It’s Climate Change, Stupid

Let’s get the electricity sector ready for a world with a very different climate.

My phone has been ringing off the hook this week. Well, my phone does not have a hook, but I’ve been busy. Why? Because California is literally on fire, in the middle of a historic heatwave, during an epidemic, two months before an election that will decide the future of… oh well…. so much! The question I am being asked over and over is, “Does this have anything to do with climate change?” The answer is: Ja. Si. Yes. Zee ha’a. Kyllä. Ken. Vâng. So let me spell this out for you and then focus on what this means for the energy sector, and maybe most importantly what we should do about it.

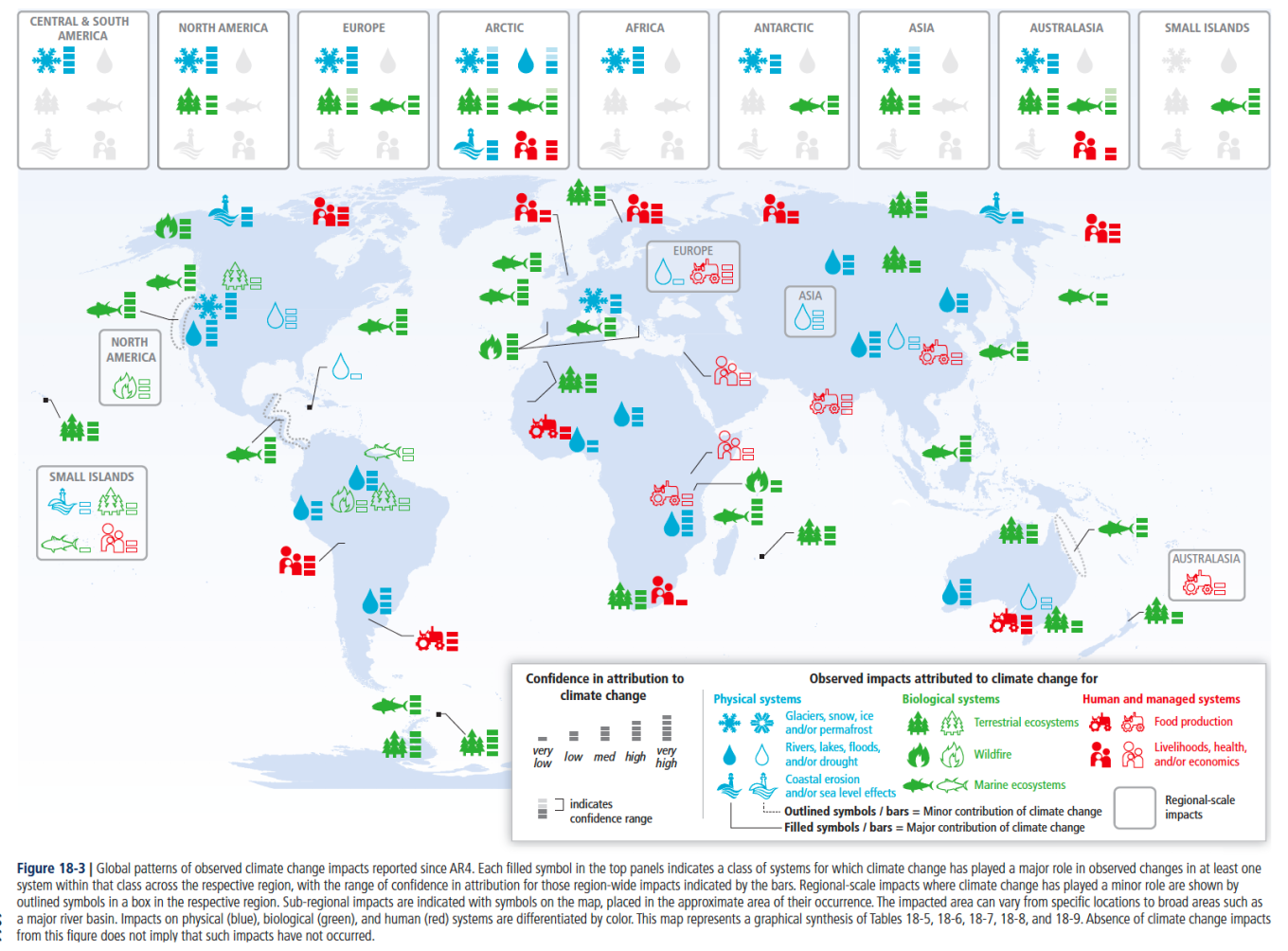

Climate change is here and has left its fingerprints all over the place. I helped write a chapter on this for the IPCC’s last assessment report. We showed that you can detect and measure impacts of warming and sea level rise across the globe by reading close to 1,000 papers. It was super fun. If you’d like a map, here you go.

If you’re not convinced and think we’re just a bunch of leftist hippies spouting nonsense, I invite you to visit the Berkeley Earth Project’s site, led by a former climate skeptic, showing that it’s gotten warmer pretty much everywhere and that there really is no other factor that can explain this warming other than anthropogenic emissions. The science on attribution is advancing rapidly. If you’re interested, I would suggest checking out Noah Diffenbaugh’s work at that other school around here.

One of the big questions on everybody’s mind right now is whether climate change leads to an exacerbation of wildfire conditions on the west coast. Well, here’s some new science for you. If you run some fancy climate models with and without additional human made greenhouse gases in them, you can calculate what climate would have been like in the absence of that climate change. And the news is not good. They find that “the observed frequency of autumn days with extreme […] fire weather—which we show are preferentially associated with extreme autumn wildfires—has more than doubled in California since the early 1980s” and climate change has increased the probability of this extreme weather. To translate. Climate change is not the match that lights the fires, but it’s the equivalent of pouring gasoline on kindling to make it really go. So while we’re all mad that PG&E and that gender reveal party lit some of the major fires, there is another actor here.

So what does this new normal mean for the electricity sector? It’s like the old testament. Heat, Floods and Fire!

Heat

1) Demand goes up! When LA’s future summers will look like the three hottest days of the 1980s and San Francisco’s climate looks like Fresno’s, demand goes up. The grid will of course need to be built for those days (in theory). So if peak demand goes up, we need more peaker capacity. And make sure we calculate those reserve margins appropriately, CPUC.

2) Transmission capacity goes down. Hot wires are worse at shipping electrons around. So when demand is already high, the wires that get the electricity to your home and company are “smaller”.

3) Generation is less efficient. When it’s hot outside, certain power plants become slightly less efficient. This means for each therm of gas going in, you get less power coming out. And generators are more likely to conk out completely in extreme heat, when you need them most.

Flood

1) Energy infrastructure is at risk. When you add three feet of sea level, and a storm on top, lots of areas that were previously safe from so-called 100-year floods (a flood that has a 1% chance of occurring in a given year) no longer are. For the electricity sector this means that power plants, substations and transmission infrastructure that are built already, or will be built, need to take this new normal into account.

Fire

1) Transmission infrastructure is at risk. When there are fires, transmission infrastructure can become less efficient due to the heat from the fires or deposition of ash on wires. Or if a fire directly threatens major transmission lines, these may have to be shut down and may negatively affect big demand areas, like LA and the Bay Area.

2) Generation infrastructure is at risk. Plants in areas affected by fires are at risk – just like any other fixed asset.

3) Dimming affects renewable production. If, like it did last week, smoke from fires lead to large reductions in sunlight reaching solar generators, generation might decrease. While many of us noticed a large reduction in generation from our rooftop solar, utility scale solar was largely unaffected due to its location far away from the fires.

So are all of these equally important? No. It’s the impact on demand that matters most. As my friend Severin, who sits on CAISO’s board, will tell you all day long, meeting demand on hot days is the hard part. Especially when it’s hot outside across the West and it’s harder for California to import electrons from Nevada, Arizona, Oregon and Washington.

What should we do?

I think there are a few immediate things regulators can take into account.

1) Listen to science and figure out how climate change is going to affect peak demand in California and in our neighboring states in a world with a changed climate. The California Energy Commission only started doing this somewhat crudely two years ago. This is going to require more science and modelling and I am excited to see that the CEC is funding some projects on this topic (I am not on any of them, so this flattery is sincere).

2) After listening to that science, plan accordingly and revisit reserve margin requirements to make sure there is adequate capacity available.

3) Aggressively push innovative proposals such as those proposed by Meredith, Duncan and Severin last week to manage demand when supply is short.

4) When planning for new energy infrastructure investments, proposals should have to include planning for the life of the gadget – taking into account the changing climate impacts at that location. This is not hard, but should be required.

5) Manage the matches. We are not going to stop climate change. We need to continue aggressive efforts to reduce the risk of energy infrastructure setting off fires. That will be expensive.

So if you read this far, thank you. These are scary times. Let’s continue working on cost-effective solutions to this long-run problem. There is lots to do!

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Auffhammer, Maximilian. “It’s Climate Change, Stupid” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, September 14, 2020, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2020/09/14/its-climate-change-stupid/

Categories

Maximilian Auffhammer View All

Maximilian Auffhammer is the George Pardee Professor of International Sustainable Development at the University of California Berkeley. His fields of expertise are environmental and energy economics, with a specific focus on the impacts and regulation of climate change and air pollution.

“I invite you to visit the Berkeley Earth Project’s site, led by a former climate skeptic, showing that it’s gotten warmer pretty much everywhere and that there really is no other factor that can explain this warming other than anthropogenic emissions.”

Then the Berkeley Earth Project’s site is showing what climate scientist James Hansen explained to a Senate committee 32 years ago.

“it [NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies] was 99 percent certain that the warming trend was not a natural variation but was caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide and other artificial gases in the atmosphere.”

“What should we do? I think there are a few immediate things regulators can take into account. 1) Listen to science and figure out how climate change is going to affect peak demand in California and in our neighboring states in a world with a changed climate.'”

Which is a more reprehensible response to climate change: 1) denial, or 2) mitigation? I vote for the lazy, self-serving myth humans can adapt to a world that’s 37ºF warmer than it is now; that meeting peak demand might take priority over extinction of 90% of Earth’s species.

The most obvious thing California regulators can take into account now is preventing the premature shutdown of Diablo Canyon Power Plant, and preventing 9 million more tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere each year. After all, it was James Hansen who, in 2015, announced to attendees of the COP21 Climate Summit that “nuclear power paves the only viable path forward on climate change.” If we’re forced to wait until 2047 for Hansen to be proven right – again – at least California regulators of the future will get a measure of what they deserve.

Carl

I agree with your general sentiment, but then you turn to a trivial solution to the problem that is no better than focusing on peak demand needs. Your calculation of additional emissions from Diablo represents about 2 percent of California’s GHG emissions: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/ghg-inventory-data

Further is makes the rather naive assumption that Diablo generation will be replaced with purchases from the CAISO at the allowable emission rate under state law. First, the incremental heat rate on the CAISO implies that its 7.4M tons. But even then, the majority of resources replacing Diablo with be zero emission renewables and energy efficiency. The renewables will be able to fill the generation space cleared by the retirement of Diablo.

Instead of focusing on a rather trivial, and dead end, resource in the scheme of reducing GHG emissions, we should be focusing on the much larger scale reductions available from electrifying buildings and transportation and adding renewables, both utility scale and distributed to power those. Fighting over Diablo Canyon is a distraction.

“Your calculation of additional emissions from Diablo represents about 2 percent of California’s GHG emissions.”

Why are you including emissions from transportation? The shutdown of San Onofre increased California’s in-state electricity GHG emissions by 24% – not including methane leaked from Aliso Canyon, as a direct result of the shutdown of SONGS. That nullifed the entire carbon-free contribution of California renewables for the year 2015 – not trivial at all.

“But even then, the majority of resources replacing Diablo with [will] be zero emission renewables and energy efficiency.”

Why do excuses for the poor performance of renewables always slip into future tense? We were promised SONGS would be replaced by renewables, too, but a post-mortem showed they replaced less than 1%. The other 99%+ was replaced by gas and “Unspecified Sources of Power”, a category invented in AB 162 (2009) to help export California emissions to Wyoming. And though it may be a common meme among physics-challenged wind/solar advocates, efficiency can’t serve as a replacement for energy any more than bananas can.

It’s amusing, and actually encouraging, to hear antinuclear advocates declaring nuclear to be a “dead-end” resource. In truth, U.S. nuclear is generating more carbon-free energy each year than it has in the last ten years, and twice as much as wind and solar combined. Unlike intermittent renewables, nuclear actually improves with age. Which is the dead end, again?

While I agree that human cause climate change is real, the Antiplanner just posted stated posting that the forest fires we are seeing are not unusual over the last few thousand years, see:

https://ti.org/antiplanner/?p=17599

It does seem reasonable to look at the fire record over hundreds if not thousands of years rather than since 1980.

However, this still means we should be fire hardening properties and reducing carbon dioxide production. We should support the most cost effective method of carbon dioxide production such as the fee and dividend endorsed by thousands of economists, see:

https://clcouncil.org/economists-statement/

The Antiplanner has at least two errors. First, I’m working on a project using a paleohistory of hydrologic conditions. The drought of 2012-2016 compares to the drought from 1,000 years ago. This was not a typical event–it was an outlier.

Second, he looks at 2020 in isolation and California (or maybe the West Coast) isolation. It is the increased prevalence of wildfire in Australia, the Amazon, Southern and Northern Europe and Siberia that is part of a larger pattern. Each of these in isolation may not look like they are climate related and somehow explained by local factors, but the simultaneous confluence points to a more common cause.

Dear Max,

Thanks for your deep dive into wildfire science and climate change and thanks for keeping a sense of humor during these strange days.

So I”m grey-haired enough to remember the rolling blackouts from 20 years ago and the lovely candlelight dinners my family and I shared. Those rolling blackouts were like clockwork, literally! Power off at 7:00 pm, back on at 8:00 PM. That was a different time (although climate change was well known) and the root cause of the rolling blackouts was nefarious high jinks by Enron.

“Intermittent” Renewable energy appears NOT to have been the culprit for the relatively small amount of rolling blackouts we experienced in August, although you sure might believe otherwise given the noise from the clean energy haters. Tripping natural gas plants, a major transmission line outage, and lack of availability of imported energy were the bad actors. (The tripping natural gas plants are particularly ironic (comical?) given FERC’s 2018-2019 attempts to claim that coal and natural gas power plants were more resilient than other power sources and thus deserving of financial support.)

Your proposed antidotes to having an electricity grid designed to take on the climate change ravaged 21st century are admirable Unfortunately, “listening to science”, the most straightforward, has become ridiculously politicized and may be the most challenging. .The electricity grid that we have is certainly not the one we want, and I’m also not convinced that the utility business model we have in California is the one we want. Leaving fossil fuels in the ground and focusing our efforts on decarbonization and climate change mitigation seems a clear-cut strategy in these smoky and scary times.

Thanks for your insights!

.

‘It’s more than Climate Change, Stupid’:

https://www.nationalreview.com/the-morning-jolt/california-burning/

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2020/09/14/gavin-newsoms-exceedingly-ignorant-climate-claim/?fbclid=IwAR15sSZE6XPPj3YJkT0-HlBKFxMXt5l5_074qBWlhM8X6O1xgC_tDNw3uM8

This analysis is so simplistic as to be laughable. Here’s a lay summary of the research that contradicts this with rigorous analyses: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/09/climate-change-increases-risk-fires-western-us/#close