Do High Interest Rates Threaten the Green Transition?

Increased borrowing costs make long-term investments more expensive.

Depending on which headlines you’ve been reading, you might have gotten the sense that all is not well with the green transition. Recent weeks have seen a bevy of dropped projects and tempered ambitions. Orsted canceled a high profile offshore wind project in New Jersey. One estimate suggests that a full 30% of state-contracted offshore wind projects have been scuttled. GM and Honda nixed a major partnership to make electric vehicles, while GM dropped its EV production targets and Ford announced a major delay in EV spending. The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF, a benchmark index of clean energy stocks, was down 30% year-to-date last week, against a 7% increase in the Dow.

Wind projects like these are evidently not headed to the Jersey Shore. (Photo source: NYTimes)

If you click through and read these stories, one common thread is the role of higher interest rates. Central banks have been holding interest rates “higher for longer,” and this change in borrowing conditions has become an oft-cited reason for green project slowdowns. Are today’s interest rates a real roadblock, or just a quick bump in the road?

Why are high interest rates bad for the green transition?

Higher interest rates make it more expensive to borrow or spend money today. Higher borrowing costs make it more expensive to invest in fossil fuels as well as green technologies, but higher borrowing rates present a relative disadvantage for green technologies for three main reasons.

First, green technologies tend to trade off higher up front costs against lower operating costs, which means that borrowing costs have a higher proportional effect on green investments. This is most acute for solar and wind, which get free fuel from nature and thus have total costs heavily skewed toward upfront capital and installation. Natural gas plants, in contrast, have a more balanced mix of costs and are thus less sensitive to an increase in financing rates. The same principle applies to EVs, which exchange a higher up front purchase price for lower cost per mile, as compared to gasoline alternatives.

Second, green technologies are inherently about change. Higher borrowing costs slow overall investment and slow down churn. When borrowing is hard, households will hold onto their existing vehicles, air conditioners and furnaces for longer, which slows down the natural turnover that favors cleaner goods. On the supply side, electrification requires massive investment in transmission, and carbon capture calls for new pipelines and lots of capital.

Third, more nascent green technologies–think storage, direct air capture and electrolysis–still need a heavy dose of pure research and development. R&D costs more when money is expensive, so a world with higher interest rates favors incumbents.

How much have interest rates changed, and is this enough to matter?

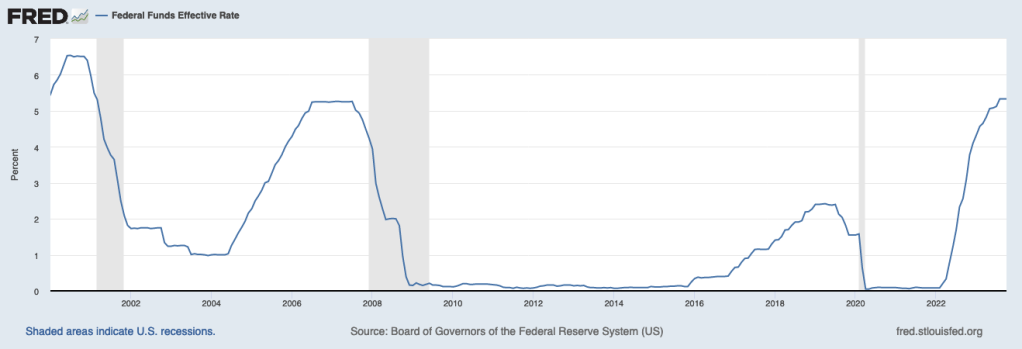

The most salient benchmark interest rate in the US is the Federal Funds Rate, which governs interbank lending and which the Federal Reserve Board directly controls. The effective Fed Funds Rate currently sits at 5.25%, a 22-year high. The Federal Funds Rate spent most of the last dozen years at a nice cozy 0%, and we have to rewind to the Bush Administration to find rates higher than we have today.

The Effective Federal Funds Rate is at a 22-year High (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Estimates from the IEA suggest that a 5% increase in the borrowing costs applied to a project raises the levelized cost of wind or solar by as much as 50%, while having a single digit impact on a new gas plant.

And, in case you missed it, the cost of renewables has risen since 2020. The initial shock was due to commodity price spikes, which have since stabilized, but elevated financing costs mean that the IEA projects that the levelized cost of solar and wind in 2024 will remain higher than their pre-pandemic benchmark.

On the other hand, things may not be that bad

A five percent swing in interest rates is a big deal for borrowing. But, the Federal Funds Rate is a nominal rate, a rate that does not adjust for inflation. We have high interest rates in part because we are reckoning with inflation, and economists normally think the thing that matters most for investment is the real interest rate, which adjusts for inflation. The change in borrowing costs looks less dramatic when one adjusts for inflation. The 10-year real interest rate on US Treasuries calculated by the Federal Reserve, which projects inflation based on a collection of forecasts, shows something closer to a 2% increase over the last couple of years.

Real Interest Rates are Elevated, but Far Less than the Nominal Rate (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

A 2% increase is nothing to sneeze at, but conventional estimates show that, even with elevated financing costs, renewables remain the cheapest source of power. Modest moves in the interest rate will push marginal projects out of the money and slow down renewable deployment, but it won’t flip the big picture. So, consider this a notable headwind, but not an existential threat.

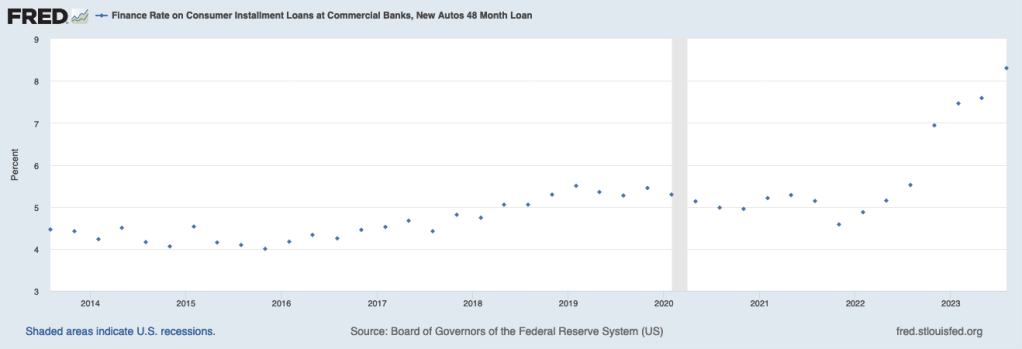

While economists argue that the inflation-adjusted real interest rate is the most relevant for decision making, it may well be that households are sensitive to nominal rates that affect their perception of borrowing costs. The Fed collects data on the interest rate on car loans, which shows that the average rate for new car loans has recently jumped above 8%.

Nominal Rates on Car Loans have Jumped, Making EVs a More Expensive Option (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Conventional wisdom suggests that car buyers focus on monthly payments. The average EV costs more than $50,000. If a car buyer financed the entire amount with a four-year loan, a jump from 4% to 8% in the loan rate would increase the monthly payment by about $90. This is more than the drop in monthly payments due to the $7,500 federal EV tax credit, which would knock down the monthly payment in the same scenario by around $80.

But, most buyers won’t finance the entire amount, and higher interest rates raise the monthly payment of internal combustion engine vehicles as well, which are selling for only about $5,000 less on average. For a consumer choosing between an EV and a conventional vehicle, if the EV price premium were $10,000, the jump from 4% to 8% on a 48 month loan only changes the relative payment by about $20 a month. This might still matter for some car buyers, but my suspicion is that higher borrowing costs will mostly impact EV purchases by depressing overall new car sales, as buyers hold onto existing cars longer, rather than causing them to choose a new conventional vehicle instead of a new EV.

Looking ahead

Last year, Reuters surveyed a bunch of economists, and they agreed that higher interest rates were of mild concern for the green transition. I tend to agree–whether real interest rates are 0% or 2% or 3%, the green transition in the US is likely to march along, though there will be some slow down on the margin.

Recent news from the most hawkish Fed governors suggests the current rate “pause” may be extended. We may already be looking at peak rates. So, we should keep our eye on these macro factors, but the bigger issue with financing and the green transition is probably about ensuring access to capital in lower-income countries, not worrying about the Federal Funds Rate in the US.

This view, however, hinges critically on the presumption that policy support from the IRA and related mechanisms remains robust. And high interest rates may yet have a role to play in this regard.

Most provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expire in 2025, which means that after next year’s election, Washington will almost certainly have to reckon with tax policy. This fiscal debate will happen in the shadow of a rapidly growing national debt, fueled by both recent spending (including the IRA) and rising debt financing costs due to higher interest rates. Recent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office projected that the annual cost of financing the national debt would exceed $600 billion in 2023 and total $10 trillion in the subsequent decade. The federal debt takes on a completely different dynamic at higher interest rates, and these budgetary pressures could quickly rise in importance, as argued here.

How might this impact environmental policy in the 119th Congress? In one (wildly?) optimistic scenario, a need for revenue could reignite interest in pricing carbon. On the other hand, a higher debt load offers a reason (or a pretense) for gutting the aggressive green subsidies passed by the Biden Administration. In a twist of irony, to get lower rates and thus ease debt financing costs, we may need a fair bit of inflation reduction in order to save the Inflation Reduction Act.

Of course, which path we take depends most importantly on who sits in the White House and who controls Congress in 2025. Thus, if high interest rates today impact the electoral outcome itself–either by taming inflation or by fueling perceptions of a poor economy–that may well be the most significant way in which the Fed’s decisions on rate’s today affect the green transition of tomorrow.

Suggested citation: Sallee, James. “Do High Interest Rates Threaten the Green Transition?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, December 4, 2023, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2023/12/4/do-high-interest-rates-threaten-the-green-transition/

Categories

James Sallee View All

James Sallee is a Professor in the Agricultural and Resource Economics department at UC Berkeley, a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, and a Faculty Research Fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Before joining UC Berkeley in 2015, Sallee was an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. Sallee is a public economist who studies topics related to energy, the environment and taxation. Much of his work evaluates policies aimed at mitigating greenhouse gas emissions related to the use of automobiles. Sallee completed his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Michigan in 2008. He also holds a B.A. in economics and political science from Macalester College.

“In a twist of irony, to get lower rates and thus ease debt financing costs, we may need a fair bit of inflation reduction in order to save the Inflation Reduction Act.” Indeed.

In another “twist of irony,” in 2009, the $90 billion for “green” energy projects in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act — which Biden had a major hand in — went a very long way in saving wind and solar projects when banks were extremely reluctant to lend — notwithstanding very low interest rates. Now, with the IRA already in full swing, government can’t come to the rescue of clean energy projects without lower interest rates.

Every investment is a bet. One looks at the risks vs rewards. I buy a lottery ticket when the prize is over a billion. It is all but certain that I’ll lose my two bucks, I buy anyway because the reward, for me, out weighs the risks.

Now with green investments. your ROI will probably be really low, even negative. But if we don’t invest green, your other investements will be guaranteed to be a100% negative ROI.

Until people realize that if we don’t do what we can do to mitigate climate change, the existential threat is certain. Here’s the best answer for discussions like this: 42 Angels on the head of the pin.

OSD