Air Pollution Inside Baseball

What major league baseball can and cannot teach us about air pollution impacts.

I am not a follower of major league baseball. I can’t tell you who’s up this season. I don’t know an ERA from an RBI. But this new paper, which takes a deep dive into baseball “sabermetrics”, has piqued my interest in the sport. Turns out, America’s favorite pastime has something to teach us about America’s most important environmental health risk: air pollution.

If you are a follower of air pollution research, you know that air pollution has been linked to a long list of bad outcomes (e.g. premature mortality and dementia). You may also know these studies can be controversial. One reason is that it can be difficult to definitively establish a causal relationship. For example, if people living in areas with bad air quality are also exposed to more than their fair share of other stressors (such as poverty or limited healthcare), we risk confusing the effects of air pollution with other drivers.

A related issue is that researchers often use private data on individuals’ health outcomes and medical histories to help disentangle the effects of air pollution from other factors. A troubling debate is brewing over how research using confidential data, dubbed “secret science” by the recently departed EPA administrator, can be used to inform air pollution standards and regulations.

What does any of this have to do with baseball? Every so often, clever researchers spot the research design equivalent of a four-leaf clover. A situation where variation in pollution exposure is as-good-as randomly assigned, and all the data needed to test for causal impacts are out there in the wide-public-open. One of these rare opportunities has recently been found in major league baseball by economists (and baseball fans) James Archsmith, Anthony Heyes, and Soodeh Saberian.

Bad Calls on Air Pollution?

To understand what this paper is doing, you need to know something about major league umpires. I have recently learned that umpires work 142 games during a typical season. The umpire behind home plate makes about 140 split-second calls between a ball and a strike per game.

This is a high-stress, high-stakes job. It requires skill and effort and sustained concentration. And thick skin given the vitriol of baseball enthusiasts contesting bad calls.

As for research enthusiasts, this provides a terrific setting for assessing how short-term exposure to air pollution affects work performance and cognitive ability. There are at least four reasons I can get excited about this research set-up:

- Pollution exposure varies across games: Air pollution levels vary significantly across time and across baseball stadium locations. This allows researchers to observe umpires performing the same stressful task under very different air quality conditions.

- Random assignment of umpires to game locations!: Where a given umpire is working on a given day is determined before the season starts using an optimization algorithm that rotates umpires across 30 different stadiums (subject to cost and logistics constraints). Upshot is that umpires are as good as randomly assigned to stadiums – and air pollution levels.

- Detailed measures of job performance: Since 2008, MLB ballparks have used high-precision pitch-tracking technology called PITCHf/x to objectively assess umpire performance. Pitch-by-pitch data track every ball thrown and ever call made by every MLB umpire since 2008. That’s a lot of balls and strikes!

- Public data!: If you are an econometrician interested in assessing air pollution impacts, you can download air pollution monitor data from hundreds of active PM2.5 monitors around the country. If you are a sabermatrician interested in umpire performance, you can download PITCHf/x data.

Screen capture of an MLB game taken from Archsmith et al. (2018). The graphic uses the PITCHf/x data to show the locations of all pitches thrown during this at-bat relative to the strike zone.

To sum up, these authors use publicly available data to estimate a causal relationship between air pollution exposure and umpire performance (measured as the share of umpire calls that agree with the computer-based assessment). After controlling for all sorts of factors that could affect an umpire’s judgement (such as venue, day-of-week, temperature, humidity, wind speed, pitch break angle, pitch type, etc.), they find a significant relationship between air pollution and on-the-job error rates:

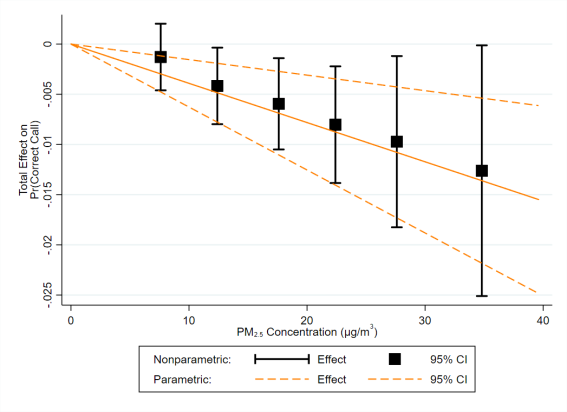

Figure 4 in the paper plots the comparison of estimated effects of PM2.5 on the probability the umpire makes a correct decision.

Figure 4 in the paper plots the comparison of estimated effects of PM2.5 on the probability the umpire makes a correct decision.

These estimates are somewhat noisy. But they imply that a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations causes an extra 0.4 incorrect calls per 100. These negative effects show up well below the current national 24hr standard of 35 μg/m3. If you’re curious about where you sit on this concentration continuum, use this map to estimate PM2.5 exposure in your location (thank you Berkeley Earth!).

Any baseball fan will tell you that what happens on the baseball field is just a reflection of society. Umpires are not the only ones who need cognitive effort and sensory attention to do their jobs well. If we extend results from this study beyond the baseball field, the productivity and human capital costs of air pollution exposure could be far-reaching.

The Inside Baseball of Air Pollution

When policymakers set air pollution standards, they’re typically more focused on first-order health impacts versus impacts on job performance. Unlike data on umpire calls, however, data on individuals’ health outcomes and medical history are private. The most rigorous research on health impacts uses confidential data to isolate the effects of air pollution on health. Indirectly, we have these health-based studies to thank for past, policy-induced improvements in U.S. air quality.

However, a recently proposed rule could significantly limit the types of research that the EPA can use when it develops emissions standards and regulations. This may seem like obscure inside-EPA-baseball. But it’s important:

“The proposed regulation provides that, for the science pivotal to its significant regulatory actions, EPA will ensure that the data and models underlying the science is publicly available in a manner sufficient for validation and analysis.”

On the face of it, it’s hard to argue with principles of transparency and reproducibility. But the language of the rule is vague and concerning. Taken to an extreme, the baseball study clears the bar, but essential research that uses data protected under confidentiality agreements to document health impacts would be disbarred, even if researchers provide detailed code and documentation. We can’t make good, evidenced-based policy if some of the best evidence is locked out.

As the editors of leading scientific journals explain in this letter, there are smarter ways to balance the need for transparency and the obligation to base regulations on the best available science. When baseball fans see a bad call, they argue against it and agitate for better. This clean air fan will be arguing against the “transparency rule” as written. The deadline for public comments has been extended through August 5.

Categories

PM2.5 has a long term effect on health. Ozone has a more immediate acute effect. It would be interesting to see the same analysis with Ozone. There is a significant correlation between the two (PM2.5 formed from reactions of smaller particles and gases catalyzed by Ozone), but I would expect ozone to have a stronger correlation to more bad calls than PM2.5.

I always suspected that the Dodgers got screwed by the blue.