Are Clean Energy Tax Credits Equitable?

Income tax credits for solar panels and electric cars go overwhelmingly to high-income households.

Over the last decade, U.S. households have received more than $18 billion in federal income tax credits for weatherizing their homes, installing solar panels, buying electric vehicles, and other clean energy investments. In a new EI@Haas working paper, available here, Severin Borenstein and I use tax return data from the IRS to examine the socioeconomic characteristics of filers who receive these credits.

We first examine a set of income tax credits aimed at residential investments in energy-efficiency and renewables. Between 2006 and 2012 the largest categories of investments were energy-efficient windows ($4.0 billion), qualified furnaces ($2.4 billion), qualified air conditioners and water heaters ($2.4 billion), ceiling and wall insulation ($2.0 billion), and solar photovoltaic systems ($1.8 billion).

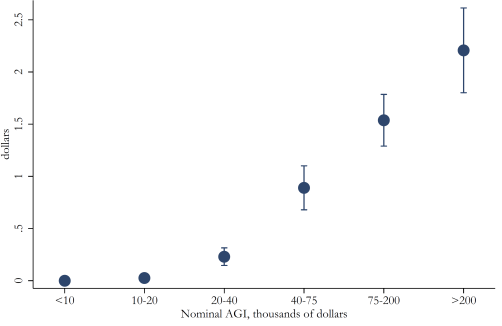

The figure below shows how use of these credits varies across income levels. We divided tax filers into six categories based on their Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). The first five categories are approximately quintiles, and then the last category ($200,000+) includes about 3% of returns.

Income Tax Credits for Clean Energy Residential Investments

Average Credit per Tax Return, By Income Level

The figure shows a strong positive correlation with income. Filers with less than $40,000 in AGI receive less than $10 in credits on average per tax return. The average credit amount more than doubles for filers with $40,000-$75,000 and then doubles again for filers with $75,000-$200,000 in AGI. Finally credits reach $80 per return for filers with AGI above $200,000. The figure above also plots 95 percent confidence intervals, though they are barely visible except for in the highest income category.

Another significant tax credit is the Alternative Motor Vehicle Credit, which provided a credit for hybrid vehicles until 2010 and continues to provide credits for natural gas, hydrogen, and fuel cell vehicles. As the figure below shows, this credit exhibits the same strong positive correlation with income. The bottom three income quintiles receive about 10% of all credits, while the fourth and fifth quintiles receive about 30% and 60%, respectively.

Alternative Motor Vehicle Credit

Average Credit per Tax Return, By Income Level

Finally, we looked at the Qualified Plug-in Electric Drive Motor Vehicle Credit, an income tax credit for electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. The size of this credit ranges from $2,500 to $7,500 depending on the battery capacity of the vehicle. For example, the Toyota Prius plug-in hybrid qualifies for a $2,500 credit whereas the Chevrolet Volt qualifies for a $7,500 credit.

We find that this credit is considerably more concentrated in the highest income categories. As shown in the figure below, filers with less than $75,000 in AGI rarely claim the electric vehicle credit. The average credit amount jumps considerably in the $75,000-$200,000 category and then soars in the top AGI category ($200,000+).

Electric Vehicle Credit

Average Credit per Tax Return, By Income Level

Thus overall, we find that filers with AGI in excess of $75,000 receive about 60% of the tax credits aimed at energy-efficiency, residential solar, and hybrid vehicles, and about 90% of the tax credit aimed at electric cars.

We find that tax credits are less attractive on distributional grounds than pricing GHGs directly. Previous studies (here and here) have examined how a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program would impact households with different income levels. Whereas tax credits go disproportionately to high-income households, a carbon tax would be paid disproportionately by high-income households. It would seem difficult, therefore, to argue for tax credits on distributional grounds.

Our data come from individual income tax returns, so they miss tax credits received for electric vehicles and solar panels that are leased. Leasing has grown more common in both markets, though especially in the solar market with the well-documented move toward third-party ownership. However, previous research finds that the decision to lease is uncorrelated or even slightly positively correlated with income, so leasing is unlikely to undo the pronounced positive correlation between credits and income.

Why are these tax credits so concentrated among the higher income categories?

Part of the explanation is that all of these credits are non-refundable. You can use these credits to offset your tax bill, but you cannot go negative and receive a net payment from the IRS like you can with the Earned Income Tax Credit and many other tax credits. This is a significant distinction because a large fraction of filers do not have positive tax liability. In 2012, for example, more than one-third of U.S. tax returns had zero tax liability. These filers without tax liability tend to be lower-income, so this helps explain the low take-up in lower income categories. Making these credits non-refundable doesn’t make much sense. After all, what is the real difference between a filer who owes $0 in tax and another who owes $1000? Both reduce carbon emissions when they install an energy-efficient window. Both stimulate innovation when they purchase an electric vehicle. So it seems odd to treat these filers so differently in our tax code.

Another issue is that renters are ineligible for most of these credits. Over 40 million American households are renters, and thus cannot take advantage of any of the credits aimed at weatherization, energy-efficiency, or solar PV. Addressing renters is challenging because of imperfect information and split incentives, but excluding this sector altogether misses a large share of the housing stock. The proportion of households that own a home increases steadily across income quintiles from 0.49 to 0.91 (here), so excluding renters disproportionally impacts lower-income households.

With the electric vehicle credit there are also a couple of additional potential explanations. It may simply be that, for the moment, electric vehicles are only affordable for relatively high-income households. Even after the credit, electric and plug-in electric vehicles are expensive compared to equivalently-sized gasoline-powered vehicles. Finally, another possible explanation is that in California, electric vehicles owners are allowed to drive in high-occupancy vehicle lanes. The value of time is highly correlated with income so this could help explain why this credit is so highly concentrated in the highest income categories.

So what? Should we scrap these tax credits? Should we expand them to include more Americans? Ultimately, in evaluating tax credits or any public policy it makes sense to think about both equity and efficiency. Our new paper is mostly about equity, and the results imply that it probably does not make sense to argue for these tax credits on distributional grounds.

What about efficiency? Although tax credits may initially seem like a good idea, they are actually quite a poor substitute for first-best policies like a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program. Probably the single biggest limitation of a tax credit is that it cannot achieve the efficient level of usage. Take energy-efficient windows as an example. A tax credit can encourage households to install better windows, but it cannot get households to use less heating and air-conditioning. A carbon tax, in contrast, would encourage households both to install better windows and to use less heating and air-conditioning.

Tax credits are also extremely coarse instruments. The social benefits from clean energy investments vary enormously by geography. For example, a new paper by Stephen Holland, Erin Mansur, Nick Muller and Andrew Yates finds that the environmental benefits from electric cars varies from $3000 in California (where most electricity comes from natural gas and renewables) to -$4700 in North Dakota (where most electricity comes from coal). Tax credits ignore this heterogeneity completely, whereas price-based policies would incorporate these differences.

In the end, it is hard not to be somewhat disappointed. The more we have studied these tax credits, the more we realize their limitations. There are large potential social benefits from clean energy investments, but income tax credits are an inefficient instrument for realizing changes in behavior. Moreover, the distributional impacts are a real concern. Through several key features of the tax code, we have set up these credits in a way which excludes millions of Americans from participating, and higher-income households receive the lion’s share of total credit dollars.

For more, see “The Distributional Effects of U.S. Clean Energy Tax Credits” (with Severin Borenstein), NBER Tax Policy and the Economy, 2016, 30(1), 191-234.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Are Clean Energy Tax Credits Equitable?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, July 20, 2015,

https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2015/07/20/are-clean-energy-tax-credits-equitable/

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

Specifically related to the EV Tax Credit.

First, there should be a comparison of non-plug in purchasers at the same price points. Being able to afford a new car limits lower income levels. Encouraging people that would be buying a new car anyway, to adopt new cleaner technology should be a positive. These purchases lower technology costs and builds a fleet of used vehicles for lower income buyers.

Second, the study completely misses leasing. If a buyer cannot use the entire tax credit (because of low income), they can lease the vehicle and get the full benefit of the tax credit. The manufacturer takes the credit and passes the value into low monthly lease prices. To my knowledge the majority of credits have been claimed through leases. Excluding Tesla sales which have not offered leases until recently.

Tax reductions favor those who have meaningful tax bills to be reduced. But what if the carbon tax were not really a tax but a fee that would be 100% returned to all adult legal US citizens on an equal-share, per-capita basis, regardless of income or property ownership? This how the oil royalties collected by the Alaskan government are handled.

It’s the concept behind Citizens’ Climate Lobby. http://citizensclimatelobby.org/carbon-fee-and-dividend/

This paper identifies strong correlation between higher income electricity consumers and their use of federal tax credits aimed at energy-efficiency, residential solar, hybrid vehicles, and electric cars. This finding is consistent with the purpose one can assume for clean energy tax credits. The tax credits would act as a subsidy and an incentive to guide energy saving investment decision. This being the case, it is not surprising that almost all tax credits claimed are by income categories exceeding $ 40,000 annually. Higher income electricity consumers have two major incentives to invest in energy savings measures discussed here: higher disposable income and hence higher propensity to invest and higher electricity bills in reflection of higher tiered electricity rates but also larger electricity consumption base. All said investments in energy savings by higher income electricity consumers will result in higher savings per household as compared with lower income households and higher reduction in marginal cost of electricity on kWh basis as compared to the lower income household.

Given the above, it is imperative that we distinguish between clean energy tax credits and other instruments such as pricing of GHG in terms of their application as policy instruments and their overall effect whether on equity or efficiency. Clean energy tax credits are subsidies aimed at enhancing the adoption of specific energy saving technologies. Hence the tax credits are investment decisions enhancing instruments. Moreover, unless clean energy tax credits are supplemented with programs targeting lower income groups to include measures such as equipment replacement or programs that offer financing and / or direct rebates in addition to clean energy tax credits, clean energy tax credits would undoubtedly result in benefitting the top 40% tax filers and those with higher income. A GHG tax or price direct impact on the other hand is on consumption and not the investment decision and technology choice. A residual effect on investment is there but the key impact is on consumption of electricity. This important distinction should be taken in consideration in my view when accounting for equity and efficiency in the case of both clean energy tax credits and pricing of GHG.

Policymakers are likely to continue to look to subsidies as an instrument to advance the adoption of clean energy technologies. The potential is high that clean energy tax credits will continue to be the preferred approach. This being the case, I would strongly suggest the following as a follow-up or accompaniment to this study:

• Policy program evaluation and impact analysis post implementation of federal clean energy tax credit programs – It is important that post investment and impact analysis of federal clean energy tax credits is conducted to ascertain that the program was executed in line with the original objectives and the degree and reasons as to which its objectives were met or not. Post investment analysis can feasibly explain the strong correlation between income and the use of tax credits. Post investment analysis can ascertain as to whether electricity tiered rate effect and the larger purchasing power of higher income electricity consumers was fully evaluated in the design of the tax credits. Of particular interest is evaluation of the clean energy tax credits effectiveness on the basis of program implementation and on the energy picture of the national economy akin to financial versus economic impact analysis.

• Assessment of the institutional framework ability to execute such programs and to achieve the desired results – It will be of interest to examine the effect the institutional framework had on the legislation and the implementation of clean energy tax credits. It will be interesting to know any role regulatory capacity, economic analysis and capacity, role of constituencies and stakeholders, and program administrative matters (information dissemination, application approvals, etc. on the spatial level) had on clean energy tax credits.

• Field research work – Field work particularly randomized controlled experiments can also tell us on electricity consumer behavior regarding investment decisions given clean energy tax credits or not.

I regard the results of this study as quite significant.

One wonders about the relevance of the question. While Mr. Benson’s reference to Betteridge is appreciated, undoubtedly some readers are really wondering why this question seemed to be even remotely interesting. Presuming that clean energy investments are normal and not inferior goods, obviously demand rises with income. To quote the average California 14 year old: Duh! Of course higher income consumers are going to make more clean energy investments.

With any type of policy incentive, the appropriate question should be focused on the impact of the policy as an incentive lever. In the case of energy efficiency, clean energy investments or clean transportation investments, the question should focus on the counterfactual. One must evaluate the behavior without the tax credit policy lever and then compare this to behavior in the presence of the policy lever. That question will allow policy-makers to better understand the impact of policy on the desired environmental activity.

Now, having done this, those analysts also interested in the relative impact across income levels could perform a differences-type analysis to compare the policy responsiveness by income quintile. Still, one could expect that the impact of tax policy on clean energy investment among lower income consumers will be minimal at best, even if the policy allows a refund of the tax credit. For X goods with sufficiently small consumption, the budget constraint between X and Y (where Y = AOG) will nearly track the vertical axis. As such, neither an income or substitution effect would be very large.

But again, one asks why even this question is interesting? Take another step with the reasoning of the policy-makers. (No jokes about policy-makers having no reason) A rational policy-maker, in the presence of limited policy resources, should want to spend those policy resources as efficiently as possible, in order to maximize policy outcomes.

In other words:

It is perfectly acceptable for policy to promote a cleaner

environment via the wealthier members of our society!

Then again, perhaps this writer has it completely wrong. Perhaps policy-makers (and policy consumers) in California truly are more interested in distribution over actual environmental impact. Perhaps the popular support for a strong environmental hand has compelled policy-makers to exploit this in order to promote their true goal of re-distributive policy in the name of environmental protection.

One hopes not.

I’m wondering if your last paragraph is naive or sarcastic. I couldn’t have written a better paragraph about how politicians use laws with superficially socially desirable goals to gain support from particular interest groups. Anne Krueger’s rent seeking paradigm is relevant here. So yes, distributional concerns, by the nature of the political process, largely trump overall societal goals. The key to developing successful policies is designing them so that the societal and interest group objectives are more closely aligned. Unfortunately, the interest groups don’t always know what’s really best for themselves because they are deceived by “trusted” advisors such as tax accountants and lawyers who actually have a stake in the outcome.

So, yes policymakers and their advisors are very interested in this paper because they care first and foremost about how certain groups of their constituencies are affected.

Primary political objectives:

1. Get elected.

2. Get re-elected.

I wish that my last paragraph were naive. That would make me much younger, if nothing else! But perhaps there is something more than sarcasm in the paragraph. If we have to wait for environmental progress from programs that hit an arbitrary equity target, do we really stand a chance of addressing climate change?

Given the nature of sea level rise, this the following is likely an unfortunate metaphor. But, so long as it would be enough for a policy to make all boats rise up, in a Rawlsian sense, then perhaps there is a better chance of success.

I find these articles interesting because they don’t begin with the key question, which is: what is the intended objective for providing a subsidy for a new energy or any other type of technology? One objective would be to offset the cost for the customer purchasing the device? In that case a rebate might work better than a tax credit, although as this paper points out both of these options would tend to favor higher income customers.

If the objective is to lower costs and accelerate the commercial development of a technology, besides government sponsored research there are two other potential options: (1) provide grants to companies to incentivize development – unfortunately this puts the governement in the position of picking winners and losers, or (2) why not consider volume-based government (federal, state, and local) purchases before pushing a new technology into the retail market. Why not convert government fleets to EV and put solar, storage, and EE tech options on all government buildings? Volume-based implementation to support public services benefit all “customers” much more equitably than tax credits or rebates while also providing manufacturing volumes to achieve scale production. With proper oversight using government purchases provides an opportunity to more closely study and evaluate technology options and to also flush out design and implementation practices before moving to full retail markets.

While government fleets and buildings may be promising applications, there are two problems. First is that they actually aren’t often that high of volume so scale economies may not be substantial, particularly if many different vendors are used. And they have almost no penetration into the residential building market, certainly not single family which 80% of the market.

But the second problem is bigger–early adopters test the products and are more attuned to the failings and highlights of the products of the services. They get out the word of mouth that drives market success. Governments are by their nature exactly the opposite–highly risk averse, often opaque in their operations. And they have a growing trust issue with veracity with the public.

Early adopters also tend to have higher incomes, which tends to go with risk taking. So we need to ask whether the subsidies to early adopters, who also happen to be higher income, create benefits in the future for those with lower incomes? There’s other ways that we need to address income distribution.

sounds like “trickle-down renewables”. First let the rich guys lower their electric bills on their swimming pools and McMansions, then they’ll provide feedback that someday benefits the non-wealthy?

The solar ITC is flawed, let’s scrap it. It is horribly socially discriminatory, disincentivizes price reductions, and sends a large portion of tax dollars straight to China to advance their industry dominance, not ours. The current ITC is already “picking winners” and sadly they are foreign.

A better way is grants & loans for US solar/wind manufacturing (supply) combined with financing for competitive tenders for utility-scale solar/wind projects (demand with scale efficiencies) factoring in both price and US content. Utilities would compete to win these projects and financing by offering the lowest pass-through costs benefitting all ratepayers (not just upper-class, as is now).

This would ensure 1) strong growth ins US renewables manufacturing, 2) strong growth in US renewables installations, 3) more US jobs, and 4) more taxpayer dollars recycled into the US economy, not China’s.

In a republic, government has to overcome a significant hurdle to install a new tax. One of the reasons for this difficulty is that citizens implicitly understand that the tendency is for the government to borrow against any new tax revenue in order to garner political support, and thereby increase the structural deficit. This explains paradoxically why new taxes, once installed, are even harder to remove.

In short, the problem is not in the efficiency or equity of a carbon tax. The problem is in the practical difficulty of ensuring that the revenue would be spent on carbon. The most “sequestered” tax we have is Social Security, and if you look at the governments own published records it is obvious that 100% of the social security surplus was put back into government bonds. This may not be easy for the average person to understand, but in fact it means that the excess funds contributed that are needed for retirement have already been spent by other government departments and then further borrowed against future social security tax revenue.

One advantage of tax credits, and maybe the only advantage, is that you have to invest first and get the credit afterward. It does well on guaranteeing the investment actually happened. No surprise most of the credit goes to those that have the means to make the investment, aside from the obvious need to have income against which the credit can be applied. I believe the reason we do not have effective carbon tax or cap-and-trade on most of the world’s carbon-intensive GDP is this suspicion that the revenue will not be used for carbon.

There’s no reason why the revenues from a Pigouvian tax such as carbon tax must be recycled into carbon reduction activities. You will find nothing in the economic literature justifying revenue recycling in this manner as prerequisite–it’s only politicians demanding this. The carbon tax is intended to increase PRIVATE investment in carbon-reduction strategies WITHOUT government intervention or assistance. The carbon tax reflects the government claiming a public trust property right to the atmosphere, and charging a “tipping” fee for discharging GHGs. We don’t demand that corporations use the revenue from their product sales solely for reinvesting into their business activities–they can use those funds however they choose. The carbon tax revenues can be used to offset other tax revenues that cause greater inefficiency in the economy, e.g., income taxes. A lot of research has been done on this effect.

I don’t understand why you should earmark the tax revenue from taxing a “bad” to mitigate that “bad” further. The existence of a properly sized Pigovian tax should be enough to redirect economic activity away from the activities that create the negative externality. For example, several economists including Joe Stiglitz are suggesting that carbon tax revenues should be used to reduce income tax for low income earners. Expanding their consumption ability may even be against the efficiency of the carbon tax itself (because research shows that wealthier people have larger environmental footprints) but it is an effective distributional policy with likely positive welfare effects. In fact, in many jurisdictions around the world earmarking taxes is not allowed so your tax dollar on gas may be used to fund healthcare, for instance.

Regarding the reasons for not having an effective carbon tax (or a carbon tax at all) it shows to be much more related to the distributional effects of such a tax/price on carbon (and the allowance allocation in the case of a carbon cap and trade structure) than efficiency concerns.

It is interesting to note that many of the energy saving tax credit don’t benefit the poor, because they pay little or nothing in taxes. This has always been obvious. This is one of the unintended consequences of using the tax code as a method of changing behavior. The same can be said for the electric vehicle and hybrid vehicle stickers that give single driver access to diamond lanes and toll lanes. As to rental properties, tax credits help the owner of the property to install energy saving windows and other things. The renter doesn’t benefit from this at all. However, if the renter had to pay the carbon tax, he would benefit along with the building owner. In the case of rental properties a case for both a tax credit and a carbon tax can be made.

In the split incentive problem, the property landlord doesn’t benefit in any way from installing energy savings windows either unless the building has only a single meter (which is fairly uncommon, at least in California). The tenant usually benefits. The problem is aligning the landlord and tenant interests to achieve improved energy efficiency.

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines strikes again.