Three Facts About EVs and Multi-Vehicle Households

Within-household substitution between vehicles could undermine the environmental benefits of EVs.

I got interested in how multi-vehicle households use EVs, because — from a carbon emissions perspective– we care not only about how many EVs are sold, but also about how they are used. After all, it isn’t the manufacturing of EVs that gives them their environmental edge, it’s their potential to offset driving gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles.

The driving behavior of multi-vehicle households is particularly important to understand because these households have so many options with regard to the combination of vehicles they choose to have, as well as the scope for substituting across vehicles when making trips. I’m worried, in particular, that this within-household substitution could undermine the environmental benefits of EVs. This wouldn’t matter in a future scenario with 100% EVs, but it could matter a lot during a long transition period.

So here are some facts based on the 2017 National Highway Transportation Survey. I’ve posted details about all calculations as an Energy Institute working paper here. These are the most recently available nationally representative data. But they are already several years old, and EV market offerings are changing fast, so I will also discuss later how I think these patterns will change over time.

Fact 1: 90% of U.S. households with an EV also have some other vehicle.

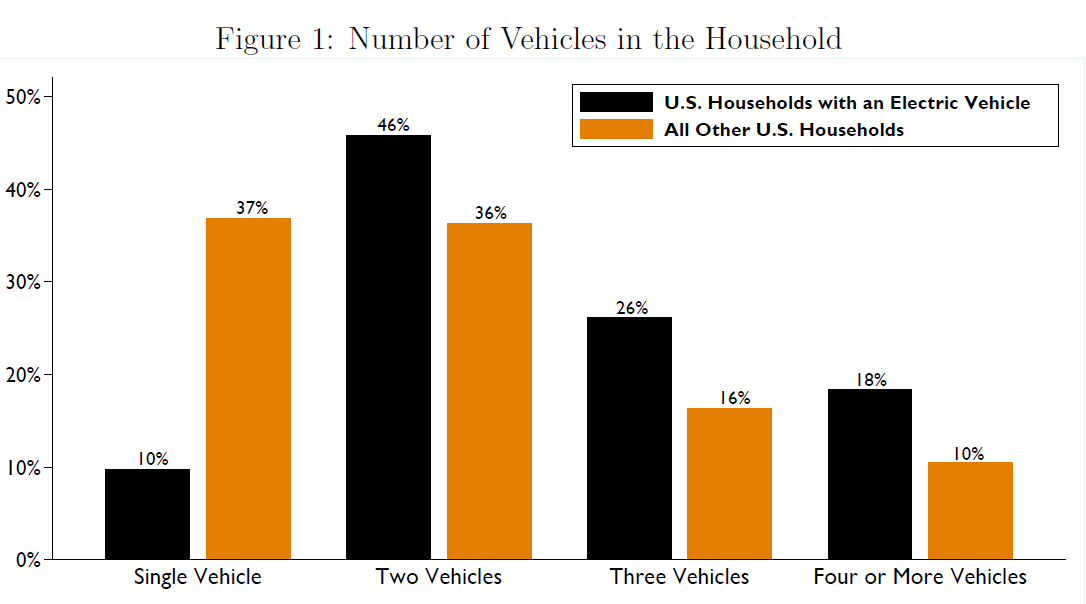

As the figure below illustrates, only 10% of U.S. households with an EV are single-vehicle households. In contrast, 37% of all U.S. households are single-vehicle households. Thus, households with an EV are almost four times less likely to be a single-vehicle household.

In the U.S., it is even common for a household to have more vehicles than drivers. Among U.S. households with an EV, 36% have more vehicles than drivers, compared to 24% for other U.S. households.

This all points to there being considerable scope for within-household substitution. Just because a household has an EV doesn’t mean that will be the vehicle it takes on family vacations, for example.

Fact 2: 60% of U.S. households with an EV also have a non-electric SUV, truck, or minivan.

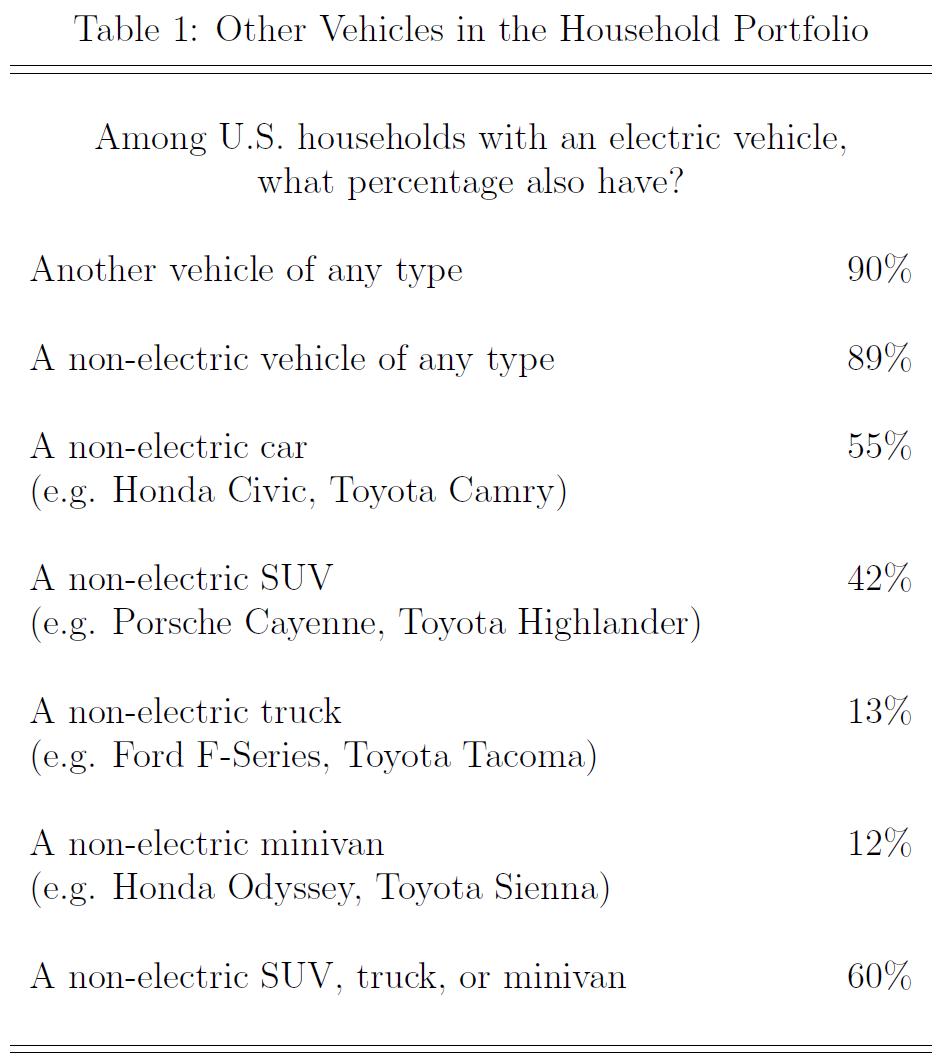

The table below describes the other vehicles in U.S. households with an EV. Cars and SUVs are the most common, but many EV households also have trucks and minivans. Overall, 60% of households with an EV have a “large” non-electric vehicle, i.e., an SUV, a truck, or a minivan.

This pattern makes a lot of sense. These larger vehicles provide differentiation with regard to exterior and interior dimensions, seating capacity, cargo area, and other attributes. In recent research, economists James Archsmith, Ken Gillingham, Chris Knittel, and Dave Rapson find evidence that households substitute between attributes when deciding which vehicle to purchase. For example, a household with one fuel-efficient vehicle may be more likely to purchase a second vehicle that is less fuel-efficient. This substitution between attributes likely plays a particularly important role with EVs, and may help explain why EVs are so popular in multi-vehicle households.

This differentiation is convenient for the household, but it also has implications for fuel economy and gasoline consumption. These larger vehicles in households with EVs have an average fuel economy of 18.8 miles-per-gallon, which is lower than the average fuel economy for the U.S. vehicle stock.

Fact 3: 66% of U.S. households with an EV have a non-electric vehicle that is driven more.

Finally, two-thirds of households with an EV have some other non-electric vehicle that they drive more miles per year. This is somewhat surprising. EVs cost less to drive per mile than gasoline-powered vehicles, so there is a financial incentive for households to use EVs intensively. It isn’t clear why, but there seems to be something about the attributes of EVs that tends to work in the opposite direction.

Regardless of the exact explanation, this substitution of driving toward non-electric vehicles reduces the environmental benefits of EVs and provides additional context for previous studies (here and here) that have tended to find that EVs are driven less than other types of vehicles.

New Generation

This all points to the significance of the newer generation of EVs which include not only cars, but SUVs, trucks, and even this three-wheeled RV. The number of available EV models has expanded considerably and this gives households more flexibility and less need to combine EVs with other non-electric vehicles.

Range is a good example. The earlier EVs had less range than practically any of the models available today. The first generation Nissan Leaf, for example, had a range of less than 80 miles, while the current day Leaf has a 150+ mile range, almost twice the original version.

In the language of a new paper by Stephen Holland, Erin Mansur, and Andrew Yates this means that EVs are becoming closer substitutes to non-electric vehicles, a trend that bodes well for EVs as a climate solution.

Nevertheless, I still think future research needs to think hard about multi-vehicle households. Over the next decade there are going to be millions of households with both an EV and a non-electric vehicle, so we need to understand better both how households decide which vehicles to purchase and how they decide which vehicles to drive.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Three Facts about EVs and Multi-Vehicle Households” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, September 20, 2021, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2021/09/20/three-facts-about-evs-and-multi-vehicle-households/

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

I had a PHEV, which had a bogus electric range of 20miles. Useless for anything other tab a trip to the local grocery store. And the charging rate was atrocious [at 110v]. We just replaced with an ICEngine of the same make/model. Will get a EV for the local trips, and use it ‘most of the time’ locally. The ICE will be for longer freeway travel. Maybe in three years range will have improve enough that we will trade it in

It is significant that you are basing your predictions on pre 2017 data when EVs were short range experiments. It is a whole new ballgame with long range comfortable vehicles like Tesla’s Audi, and Volvo. With fast charging, they will be the preferred means. I am a 1 vehicle, 1 driver family and in almost 3 years gave only needed to rent a truck one time!

I don’t know how prevalent this is, but it wasn’t one of the categories in Table 1 so I thought I’d note it.

As of a week ago, we traded in our last ICE vehicle in our two car household. We now have a Tesla 3 and a Nissan LEAF SV Plus.

I agree completely with many of the comments already submitted. While the subject matter studied here is important, the research needs to go further than taking a single snap shot of data that is over 4 years old and drawing such strong conclusions from it. The EV market is changing rapidly and no single snapshot of the past can tell us much about what the future will look like.

Some suggested further research avenues: Using the existing data look at how EV usage patterns match up with utility factors (UF) for electric vehicles with ranges typical of the EV fleet in 2017. How does that driving behavior match with what would be expected based on the UF? Similarly look at the other vehicles in the households with EVs and compare their driving behavior with similar vehicles in households without EVs (are they driven more or less?). Looking at future changes in range and fleet mix (reasonable projections could be made based on automaker announcements and various EV market projections) how does what was learned from the past inform how you would expect EV utilization to change into the future as the fleet evolves and infrastructure is expanded?

I’m sure there are plenty of other ways to get at some of these questions and I urge the authors to think deeper and try to find ways to expand their research in ways that make their conclusions useful beyond being able to say what things looked like in the past when the EV fleet was completely different than it is today, and will be in the future.

How about demanding EV manufacturers disclose summaries or snapshots of the reams of data they collect on the driving behaviors and habits of owners of their vehicles?

My family’s experience with an EV suggest Jim Lazar’s assessment holds water. We have a Nissan Leaf and a Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid. We always choose the Leaf first for any in-town driving, but we also take a road trip every year and visit family across the state, trips that we simply can’t use the EV for. Those long-distance miles add up quickly.

Even a midrange EV will change the calculus for us. Frequently visited family lives about 200 miles away. Once we have an EV that goes that distance, it will significant cut down the gas-driven miles.

We have easily done a roundtrip of 330 miles (Westwood, MA to Ithaca, NY) with a Tesla having a nameplate range of 220 miles, with no inconvenience for charging stops. With that, and our new 2022 Nissan LEAF SV Plus, we have no concerns whatsoever about ranging that far, or farther, even if we need to leave the vehicle parked with cooling operating on hot summer days.

This is a new technology. They can’t be driven in the same manner, style, and rules that ICE vehicles are. That mostly means the routes need to be planned. But what that also means is that hops of 100 miles one way don’t need to be planned at all.