The Trouble with Carbon Pricing

It has a face that only economists can love?

We economists have long been enamored with carbon pricing. The concept is simple and sensible. If the economic damages from greenhouse gas emissions can be reflected in market prices, powerful market forces will work for, versus against, the planet.

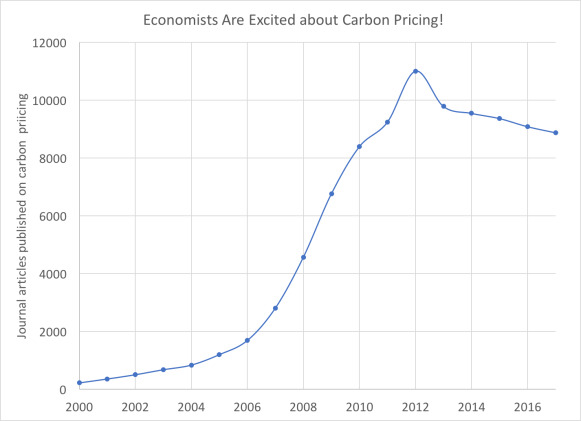

Over the past two decades, a growing number of economists have been working to refine and elaborate on this elegant idea. This chart shows the growing number of papers published on the topic:

Google scholar counts economics papers published on carbon pricing. Numbers were on the rise through 2012. Publications (and enthusiasm) have waned slightly in recent years.

It’s been easy to get economists excited about carbon pricing. But political constraints and widespread public misgivings have greatly complicated the translation from economic journals to real-world policy. Here in the U.S., there have been many failed attempts. And some of the hard-won successes have not endured.

Given this checkered past, and in the light of the new green idealism, many are questioning whether carbon pricing has any place in domestic carbon policy. I think carbon pricing has an essential role to play. But as we economist-types work to define and advocate for this role, we have to accept (versus ignore or wishfully assume away) some inconvenient truths.

Public opinion is shifting…but not fast enough

My former Michigan colleague Barry Rabe and his team have been tracking U.S. public opinion on climate policy since 2008. There’s a lot to unpack in these survey responses. I’ll highlight two key findings here.

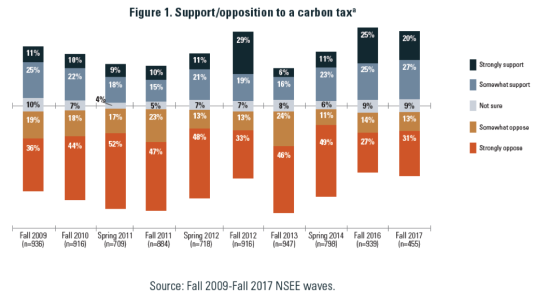

First, carbon pricing consistently finishes last in the most popular climate policy competition. The figure below tracks public support for carbon pricing since 2009. The good news is that, in recent years, supporters are edging out opponents. But the not so good news is that a majority of opponents “strongly oppose” (orange bars) whereas the majority of proponents just “somewhat support” (light blue).

Source: National Survey on Energy and the Environment

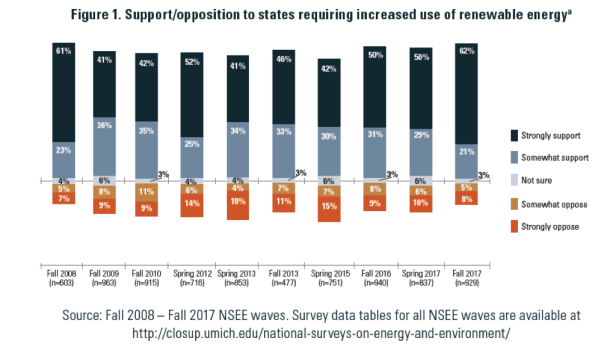

Source: National Survey on Energy and the Environment

The contrast between carbon tax support (above) and support for clean energy requirements (below) is striking. Public support for renewable energy mandates has been strong (deep blue bars) and unwavering. In the most recent 2018 survey (not pictured), a majority (54%) strongly support renewable energy mandates while only 12% strongly oppose. In that same survey, corresponding carbon tax responses are 22% and 30%, respectively.

These voter-on-the-street policy preferences run counter to an economist’s sensibilities. With clean energy mandates, important low-cost abatement potential (such as fuel switching) goes untapped because mandates push clean technology versus penalizing the damages caused by fossil fuels. In other words, reliance on mandates (versus a carbon price) means the (short run) cost of achieving a given level of emissions abatement can be much higher than it needs to be.

Of course, the reality is that asking voters to pay higher energy prices in exchange for some ill-defined promise of future climate benefits is a tough sell. A political advantage of mandates is that they focus on the shiny goal versus the painful process that will get us there.

A second important takeaway is that framing (and revenue allocation) matters. If you ask people whether they support an increase in their energy bills, it’s not surprising that a majority of Americans recoil. But when the tax is tied to more salient benefits (e.g., renewable energy investments), survey responses start to inch closer to the popularity of renewable energy mandates. This is particularly true in recent years:

What if the revenue from the carbon tax was reinvested in renewable energy projects like solar or wind energy? Would you strongly support, somewhat support, somewhat oppose, or strongly oppose such a system?

Source: National Surveys on Energy and the Environment

Americans are willing to pay if focused on benefits versus costs

Survey responses are revealing. But even the most carefully worded survey question about a hypothetical can generate misleading indicators of what people will actually do when it comes time to vote a climate change policy up or down. So it’s worth looking at revealed policy preferences. What are the policies that Americans, or at least their political representatives, have actually been supporting. And at what cost?

The graph below charts the rocky track record of carbon pricing relative to the steady progress of renewable energy mandates in the United States. No state has managed to adopt a carbon tax. But in the mid-2000’s, we saw some exciting green shoots of carbon pricing via cap-and-trade. By 2011, however, more than half the states that had formally signed on to regional initiatives had backed out. In contrast, support for renewable energy mandates endures.

Source: Carbon pricing data taken from Barry Rabe’s excellent book “Can We Price Carbon?” Data on state-level RPS adoption taken from the National Conference of State Legislators.

The carbon prices over this time period were in the range of $2-$3/ton (RGGI) and $12-$15/ton (California). The renewable energy mandates operating over this period were much more expensive. In a backward-looking analysis, we analyzed renewable energy credit (REC) prices paid in 2010-2012, the time when carbon pricing participation was flagging but RPS support was growing. For solar PV investments, REC prices effectively conferred subsidies in the range of $100-$480 per ton of carbon abated. These high – but hidden – costs were being incurred in the same states that were dropping out of – or electing not to participate in – relatively inexpensive carbon pricing programs.

It’s worth noting that these cost comparisons focus on short-run marginal abatement costs and benefits. If we think that renewable energy portfolio standards can more effectively accelerate the large scale innovation and technological change that will be required to combat climate change, then these relative dynamic efficiency advantages would offset some of the additional costs.

Let’s make a green deal

No matter what you think about the Green New Deal, everyone’s talking about it. It points in a radical new direction with few details on how to get there. Discuss!

The GND is intentionally silent on the role of carbon pricing. But if it succeeds in re-energizing the discussion about federal climate change policy (I hope it does) a more pragmatic discussion of the all-important details will ensue. There’s no blueprint for success. But one lesson I think we’ve learned is that a public-facing focus on pricing carbon does not sell well in the mass market. And framing matters. If we lead with the rallying cry of “tax carbon!”, it’s hard to imagine that the politically durable carbon price we could negotiate would be set at a level that is close to commensurate with the climate change threat.

In contrast, Americans in states red and blue have demonstrated a willingness to pay more for green energy if they are focused on goal-setting defined in terms of tangible benefits. Mandates and prescriptive standards are not the most economically efficient solution. But their relative popularity makes them a durable second-best option.

If the public face of domestic climate policy must focus on popular and prescriptive mandates, there are ways to harness market forces in order to lower the costs of delivering on these goals and aspirations. Moreover, if a fraction of the ambition of the GND is retained in future domestic climate policy, we’ll need a way to pay for it. It may pain economists to see carbon pricing cast in a diminished backseat role. But given the political realities, we should work within the constraints these realities impose. And focus more of our energies on designing the best-possible second best.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith. “The Trouble with Carbon Pricing.” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, April 29, 2019, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2019/04/29/the-trouble-with-carbon-pricing/

Categories

50 thoughts on “The Trouble with Carbon Pricing” Leave a comment ›