy investments), survey responses start to inch closer to the popularity of renewable energy mandates. This is particularly true in recent years:

What if the revenue from the carbon tax was reinvested in renewable energy projects like solar or wind energy? Would you strongly support, somewhat support, somewhat oppose, or strongly oppose such a system?

Source: National Surveys on Energy and the Environment

Americans are willing to pay if focused on benefits versus costs

Survey responses are revealing. But even the most carefully worded survey question about a hypothetical can generate misleading indicators of what people will actually do when it comes time to vote a climate change policy up or down. So it’s worth looking at revealed policy preferences. What are the policies that Americans, or at least their political representatives, have actually been supporting. And at what cost?

The graph below charts the rocky track record of carbon pricing relative to the steady progress of renewable energy mandates in the United States. No state has managed to adopt a carbon tax. But in the mid-2000’s, we saw some exciting green shoots of carbon pricing via cap-and-trade. By 2011, however, more than half the states that had formally signed on to regional initiatives had backed out. In contrast, support for renewable energy mandates endures.

Source: Carbon pricing data taken from Barry Rabe’s excellent book “Can We Price Carbon?” Data on state-level RPS adoption taken from the National Conference of State Legislators.

The carbon prices over this time period were in the range of $2-$3/ton (RGGI) and $12-$15/ton (California). The renewable energy mandates operating over this period were much more expensive. In a backward-looking analysis, we analyzed renewable energy credit (REC) prices paid in 2010-2012, the time when carbon pricing participation was flagging but RPS support was growing. For solar PV investments, REC prices effectively conferred subsidies in the range of $100-$480 per ton of carbon abated. These high – but hidden – costs were being incurred in the same states that were dropping out of – or electing not to participate in – relatively inexpensive carbon pricing programs.

It’s worth noting that these cost comparisons focus on short-run marginal abatement costs and benefits. If we think that renewable energy portfolio standards can more effectively accelerate the large scale innovation and technological change that will be required to combat climate change, then these relative dynamic efficiency advantages would offset some of the additional costs.

Let’s make a green deal

No matter what you think about the Green New Deal, everyone’s talking about it. It points in a radical new direction with few details on how to get there. Discuss!

The GND is intentionally silent on the role of carbon pricing. But if it succeeds in re-energizing the discussion about federal climate change policy (I hope it does) a more pragmatic discussion of the all-important details will ensue. There’s no blueprint for success. But one lesson I think we’ve learned is that a public-facing focus on pricing carbon does not sell well in the mass market. And framing matters. If we lead with the rallying cry of “tax carbon!”, it’s hard to imagine that the politically durable carbon price we could negotiate would be set at a level that is close to commensurate with the climate change threat.

In contrast, Americans in states red and blue have demonstrated a willingness to pay more for green energy if they are focused on goal-setting defined in terms of tangible benefits. Mandates and prescriptive standards are not the most economically efficient solution. But their relative popularity makes them a durable second-best option.

If the public face of domestic climate policy must focus on popular and prescriptive mandates, there are ways to harness market forces in order to lower the costs of delivering on these goals and aspirations. Moreover, if a fraction of the ambition of the GND is retained in future domestic climate policy, we’ll need a way to pay for it. It may pain economists to see carbon pricing cast in a diminished backseat role. But given the political realities, we should work within the constraints these realities impose. And focus more of our energies on designing the best-possible second best.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith. “The Trouble with Carbon Pricing.” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, April 29, 2019, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2019/04/29/the-trouble-with-carbon-pricing/

Categories

Well-written piece on the carbon pricing paradox, Meredith. Agree with the empirical evidence of revealed preference for (statically less efficient) RPSs over carbon pricing. Still a lot of work to be done on why – good opportunity for survey and experimental practitioners. It’s worth all of us remembering, though, that the RPS/CES vs carbon pricing cage match is primarily about the power sector, which is becoming a smaller share of total emissions in most jurisdictions. Need to wrestle with the most effective mechanisms for transportation, heavy industry, buildings and land use.

If there are numbers, most of us will have to pay close attention over a period of time to understand the details. These are just some of the confusions I hear:

• Subsidies are free, taxes cost me money. Subsidies are particularly free if they subsidize my behavior. No one says these words, but listen, and find this is what many think. Somewhat less popular: we can’t be subsidizing the renewables we are mandating and subsidizing because they are cheaper than alternatives.

• Really popular today among those who always favored subsidizing their favored solutions, in arguing for the GND and against a GHG price: adding a price is an incremental solution and cannot be part of revolutionary to-be-defined changes going forward.

• The revenue goes where? There is the idea of many to refund to everyone. But what is not discussed is, “Let’s figure out how we want to tax ourselves. Do we want to pay less in the way of income or/and sales or/and social security/Medicare tax, and move those taxes over to addressing climate change?” Almost no one sees a GHG price as a clear choice over other taxes. Most people appear to assume that the taxes will disappear somewhere.

• What the market does is confusing, in part because we know that the market is companies acting without any rules in a lawless manner. It’s useful to provide examples to the public on the difference between market driven solutions and mandates/subsidies.

A partial list. And that doesn’t even count willful misunderstandings.

“The revenue goes where? There is the idea of many to refund to everyone.”

Karen, though unfortunately the term “revenue/neutral carbon tax” has prevailed in common usage, it’s an oxymoron. Unlike a tax, revenue-neutral programs don’t represent a “compulsory contribution to state revenue” – after fees, all collected revenue is returned to the public. More accurately, they’re described using James Hansen’s term “fee and dividend.”

“Almost no one sees a GHG price as a clear choice over other taxes.”

Fee and dividend is a GHG price but not a tax – the best of both worlds. Though it could be considered a re-distribution of wealth, I can already hear the wails of despair from conservative corridors should proponents try that approach.

Well at least economists are being more transparent with their Gruber-esque support for policies that their costs and motives from voters.

Meredith – very interesting piece. However, climate science is the only one where theories trump verified measurements!

Please see my piece below, published in local papers here:

Measurements over model predictions

Global warming is real, but very moderate. The warming over many decades has been measured by eleven independent groups of climate scientists who find the average rate to be 0.11 degrees Celsius per decade. NOAA, NASA-GISS, HADCRUT, and BEST-LBNL used land and sea-surface stations. NOAA, RSS and UAH analyzed satellite data. NOAA, UKMet, RICH and RAOBCORE analyzed balloon data.

Theoretical climate models predict an average GW of 0.27 C/decade, about 2.5 times the measured warming rate. In sciences other than climate measurements trump theory! But in climate science most establishment scientists use these much more alarmist model-predictions to propose and support increased funding for their positions, etc.

It is baffling that so many climate scientists and the media refuse to consider the verified measurements of warming. Eventually, they may face being accused of colluding in a massive, multi-billion-dollar global deception!

The recent IPCC report, SR1.5, asserts that, according to their model-predictions, we face a climate-crisis in 10-12 years! However, measurements give us about 60 years, if we do nothing. But we are doing much, and have the time and technology to reduce emission rates and hence warming rates, and push climate-crises into the next century, if not into oblivion!

Dr. F. Paul Brady, Retired Professor of Physics, UC Davis

Principal, BPF Investments/Charitable Investments

Office Ph: (530) 753-5929; Cell (530) 220-3593

43182 West Oakside Pl, Davis, CA 95618

“Global warming is real, but very moderate. The warming over many decades has been measured by eleven independent groups of climate scientists who find the average rate to be 0.11 degrees Celsius per decade. ”

Perhaps, but those measurements provide an incomplete picture. I’m not familiar with the models but it could be that the more moderate rate of increase in air temperature is the result of heat that’s absorbed as the surface ice sheets melt, as the seas warm and also transfer heat to subsurface ice melt, and as the land mass warms. Do the climate models incorporate these effects properly?

Rising air temperatures are one kind of threat, and rising sea levels are a different kind of threat.

Here are my two letters addressing the many errors in Dr. Brady’s articles in the Davis Enterprise:

https://www.davisenterprise.com/forum/letters/cant-dismiss-all-the-other-data/

https://www.davisenterprise.com/forum/letters/forecasts-differ-from-historical-data/

Unfortunately, this article offers no discussion of the leading proposal supported by more than 3,500 economists and embodied in the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act: a carbon tax (or fee) combined with lump sum dividends. Of course a carbon tax is a hard sell, but dividends may make it much easier. Polls show strong support from voters for carbon taxes levied on fossil fuel companies, suggesting that framing (taxing companies rather than individuals) is important. According to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communications, 63% of registered voters support Fee and Dividend, described as “requiring fossil-fuel companies to pay a fee on carbon pollution, and distributing the money collected to all U.S. citizens, in equal amounts, through monthly dividend checks.” That includes 78 percent of Democrats, 66 percent of independents and 39 percent of Republicans. Carbon taxes have proven popular in British Columbia thanks to revenue recycling (not a pure dividend scheme). A 2018 paper co-authored by Nicholas Stern concluded that “Uniform lump-sum recycling is favourable in more general circumstances since it may ensure broad public support.” Making Carbon Pricing Work for Citizens by David Klenert, Linus Mattauch, Emmanuel Combet, Ottmar Edenhofer, Cameron Hepburn, Ryan Rafaty and Nicholas Stern, Nature Climate Change (2018), DOI: 10.1038/s41558-018-0201-2. Recycling of carbon tax revenues was also endorsed as an effective approach in Carattini S, Carvalho M and Fankhauser S (2017) How to make carbon taxes more acceptable. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wcc.531.

Well put Jonathan. Meredith’s piece is interesting and makes good points about people’s behavior. But it highlights the need to be careful about drawing inferences from an incomplete set of questions. That is, as Jonathan points out no question was asked about people’s position on a plan that refunds all the carbon tax revenues to citizens. Nor does the set of questions include one that asks about people’s position when they’re told about all the hidden costs renewable portfolio standards. Seems to me one of the biggest problems is incomplete information, which others in this thread mention. And as others allude, maybe there is little chance of overcoming this information gap and people’s irrational behavior. I hope this isn’t true, and we can implement a more economically efficient and simple policy than a basket of command and control measures.

Maybe a different question should be asked. What does it mean if the public does not want to pay for carbon reduction? Mandating renewable generation, electric cars or other perceived solutions to carbon emissions does not change the cost. In fact, as implied above, it probably increases the costs. Could it be that people want change if it is free but do not really want to pay the cost? Could it be that people only want a carbon free future if the other guy is paying for it?

I will never forget when an influential politician, when talking about solar mandates, said it had nothing to do with a cleaner environment (or efficient use of funds). It had to do with California jobs. Perhaps that could be read as another way to pay for votes.

It all seems very disingenuous to me. If California really wanted a cleaner environment, why are there so many commuting such a long distance to work driving without a passenger?

I won’t pretend to understand all of the factors at work when people choose to commute long distances to work but I’ll speculate that two of them are a) the cost of housing closer to where their jobs are, and b) the perception that living in a less crowded area affords them and their families a better quality of life. Remember too that Meridith’s data suggests most people are either uninformed about the relative costs of carbon taxes vs. renewable mandates, or they’re irrational, or more likely both.

I’ve done both and as someone who is easily frustrated, the much higher cost of living closer to a job was more than offset by better mental and physical health, but not everyone is similarly situated.

Nicely done, Meredith. Recent discussions about Clean Energy Standards (with trading) for the power sector could be added to the mandates list and would be more efficient than an RPS if nuclear is included and even natural gas.

Very interesting.

There seems to be a minor glitch in the title of your first graph. I think it should say “Excited” instead of “Exited.”

Hate to be pedantic here, but in fact any regulation of carbon or other greenhouse gases makes it more expensive to use/emit fossil fuels, fluorinated gases, etc., and in effect puts a price on carbon.

Great blog. I love cap and trade, I love the idea of carbon taxes, I love economic efficiency. So what? It’s time for us economists to let it go and focus on enabling a less efficient but more feasible path to fighting climate change. There will be plenty for us to do to help make it happen.

Nicely articulated. Thank you.