Clean Energy Tax Credit Concerns

Credits for heat pumps, EVs and solar panels still go mostly to the wealthy.

Over the last two decades, U.S. households have received $47 billion in federal income tax credits for buying heat pumps, solar panels, electric vehicles and other clean energy technologies.

In a new Energy Institute working paper, Severin Borenstein and I use tax return data from the IRS to examine which households get these credits and how that has changed over time.

We studied these questions about a decade ago, but we think now is an opportune time to revisit the topic. Last year was the warmest year on record, and rising temperatures and other climate impacts are spurring policymakers to introduce and expand subsidies like these to help transition markets away from fossil fuels.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, the tax credit for heat pumps increased last year from $300 to $2000. The IRA is interesting also because it includes maximum income limits and other features designed to change who is eligible for these credits. Our data cover 2006-2021 so we are not yet able to look directly at the IRA, but we can shed light on the period leading up to it.

—

High-Income Filers

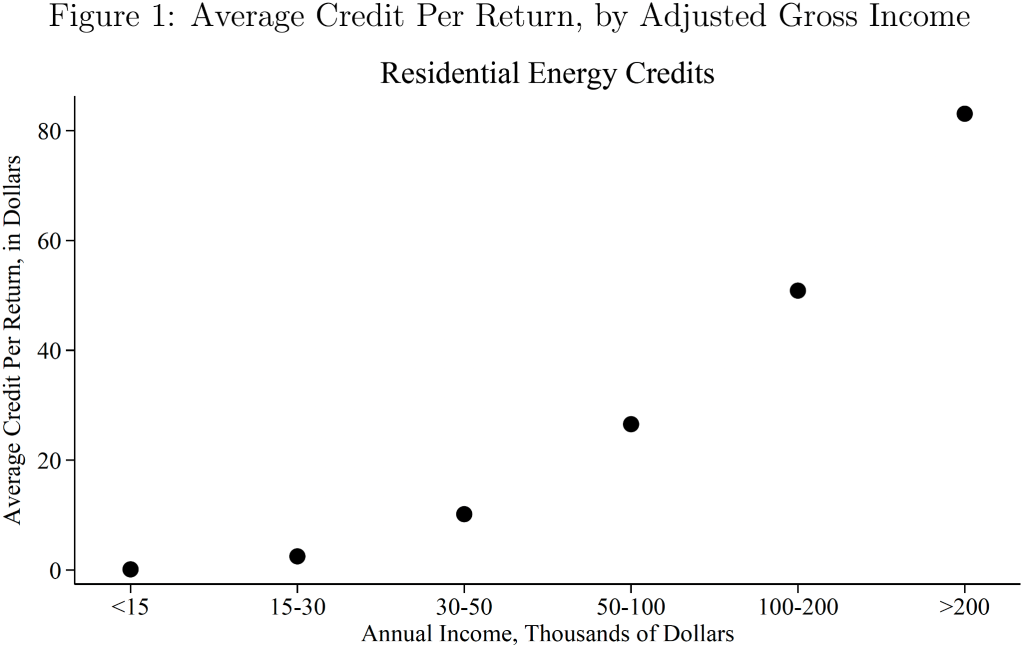

We find that clean energy tax credits have gone predominantly to higher-income filers. The figure below divides filers into six categories based on their adjusted gross income. The first four categories are approximately quintiles and then the last two categories together make up the top quintile.

—

For a broad set of residential energy tax credits, the bottom three income quintiles received 10% of all credits while the top quintile received 60%. The figure above reflects the entire time period 2006-2021 and includes two major categories of tax credits: (1) energy efficiency investments including , for example, windows, doors, and heat pumps, and (2) residential solar.

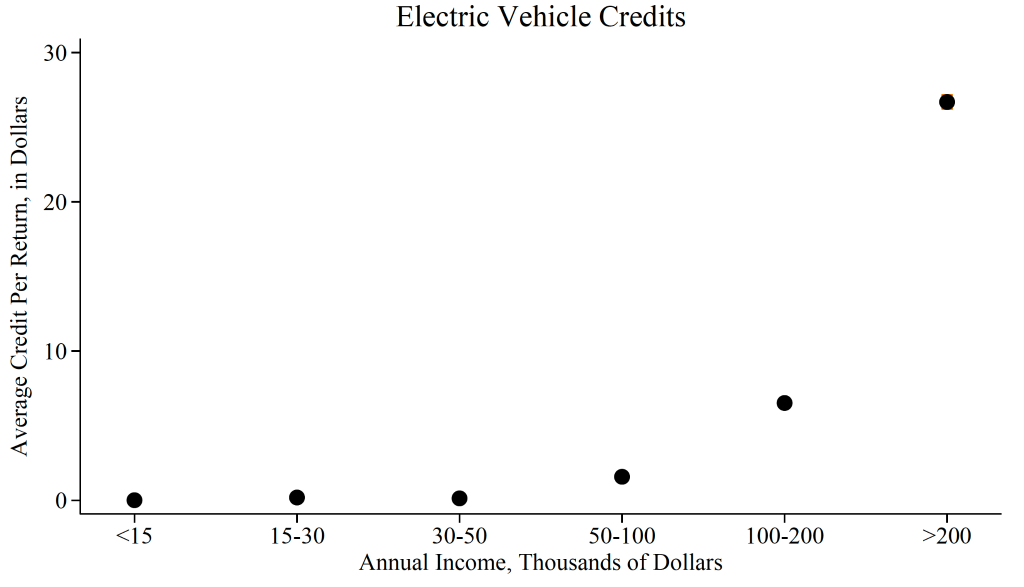

Even more extreme is the tax credit for EVs.

—

As the figure above illustrates, the average credit per return – which accounts for both the size of the credit and the share of returns that claim it – was less than $2 for filers with income below $100,000, $9 for filers with income $100,000-$200,000, and then $27 for filers with income above $200,000. Overall, the top quintile received more than 80% of all EV tax credits.

—

Time After Time

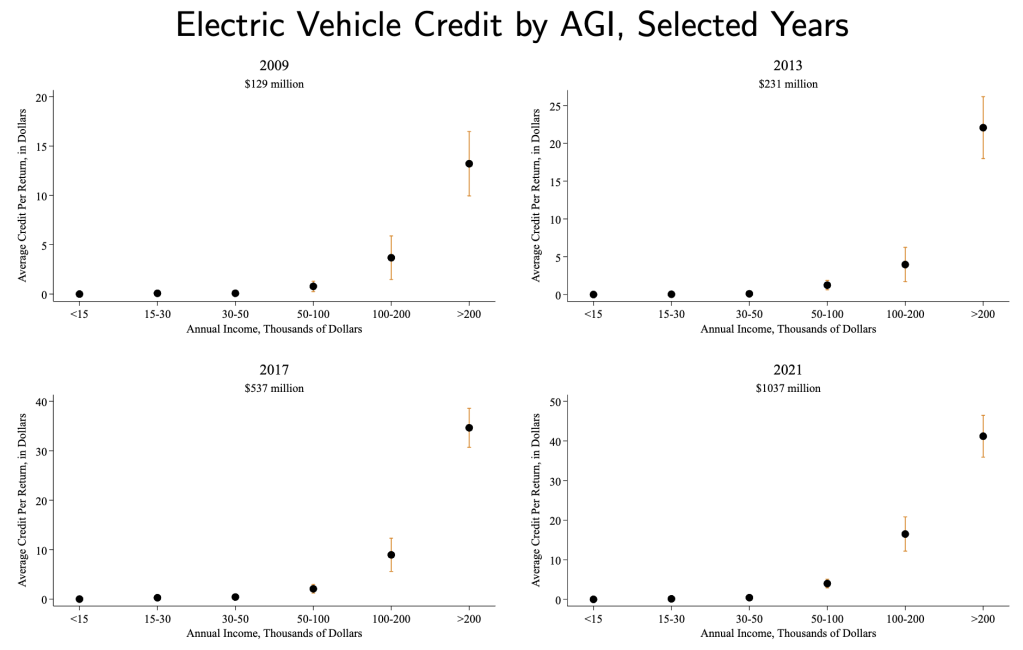

But how has this changed over time? Rather than combining all the years together, the figure below shows the pattern for individual years at four-year intervals.

—

We find that, year after year, the pattern is the same. Across all 16 years in our data, we find that 60% of residential energy credits go to the top income quintile. Relative to a similar analysis that we conducted about a decade ago, we’ve added nine additional years of data, yet the overall pattern of distributional effects is almost exactly the same.

The distributional pattern for EV credits is also very similar across years. See the figure below. Across all years, we find that 80%+ of EV tax credits go to the top income quintile.

—

This lack of change over time is somewhat surprising. The markets for heat pumps, solar panels, and EVs have matured substantially over this time period. With EVs, we’ve gone from only two models being available to more than 100 models being available today. With residential solar, total U.S. capacity has increased more than 50-fold. Despite all these changes, we see little evidence of a broadening across the income distribution.

—

What About Leases?

One disadvantage of working with household tax return data is that they do not include tax credits from leases. This is a major share of the market for EVs and residential solar, though not really relevant to heat pumps or most types of energy-efficiency investments.

When a household leases an EV or solar panels, the lessor (e.g. Tesla or Sunrun) is able to claim the tax credit, but the household is not. In order to get a sense of how leasing could be influencing our results we compiled data on how lease shares have changed over time.

—

Interestingly, the lease shares have fluctuated significantly over time. But while the lease share has been going up and down, the concentration of these tax credits among high-income filers hasn’t budged. This suggests that leasing is unlikely to be substantially biasing our distributional analysis.

—

Mechanism

Why do tax credits go predominantly to high-income households?

Part of the explanation is that all of these credits are non-refundable. About 40% of U.S. households pay no federal income tax, so millions of mostly low- and middle-income filers are simply ineligible for these credits. We don’t think there is a good argument for making these credits non-refundable. The objective of these tax credits is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. From this perspective, there is no difference between filers with positive and negative tax liability, so this asymmetric treatment does not make sense.

Another part of the explanation is that neither renters or landlords are eligible for the tax credits aimed at heat pumps and other energy-efficient investments. Over one-third of U.S. homes are rented, so this is a significant omission and another highly asymmetric treatment that is hard to rationalize from a greenhouse gas perspective.

In future work it is going to be very interesting to see if and how these patterns change with the IRA. One of the biggest changes is a move toward point-of-sale subsidies. Starting in 2024, for example, the tax credit for EVs has been available at the point-of-sale. There are also new maximum income requirements for EV purchases (though not for leases) and other design features specifically designed to address who gets these credits. These are potentially quite significant changes so stay tuned.

—

The Takeaway

So, are clean energy tax credits a good idea? Ultimately, in evaluating tax credits or any public policy it makes sense to think about both equity and efficiency. Our new paper is mostly about equity and mostly bad news, with the lion’s share of these tax credits still going to higher income households.

What about efficiency? Although tax credits may initially seem like a good idea, they have several serious limitations relative to first-best policies like a carbon tax. Perhaps most importantly, tax credits don’t help achieve the efficient level of usage. Take passenger vehicles for example. A tax credit can encourage households to buy an EV, but it cannot get people to drive less, or take public transportation, or to ride a bike. A carbon tax, in contrast, would encourage people to reduce gasoline consumption along all margins.

Then there is the question of how much tax credits change household behavior, i.e., how many additional purchases of these clean energy devices they create. Unfortunately, many recipients receiving the tax credit would have made the purchase regardless. Our paper presents some suggestive evidence (more on this in a future blog post), but understanding adoption behavior better is a key priority for future work.

Tax credits are also extremely coarse instruments. The amount of carbon abatement achieved with a heat pump space heater depends on how cold it is where you live, the size and thermal efficiency of your home, and on what type of heating you would use otherwise. A carbon tax, for example, would create stronger incentives in places where heating is more important, but none of this can be reflected with a single nationwide uniform subsidy.

Probably the biggest advantage of tax credits is political palatability. I don’t pretend to understand what is possible or not possible politically, but I do think it is worth recognizing that the U.S. preference for “subsidize green” over “tax brown” comes at a high cost in terms of economic efficiency. Moreover, the distributional impacts are a real concern. Through several key features of the tax code, we have set up these credits in a way that tilts the benefits towards the highest-income households.

—

—

For more see, Borenstein, Severin and Davis, Lucas. “The Distributional Effects of U.S. Tax Credits for Heat Pumps, Solar Panels, and Electric Vehicles” Energy Institute Working Paper, (June 2024), WP-348.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Clean Energy Tax Credit Concerns” Energy Institute Blog, June 17, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/06/17/clean-energy-tax-credit-concerns/

—

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

—

By default comments are displayed as anonymous, but if you are comfortable doing so, we encourage you to sign your comments.

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

“Why do tax credits go predominantly to high-income households? Part of the explanation is that all of these credits are non-refundable. About 40% of U.S. households pay no federal income tax, so millions of mostly low- and middle-income filers are simply ineligible for these credits. We don’t think there is a good argument for making these credits non-refundable.”

In terms of equity and optimizing GHG emission reductions, I agree. But given that this is an economics blog, I think that the fact that refundable tax credits are scored as capital outlays whereas non-refundable credits are scored as forgone revenue needs more attention on the budgetary side. I’ll leave it to economists and other taxation wonks to determine if there is a notable difference in the straight cost of reducing GHG emissions through both types of credits. Refundable credits certainly work well for the EITC and have a solid dynamic impact in tax terms. But I will stop short of applying that to other refundable credits without more data.

Kurt Schuparra

As OSD notes, the goal is to reduce carbon emissions. So we need to incentivize the acceleration of these technologies everywhere we can. Period. All these equity concerns (and the attempts to hitch every other social problem to carbon policy) only serve to handcuff the carbon reduction mission. So you need to decide: (A) reduce carbon reductions as fast as possible to address the existential threat of climate change, OR (B) explore equity and all that other stuff. One or the other. You cannot have both.

MSW