Should California Keep Its Oil in the Ground?

The direct costs would be large. The enrichment of world oil producers would be even larger.

A few weeks ago, when California happily announced that it had met its 2020 goals for GHG reductions four years ahead of schedule, there was a disappointing part of the story that didn’t get much attention: transportation emissions. While California has made significant strides in renewable electricity generation and building energy efficiency, emissions from cars, trucks, and airplanes have been rising by about 1.5% per year since 2012.

One policy response that has emerged — and got a boost earlier this year from a report out of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) — is to curtail oil production within California. Versions of this proposal range from banning new drilling to gradually phasing out all oil production in California.

California produces less than 0.5% of the global oil supply, so you might ask what this has to do with reducing California transportation emissions. The SEI report makes clear that the connection is indirect: cutting California oil production would slightly reduce world oil supply, which would slightly increase the world price of oil. Sure, the price effect would be small, but it would apply to the entire world market — not just California’s 1.7% share of consumption – so it might noticeably reduce oil consumption and the associated greenhouse gases.

Some have argued that this wouldn’t work, because California’s reduced output would just be replaced by output from another oil producer. But energy economists recognize that’s not entirely true. The replacement ratio is almost certainly less than one-for-one, because price would have to rise at least a little to elicit additional supply and that price increase would lead to at least some reduction in demand from consumers. How much of California’s production curtailment would show up as reduced worldwide oil consumption? Well that depends on some pretty geeky arguments about how much price would need to increase in order to bring forth new supply and how responsive to such price increases consumers would be.

SEI makes a range of assumptions about these factors and ends up concluding that for every barrel of oil that California leaves in the ground, world consumption would drop by somewhere between 0.2 and 0.6 barrels. If that sounds like a wide range of uncertainty, it’s because it is very difficult to know what technologies oil producers will be using 5, 10 or 30 years from now, or what alternatives to oil consumers will have in the future.

Still, even accepting SEI’s numbers, the policy raises some serious concerns.

The Big Cost to California Oil Producers

First, there would be real economic costs to curtailing California production. SEI recognizes that one major cost would be the lost income to the state’s oil producers. The report divides these lost profits by the estimated worldwide GHG emissions reductions to come up with an estimate for one Southern California oil field in the range of $110-$330 per ton of emissions saved. One can quibble with some of their assumptions — the oil price forecasts they use is likely too high, which would make the policy look more expensive, while the field they highlight is more costly than most California oil, which lowers lost profits and makes the policy look less expensive — but this is not an unreasonable first-cut cost estimate for the policy.

If you follow debates over GHG reduction policies, these look like very costly reductions. For instance, the most recent estimates of the social cost of carbon (SCC) — which is supposed to represent the incremental climate change damages from releasing one more ton of GHGs today – are in the $40-$50 range. It looks like the costs would greatly exceed the benefits.

Advocates of this policy note that the cost-effectiveness range for keeping oil in the ground is not that different from estimates of the cost per ton of GHG reduction from California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard or from some of the more early-stage technologies for generating carbon-free electricity. I’m not a fan of the LCFS, but in any case there is a big difference: those policies are also intended to create new knowledge through R&D and development of new technologies. Sure, raising the world price of oil indirectly incentivizes work on alternatives somewhat, but it is a much more roundabout route.

The Bigger Cost to Oil Consumers Everywhere

More importantly, there is a second cost that SEI and the advocates of this policy have not incorporated: the massive transfer of wealth from consumers to producers that would occur from such a policy. Remember, the way that this policy reduces emissions is by raising the price of oil, which means all consumers pay more and all producers (except for those curtailed in California) make more money. SEI calculated only the direct economic cost to California oil drillers per ton of GHG abatement. In a similar way, one can calculate how much more consumers worldwide would pay to producers compared to the amount of GHG abated.

The details of this calculation are not that complicated, but probably not blog-appropriate. You can find them here. What they show — using the middle of the range of assumptions that SEI made – is that if the policy were to reduce California’s production by, for example, 100,000 barrels per day (about 20%), it would raise the $70ish per barrel world oil price, by about 8 cents.

Carrying that increase through to higher consumer payments for gasoline and other refined oil products, and then dividing by the reduced GHG emissions that the higher price would cause, it means consumers would be paying an additional $510 to producers for each ton of GHG emissions saved. That is, every ton of GHG abatement brought about by this policy would cause not just an economic loss to California producers of $110-$330, but also an additional payment of $510 from the world’s oil consumers to the world’s oil producers, nearly all of whom are outside California.

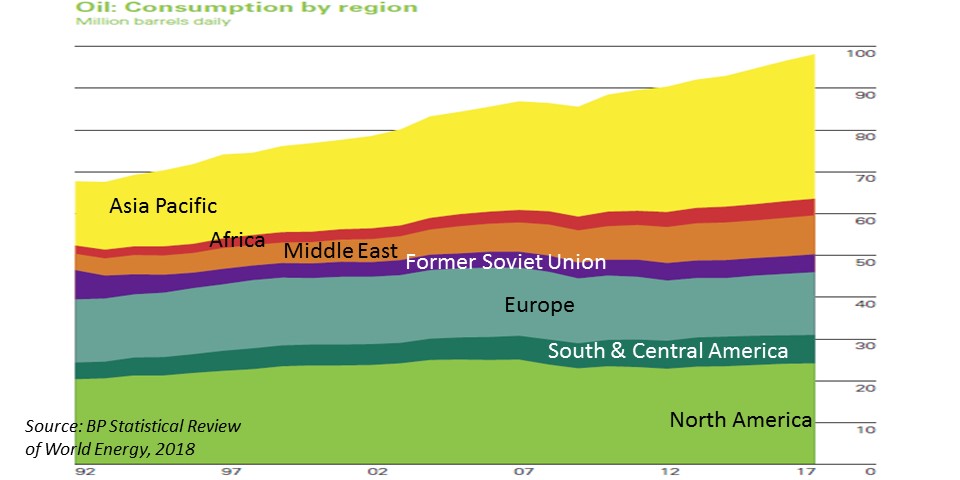

One could think of this as similar to a very small worldwide carbon tax, except in this case the revenue is not rebated to the population as a whole or used to reduce other taxes, but rather handed to those who own and control the world’s oil production. Where are those producers who would get this windfall?

The figure above shows where current oil production come from. Total oil reserves are even more tilted towards OPEC. Either way, this is not a wealth transfer that’s easy to get behind. Most of the world’s oil in the next few decades is likely to come from autocratic regimes, with much of the incremental profits going to a small group of a wealthy oligarchs, officials, royalty and other insiders. Those additional payments would come from people across the income spectrum, including billions of individuals in developing countries (think China, India and much of Africa) where vehicle ownership is just beginning to take off.

Setting an Example for the World’s Oil Producers?

Proponents of keeping California’s oil in the ground argue that not only would the policy have the direct impact of reducing GHGs, but it would also demonstrate leadership for a policy that could spread across oil-producing regions. Really? Take another look at that breakdown of oil supply. I don’t see many big-slice countries that are likely to follow California down this path.

With the daily reminders that our federal government is now determined to pursue a head-in-the-sand climate strategy, it is certainly important to think broadly and creatively about ways in which sub-national entities can help move the needle. But it is also important to think through all of the ramifications. When I consider the full picture on keeping California’s oil in the ground, this does not look like one of our better options.

Instead of taxing the world’s oil consumers to hand that money to a small group of rich and largely anti-democratic leaders, California should be focused on developing alternatives that make it easier for consumers to break their addiction. A good place to start would be with California’s own growing addiction.

[Final Note: I realize that there are other reasons put forth for curtailing California oil production, such as reducing the local pollution associated with that production, an issue I have addressed with respect to oil refining in another blog. This blog is already too long, and the primary argument of the keep-it-in-the-ground proponents is reducing GHGs.]

I’m still tweeting energy news stories/research/blogs most days @BorensteinS

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Thanks for the careful look into our paper, Severin, and considering the potential wealth transfer is valid. In your closing paragraph, you frame the choice for California as either reducing oil demand or supply. I think your points about the wealth transfer might look a little different if one considered demand and supply policies in tandem. From that perspective, a limit on supply could be viewed as making sure that the rest of the world doesn’t end up consuming the oil that California no longer burns due to its impressive reductions in demand (due to, say, EVs). Reducing supply would therefore seem to fulfill ARB’s mandate to consider emissions leakage, and essentially mean there is no wealth transfer.

Its not Californias oil. It belongs to the people who own the mineral rights. So are you planning on stealing those rights? In any case it is just virtue signalling. Nothing Californai can do will make any difference becasue China and India will not sacrifice the wellbeing of their people to a computer generated fantasy. We should be focused on our homless and decaying infrastructure not on some pie inthe sky fantasy.

This weekend’s NYT Mag piece “Losing Earth” should give us pause here. Let’s try an optimistic assumption. Suppose California turns the corner and manages to go down the path of reduced consumption of petroleum products: 1. should California’s petroleum industry be permitted to maintain output and increase exports, or 2. should a policy path be adopted to wind down production? If the latter, what measures would you recommend? There will be costs in either case. Who should pay?

Obviously a good excuse to raise gasoline taxes as they will reduce consumption and generate local revenues!

Thank you. The “leadership” argument assumes that reaction functions are positively sloped. Standard economics has it the other way around. As Elinor Ostrom said, “nobody likes to be a sucker” (by providing more of a public good w/o an agreement from other parties to do likewise). But California may be an exception to Ostrom’s Rule.

And even if leadership selectively works (e.g. in a few Progressive governments like Hawaii’s), that may only trigger a green paradox (get it while the getting’s good).

Finally, there is no guarantee that a ban would be honored by future California governments.

Thanks for a terrific post! The idea of California inspiring others to stop producing oil is especially hilarious. But these arguments keep coming forward.

To Severin Borenstein/View from Canada : Not long ago “peak oil” and “continental energy security” were primary concerns. Being good neighbours and partners ( including NORAD ) we’ve invested hundreds of billions of dollars developing our oils sands ( 300 billion barrels at today’s prices ) which are supplying the giant refining complexes on the Gulf of Mexico coast ( originally designed to handle crude from Venezuela-before that country imploded ). We’re as committed as anyone to controlling climate change, but gradually. In Alberta, we have a social democrat government that is actually leading Canada. Severin – Haas Alumni Office wants me to meet you. I live in Calgary but am in Berkeley frequently. I’d like bring our Premier Rachel Notley to speak there. Russell Kalmacoff HaasMBA, Founder UCB Alumni Club of Canada, Campaign Chair for Professor of Cdn Studies, Advisory Board of Clausen Center. Call me any time 403-6139336.

The researchers at SEI do not seem familiar with the petroleum constraints faced by California. They are so focused on GHG reducing emissions that they do not consider the second-order environmental impacts of their “keep-it-in-the-ground” policy recommendation. Could someone send these Seattle-based researchers a DVD of “Free Willy 2” to remind them that the risk of oil spills matter and that by accelerating the increase of water-borne petroleum imports and marine traffic increases the risk of such man-made environmental disasters?

The first question that comes to mind is “Why California?” Seems to me the Stockholm Environmental Institute should have looked in its own backyard. Curtailing North Sea oil production would have a similar effect.

I think Californian’s are already bearing a disproportionate share of the cost of combating global warming. Enough is enough! A more rational strategy would be to impose strict limits on fracking in the US, primarily through regulations to control fugitive methane emissions. Also, that would distribute the cost over a number of (mostly Red) states.

I fully agree with Severin.