Our 2023 Carbon Footprint

A few calculations led to surprising conclusions about how to reduce our household’s impact.

The holiday break is a great time to catch up with friends, try out some new dishes on my fabulous induction stove, see a movie or two, and ponder some issues that I didn’t get enough time to think about during the year. Many years ago, I spent part of the holiday break measuring the electricity usage of all the appliances in my house, which I reported in our first blog post of 2014.

This year, I did some calculations about our household’s GHG footprint. I got to thinking about the subject while writing a paper on “energy hogs”, which I discussed in two blog posts in August. After analyzing our utility bills, odometer readings, and air travel, what I found made me rethink the best steps to reduce our contributions to climate change. (I considered using one of the many online carbon calculators, but they are so opaque and embed so many simplifying assumptions that I decided to do some calculations myself.)

(Source)

Energy use at home

Our household consists of just my wife and myself. The dog and cat don’t use much hot water, have expressed no opinion on the thermostat setting, and seldom drive anywhere, so we aren’t going to count them.

Our electricity usage in 2023 was 6314 kWh. Using the standard California marginal emissions rate of 0.0004 tonnes (metric tons) of CO2 per kWh, that translates to 2.5 tonnes. That likely overstates the emissions, both because California’s marginal rate is falling as more renewables come on the grid and because we try to focus our consumption on the hours when renewables are plentiful. Though, like all of these calculations, it does not account for upstream CO2 and methane emissions in upstream production of fossil fuels.

—

Of the 6314 kWh, my best estimate is about 1100 kWh goes into our hot tub. I get the stink-eye from some folks for having a hot tub, though I have never been clear on why that particular consumption draws such ire. These calculations showed that the annual CO2 due to our hot tub is about the same as a one-way flight across the country (and I enjoy it a whole lot more).

The only thing we use natural gas for in our house is the furnace and the hot water heater. Our summer usage suggests that the furnace is likely over 85% of it. (The hot tub has its own electric heater.) Together, those consumed 677 therms of gas in 2023, which produced about 3.8 tonnes of CO2, though methane leaks in the distribution system may make its full greenhouse gas impact far larger. Still, even that is 50% more than all the electricity we used to run the clothes dryer, air conditioner (which actually only turns on 3-4 times a year), hot tub, fabulous induction stove, lights, computers, coffee maker, and everything else. Given that state and (current) federal agencies are all over the energy efficiency standards for these appliances, it makes me think that the biggest improvement may be beefing up insulation in our 1992-built house. Still, that is one of the most costly and challenging upgrades and the efficiency audit we got a decade ago suggested there isn’t much low hanging fruit there.

On the road

Compared to the average household, we don’t drive much. Between the two of us, and including mileage we put on rental cars and rideshares in 2023, we drove about 10,600 miles in total. We have hybrids that average around 40 MPG, so that is about 265 gallons of gasoline, which means a total CO2 emissions around 2.4 tonnes, roughly the same as our electricity.

—

My wife’s car is a 2019, but I drive a 2008 Prius and have thought about whether I should replace it with an EV. Here’s the calculation that convinced me not to: I put about 4000 miles per year on my Prius, at about 40 MPG, so it burns around 100 gallons per year, which emits around 0.9 tonnes of CO2. Doing those same miles with an EV would take about 1000 kWh and emit about 0.4 tonnes. Even if you put a societal cost of $200/tonne on those CO2 emissions – the high end of current estimates – the 0.5 tonne annual savings would be worth $100 per year. It’s hard to see how society’s resources are well spent producing a new EV at a cost of $20,000+ in order to save society $100 per year.

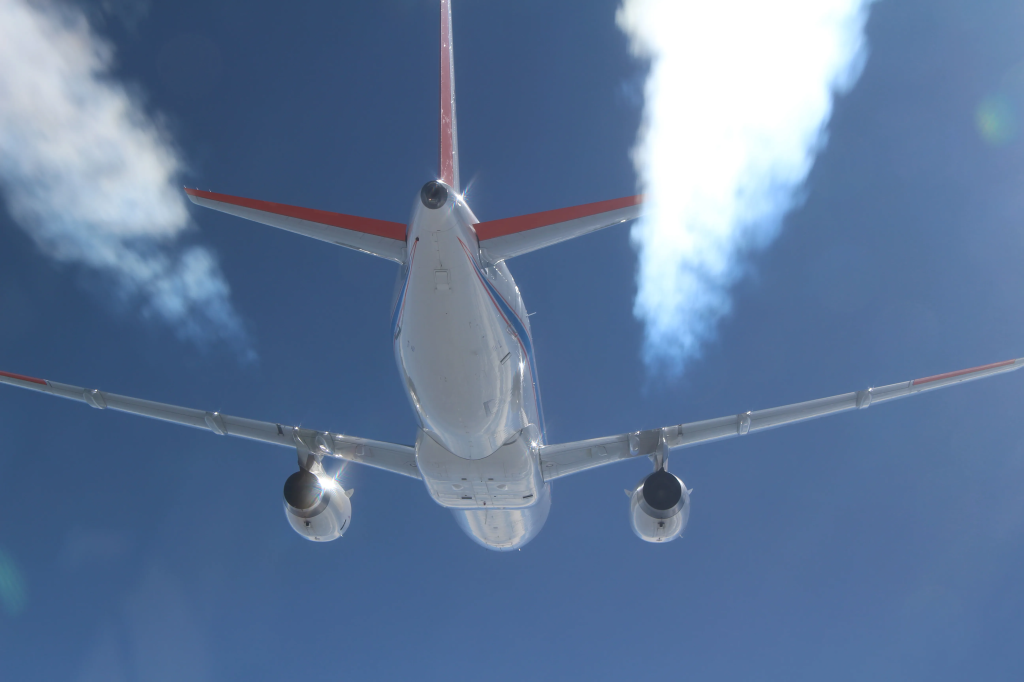

Emissions at 30,000 feet

While we drive a lot less than the average US household, we fly a lot more, though I am pretty sure we are still below average among my academic and professional colleagues. Dividing total US passenger-miles (domestic plus international) by US population works out to about 3000 miles per person per year, or slightly less than one round trip between San Francisco and Houston.

(Source)

We had by far our heaviest travel year since before the pandemic, flying together to Europe, Michigan and Albuquerque, plus my wife took a trip with friends to Mexico City and I had work trips to Boston, Washington DC, and Calgary. In total, it added up to about 50,000 miles of air travel – all purchased before I had written the section of the energy hogs paper on air travel. Using the CO2 intensity numbers from that paper, our air travel amounts to about 8.3 tonnes of GHG, nearly as much as our entire emissions from home energy use and driving. (And it is probably worse than that, because the full impact of emissions from air travel should account for the additional radiative forcing due to high altitude non-CO2 emissions, such as nitrogen oxides, which may increase the climate impact by 90% or more.)

Our 2023 seems like a lot of air travel, and we are very unlikely to match it in the coming years. Still, even our 2023 works out to barely enough to qualify for the lowest frequent flyer status level on most airlines, and only if we were to do all of that travel on a single carrier.

And, unfortunately, low carbon air travel at scale is probably many years off.

What about everything else we consume?

(Source)

Of course, these are just our most direct energy consuming – and greenhouse gas emitting – activities. Overall, they amounted to less than 15% of our total expenditures in 2023. All the other goods and services we bought also created GHGs. Based on some quick calculations of the GHG intensity of everything in the US economy besides residential electricity/natural gas and personal vehicle and air travel, it looks like the emissions from our other expenditures may exceed the GHG emissions of our home and travel energy use. More on that in a future blog post.

What can we do to reduce?

Here’s what I take away from these numbers. California has a pretty darn clean grid, and most of our electricity use is for energy services that we value quite highly, so significant CO2 savings will be tough there.

When it comes to natural gas, we already keep the house at 68° during winter days, turn the heat off at night, avoid long showers, and have wrapped our hot water heater in insulation, so cutting here will also be a challenge. In the next few years, we will probably jump on the heat pump wagon, though the skyrocketing California electricity rates make that a tough choice.

In contrast, our air travel is mostly discretionary and largely recreational consumption. And it is, to me, a shockingly high share of our carbon footprint. Seeing family and friends will still be high priority, but I’m going to think much more carefully about tourist travel and about work trips that aren’t essential, especially when virtual participation is feasible.

We are not a “typical” household

This is our carbon footprint. Your emissions may vary, as they say. In fact, the vast majority of low- and middle-income households in the world don’t have “carbon fat” like discretionary air travel to cut. Reductions from their already-low emissions levels come straight from the meat of their standards of living. It seems only fair for households like ours to move first.

I resolve in 2024 to do less air travel and become more educated about all the ways in which my activities contribute to climate change. But I will not delude myself into thinking that we can save the planet by soliciting voluntary emissions reductions. So I will spend much of my time arguing for better regulation and financial incentives that bend the choices of all consumers towards a sustainable future.

—

I am posting frequently these days on Bluesky @severinborenstein

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Bluesky and LinkedIn.

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin. “Our 2023 Carbon Footprint” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, January 8, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/01/08/our-2023-carbon-footprint/

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

re: “we will probably jump on the heat pump wagon”

Heat Pumps are extremely efficient. I’d encourage anybody to consider switching their gas appliances (furnace and Water Heater) whenever they have an opportunity. Certainly when they need replacing. And keep an eye for new products that are coming to our markets. There are new washer/dryer units that save space and money, and the new ones are fast; and there are new heat pump water heaters that are very quiet and very efficient in energy and space – these products can be game changers and may encourage replacement even ahead of schedules.

In our case we have Rheem HPWH that we installed three years ago. In 2023 it used around 850kWh. Our household is mostly two people with infrequent 2-4 additional visitors; use is mostly showers with occasional baths. Our house is almost 100% electric; we used 38 therms in 2023. Our electric use includes charging 2 EVs at home; I don’t have good numbers for 2023 because our solar panels started producing in August and I didn’t fully instrument the house at that point but in 2022 we used 9777 kWh to charge EVs and run the house.

Seems like the bolts holding the door in place “What about everything else we consume?” sheared off or all of them finally gave way. The bolts were welded tight on the Overton window for rural residents in the state.

Mark

Thanks for the blog. I agree that the focus should first be on ” arguing for better regulation and financial incentives that bend the choices of all consumers towards a sustainable future.” I would add “voting for.” Taking responsibility for how our individual choices impact the climate also seems appropriate. I appreciate that you are conscious of your contribution and thinking about the next action you can take (e.g., insulation and heat pumps, in that order), and buying an EV (or electric bike) as your next vehicle, if any. To meet US Paris targets for 2030, annual reductions in GHG emissions need to decline 6.9% per year from 2024 to 2030.

https://rhg.com/research/us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-2023/?email=467cb6399cb7df64551775e431052b43a775c749&emaila=12a6d4d069cd56cfddaa391c24eb7042&emailb=054528e7403871c79f668e49dd3c44b1ec00c7f611bf9388f76bb2324d6ca5f3&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=01.10.23%20Energy%20%26%20Environment%20JB

You do not have to replace your 2008 Prius (a great car, BTW, we used to have a 2005) with a new EV. You can replace it with a fairly good used EV for less than $10K. Whether it works for you depends on you, and your wife’s, travel patterns. We lived for many years with a 2013 500E and our Prius. It required a bit more logistical effort but it was totally doable.

thank you for this candid and thoughtful summary. I very much appreciated your perspective on “essential” versus “discretionary” energy use, so to speak.

As an ERG graduate and a (now retired) energy economist who lives in Berkeley, I was curious to see how the Borenstein household compared to mine. As it turns out, my wife and I drive less and fly a lot less, but the surprising part was that we also use a lot less natural gas and electricity. We used 3542 kwh last year, versus 5214 (excluding the hot tub, since we don’t have one). We used 466 therms, versus 677. I estimate that our non-furnace gas consumption was 161 therms (based on June-October gas consumption, the months in 2023 when we didn’t run our furnace), more than Severin’s estimated 102 therms (15% of 677). That might be because we have a gas stove (though an electric oven), and we DO take long showers (in lieu of the hot tub, I guess). But if true, that means our gas usage for space heating was only 305 therms, barely half of the 575 therms for the Borenstein’s. What gives? It’s not furnace efficiency – ours turned 31 years old in 2023. It’s not insulation, we have some but not a huge amount, and many of the windows are still single-pane. It’s not the thermostat – ours is typically at 69, albeit with a 10 degree overnight setback. It’s not reduced use due to not being home – I’m retired and am usually home, and my wife works at home. Some internet sleuthing shows that my house is 24% smaller, which explains about half of the difference between 305 therms and 575 therms.

On the electric side, other than the much-loved induction stove, and with the hot tub already excluded from the numbers above, we appear to have similar appliances. Air conditioning would be an obvious explanation – we have none – but Severin writes that they only use theirs a few days per year. Lighting could be an explanation, but only if the Borenstein household has been hoarding 100 watt bulbs from the pre-LED days. Seems unlikely! Square footage explains much of the difference, but not all, and begs the question of why consumption would be proportional to square footage and not to the number of residents.

So in the end, the only explanation I could come up with was location. I live in Berkeley, Severin appears to live east of the hills. Moral: If you want to reduce your Bay Area carbon footprint, move to the west side of the Berkeley/Oakland hills!