Pricing Carbon Isn’t Enough

A GHG tax alone doesn’t solve the global need for low-cost alternative technologies

Economists seldom discuss climate change without someone opining that it is simply an externality that can be solved by putting a price on GHG emissions. In fact, a couple months ago a bi-partisan group of nearly 50 superstar economists released a statement in support of a U.S. carbon tax that would rise each year “until emissions reductions goals are met.” The statement says that this price on carbon will harness “the invisible hand of the marketplace to steer economic actors towards a low-carbon future.”

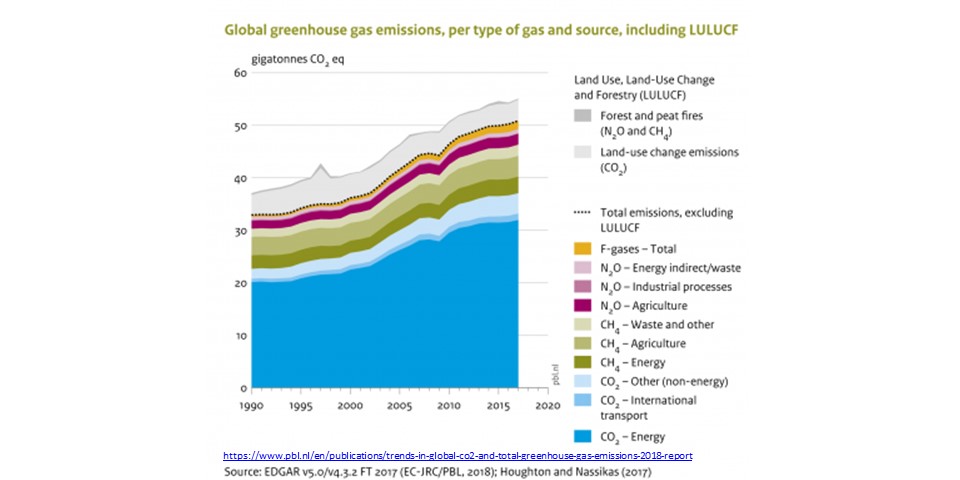

I’m as big an advocate of pricing GHGs as other economists working on climate change. Adding the cost of negative externalities to the price users pay is a very powerful way to bend consumption in a more responsible direction. That goes for GHGs as much as for traffic congestion, fine particle emissions, or plastic disposal. But when it comes to global climate change, pricing carbon isn’t a complete answer. The idea that we can ratchet up the tax until we hit the desired emissions doesn’t recognize that most of the global emissions are now coming from relatively poor countries. Politically, they are even less likely than the developed world to accept a large carbon tax. And economically, a big tax, given current technologies, would significantly slow their climb out of poverty.

The idea that we can ratchet up the tax until we hit the desired emissions doesn’t recognize that most of the global emissions are now coming from relatively poor countries. Politically, they are even less likely than the developed world to accept a large carbon tax. And economically, a big tax, given current technologies, would significantly slow their climb out of poverty.

Economists on the “just price carbon” train argue that the tax will encourage technological innovation that helps displace fossil fuels. That’s just straightforward economics. But straightforward economics also tells us that even if emissions are priced, there is a second market failure that the price won’t address: inefficient markets for innovation. Successful innovators typically can only capture a small share of the value they create for society. Most of the value of innovation is enjoyed by others in society. That is great for the many who get the benefits — and it generally increases the total benefits derived from a new idea — but it still reduces the incentive to create new ideas.

Most developed countries try to address this market failure with intellectual property (IP) laws that reward inventors by giving them a monopoly over the product for years or decades. The inventor can then profit by charging high prices and restricting sales of their product. That might be the best option for the latest mobile electronics, but it’s not a good approach when we need rapid diffusion of GHG-reducing technologies in poor countries. Furthermore, IP protection is complex and costly to use, and IP laws are weakly enforced or non-existent in most of the developing world.

All of which is why the U.S. and most other advanced economies explicitly subsidize knowledge creation – for instance, through grants to researchers and innovative entrepreneurs, creation of freely accessible data and libraries, and tax breaks for research and development expenditures by companies. Knowledge creation generates huge positive externalities that are not reflected when we simply “get the prices right” for goods and services in the economy.

Economists widely agree that this imperfection in the knowledge market leads to sub-optimal levels of innovation, but at this point in a climate change conversation, someone will ask whether this problem is any bigger in technologies to reduce GHGs than in any other market. If we got the prices right, wouldn’t markets at least have as much incentive to solve climate change as other challenges, such as curing diseases or creating more realistic video games?

Unfortunately, no. At least, not if other nations — particularly the low-income, developing countries where GHG emissions are growing fastest — don’t also get the prices right. The whole planet benefits when developing economies follow a low-carbon path, but most of those benefits do not go to a country that chooses that path. So, the most viable path to decarbonizing the developing world must include pushing the cost of reducing GHGs ever lower. Pricing up carbon (and other greenhouse gases) in wealthier countries helps, but if much of the world is unlikely to take that road, then we also need to be focused on innovating down the cost of alternatives.

Subsidizing innovation effectively is not easy. It means some degree of administratively picking winners among the many creative, or just crazy, ideas that are out there for eliminating GHG emissions. The process will be imperfect, mistakes will be made, and corruption can easily work its way in. Those are good reasons to do it carefully and monitor the programs closely. But they’re not good reasons to conclude that pricing emissions alone has the Good Economics Seal of Approval. The world we live in is nothing like the setting in which that would be true.

There is a lot of cheap fossil fuel left on the planet – and likely to get cheaper as some economies move to alternatives and reduce their demand. We need not just the wealthy developed countries to stop using it, but also the poor less-developed countries to grow out of poverty without it. Maybe those countries will voluntarily forgo the cheapest energy sources, but there isn’t much indication of that. Maybe wealthy countries will pay poor ones to get off the carbon path, but that also seems unlikely. So, policies that support innovation to lower the cost of carbon-free energy should be an explicit part of fighting climate change. Working in tandem with a robust carbon tax wherever it is politically possible.

I’m still tweeting energy news stories/research/blogs most days @BorensteinS

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin. “Pricing Carbon Isn’t Enough.” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, April 15, 2019, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2019/04/15/pricing-carbon-isnt-enough/

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Sorry to have appeared as anonymous in my last post — I’ll take the blame/credit for my thoughts. I hit the post button too soon!

Your comments suggest that a carbon tax should not be enacted. I don’t agree with that nor do I think Severin does either. What Severin is saying is that the tax alone will not be sufficient because it will not be adopted by the poor countries that will become the largest sources of GHGs.

However there is another strategy for supplementing a carbon tax. The developed nations can subsidize the adoption of renewables and GHG abatement measures. It may be cheaper and more economically efficient for the developed nations to provide these subsidies than to take on Draconian abatement measures at home.

Robert – my skepticism about the efficacy of a carbon tax as a key energy policy driver is twofold – just to riff on my previous comments: First can it get us “there” in a timely fashion. If one assumes we have a finite time window in which to act (we can argue about the details of what that needs to be in another forum) does a carbon tax provide the push to to get there in, say, 20 years? What evidence is there to suggest that we should put most of our energy policy eggs in that basket?

Are the technological innovation signals such a tax sends unambiguous enough that one can rely solely on that push or are there other energy and technology policies that are more important on which to spend political capital (arguably itself a finite resource)? That political capital is my second concern and at least from my non-economist, outside-looking-in perspective, I don’t see much that is encouraging about whether there is a political will to set up a carbon tax that is meaningful. A few countries are trying it – I believe Canada is in the midst of a legal wrangle over their attempt at a carbon tax – but I haven’t followed those details. The last time we touched the federal tax on gasoline (arguably similar to a carbon tax in trying to induce energy market behavior) was 1993 and the outcome was a one-time only increase in the tax not indexed to inflation. Indeed, we’ve moved ahead with out it, as there are specific (non-tax) policies (CAFE, for example) that have improved automobile energy efficiency and reduced emissions (which the current regime is trying to undo). Not to say that it shouldn’t be increased – not the least as a way to help pay for infrastructure repair and improvements (yes, I read the Energy Institute blog on EVs and gas taxes…).

Maybe a carbon tax effort is useful as a supplemental policy but I’m no longer convinced that its the key solution and I’m increasingly concerned that we don’t have the time to find out.

Glad to see that there is some economic apostasy creeping into the discussion about ‘carbon-tax-as-universal-solution-to-global-warming’ (or maybe its economists (finally) meet the real world…). It seems to me one could turn this question around and ask whether, in fact, the idea of a carbon tax as a major element in reducing/eliminating GHG emissions is overblown as a driver for technological innovation and, perhaps more importantly, whether the political capital required to establish a meaningful carbon tax is better spent elsewhere.

One the first point, this is what Borenstein seems to be saying – especially if one thinks that the window of opportunity to make significant inroads in reducing GHG emissions is narrow (some would argue its rapidly closing). So even if carbon were priced “right”, is the time constant for the necessary changes induced by such a tax too long (I think it is – or at least perilously so).

On the other hand, one can certainly point to the major inroads made by solar (mostly PV) and wind for electricity generation (as one example) – not only for new generation but displacing some of the worst actors – existing coal-fired power plants (despite Trump administration apoplexy). So how did it happen that the costs of new PV and wind are as low as they are – and trending even lower? Clearly governmental subsidies have played a role (despite some energy economists’ apoplexy) – as has funding for research in renewables. Are these better – and more politically tractable – economic (and otherwise) policies and they will get us “there” faster? My fear is that the ‘debate’ about a carbon tax is consuming most of the energy policy oxygen – starving other economic approaches that are potentially more directly targeted and with much shorter time constants.

The way to clean up the world is to offer an alternative source of clean power that is close to being competitive with natural gas. Nuclear fission has that potential at today’s natural gas prices if power plant cost could be reduced to $3,000/kW; if we had mature industries; if China and the US were each building dozens of standard design reactors per year. The manufacturers learning curve is a very powerful thing. A carbon tax could help get that process started.

We don’t have to wait for technologies to be cost effective with natural gas–solar and wind already are in the developed world vs. a NEW gas plant. Much of the issue is that we are trying to find technologies that have all-in costs lower than just the fuel costs of existing plants. That seems to be because we still have this silly idea that we should treat a single industry differently from all others by protecting their investments despite the fact that they earned regulated returns that match those of much riskier industries.

Current IP policy and laws isn’t a particularly good model in any case. Who wins the innovation contest, and with most other endowment and resource allocations, is at least as much as a lottery as being smarter. Our current policies have accelerated income inequality and undermined societies’ trust of their institutions. While it’s clear that we want a decentralized mode to encouraging innovation (I like to compare the economies of West and East Germany after 45 years of separation) we also need to change how we distribute the rewards of innovation.

The innovation we pursue for the developing world needs to be in low-capital dispersed solutions that allow the populace to be less tethered to a center. That they have skipped wired telecommunications is a good model. The developed world can facilitate this by encouraging distributed energy resources here, even if it costs more in the short term than continuing to rely on central generation plants.

Excellent point, Severin.

Thank you for looking after a fair solution to the global emissions problem.

Mayra Addison

Prof. Energy and environment, A Sustainable Approach

University of St Thomas

A tax is a negative reinforcement for not doing something – the high tax will therefore result in tax being avoided or evaded especially by less developed countries. Grants for innovation are positive reinforcement to bring long-term results. The negative gets you started; the positive keeps you going.

I think this article presents a brilliant insight,

Severin, you knocked it out of the ballpark – again.

Finally! Your last 2 sentences need to be memorized by all those addressing climate change (I added two words):

“So, PROGRAMS AND policies that support innovation to lower the cost of carbon-free energy should be an explicit part of fighting climate change. Working in tandem with a robust carbon tax wherever it is politically possible.”

Many thanks on shedding the light for those stuck on believing the carbon tax is the panacea.

Ed

Ha—academic economists can either say their grants for research serve no public purpose, or knowledge creation policies correct a market failure. Which is it?

Rob, your missing the alternative–we should just assume that we already have a perfect world accessible if we just quit mucking around with it…