Addicted to Oil: U.S. Gasoline Consumption is Higher than Ever

Many people thought U.S. gasoline consumption had already peaked. They were wrong.

Gas is cheap and Americans are back in their cars and trucks. viriyincy/flickr, CC BY-SA

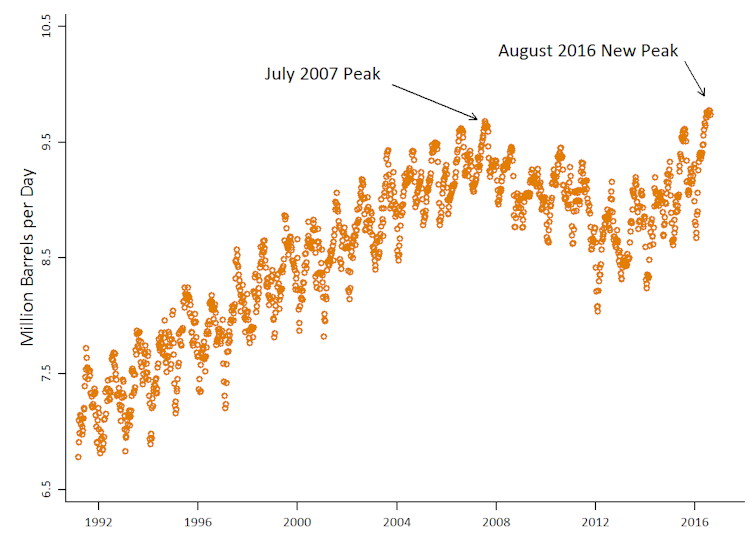

August was the biggest month ever for U.S. gasoline consumption. Americans used a staggering 9.7 million barrels per day. That’s more than a gallon per day for every U.S. man, woman and child.

The new peak comes as a surprise to many. In 2012, energy expert Daniel Yergin said, “The U.S. has already reached what we can call`peak demand.” Many others agreed. The U.S. Department of Energy forecast in 2012 that U.S. gasoline consumption would steadily decline for the foreseeable future.

Source: Constructed by Lucas Davis (UC Berkeley) using EIA data ‘Motor Gasoline, 4-Week Averages.’

Source: Constructed by Lucas Davis (UC Berkeley) using EIA data ‘Motor Gasoline, 4-Week Averages.’

This seemed to make sense at the time. U.S. gasoline consumption had declined for five years in a row and, in 2012, was a million barrels per day below its July 2007 peak. Also in August 2012, President Obama had just announced aggressive new fuel economy standards that would push average vehicle fuel economy to 54 miles per gallon.

Fast forward to 2016, and U.S. gasoline consumption has increased steadily four years in a row. We now have a new peak. This dramatic reversal has important consequences for petroleum markets, the environment and the U.S. economy.

How did we get here? There were a number of factors, including the the Great Recession and a spike in gasoline prices at the end of the last decade, which are unlikely to be repeated any time soon. But it should come as no surprise. With incomes increasing again and low gasoline prices, Americans are back to buying big cars and driving more miles than ever before.

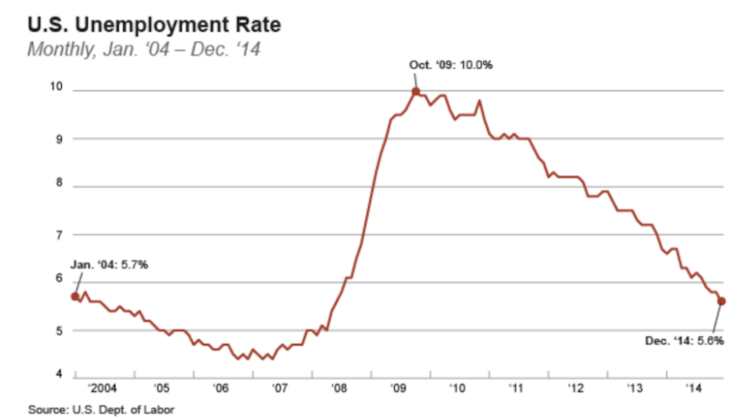

The Great Recession

The slowdown in U.S. gasoline consumption between 2007 and 2012 occurred during the worst global recession since World War II. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the Great Recession as beginning December 2007, exactly at the beginning of the slowdown in gasoline consumption. The economy remained anemic, with unemployment above 7 percent through 2013, just about when gasoline consumption started to increase again.

Economists have shown in dozens of studies that there is a robust positive relationship between income and gasoline consumption – when people have more to spend, gasoline usage goes up. During the Great Recession, Americans traded in their vehicles for more fuel-efficient models, and drove fewer miles. But now, as incomes are increasing again, Americans are buying bigger cars and trucks with bigger engines, and driving more total miles.

Gasoline Prices

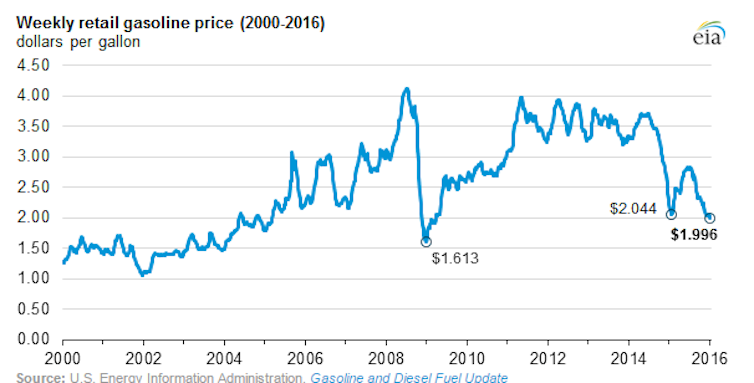

The other important explanation is gasoline prices. During the first half of 2008, gasoline prices increased sharply. It is hard to remember now, but U.S. gasoline prices peaked during the summer of 2008 above US$4.00 gallon, driven by crude oil prices that had topped out above $140/barrel.

Gasoline prices in Washington D.C. top $4 a gallon in 2008. brownpau/flickr, CC BY

These $4.00+ prices were short-lived, but gasoline prices nonetheless remained steep during most of 2010 to 2014, before falling sharply during 2014. Indeed, it was these high prices that contributed to the decrease in U.S. gasoline consumption between 2007 and 2012. Demand curves, after all, do slope down. Economists have shown that Americans are getting less sensitive to gasoline prices, but there is still a strong negative relationship between prices and gasoline consumption.

Moreover, since gasoline prices plummeted in the last few months of 2014, Americans have been buying gasoline like crazy. Last year was the biggest year ever for U.S. vehicle sales, with trucks and SUVs leading the charge. This summer Americans took to the roads in record numbers. The U.S. average retail price for gasoline was $2.24 per gallon on August 29, 2016, the lowest Labor Day price in 12 years. No wonder Americans are driving more.

Can Fuel Economy Standards Turn the Tide?

It’s hard to make predictions. Still, in retrospect, it seems clear that the years of the Great Recession were highly unusual. For decades U.S. gasoline consumption has gone up and up – driven by rising incomes – and it appears that we are now very much back on that path.

This all illustrates the deep challenge of reducing fossil fuel use in transportation. U.S. electricity generation, in contrast, has become considerably greener over this same period, with enormous declines in U.S. coal consumption. Reducing gasoline consumption is harder, however. The available substitutes, such as electric vehicles and biofuels, are expensive and not necessarily less carbon-intensive. For example, electric vehicles can actually increase overall carbon emissions in states with mostly coal-fired electricity.

Americans are buying less fuel-efficient vehicles. http://www.shutterstock.com

Can new fuel economy standards turn the tide? Perhaps, but the new “footprint”-based rules are yielding smaller fuel economy gains than was expected. With the new rules, the fuel economy target for each vehicle depends on its overall size (i.e., its “footprint”); so as Americans have purchased more trucks, SUVs and other large vehicles, this relaxes the overall stringency of the standard. So, yes, fuel economy has improved, but much less than it would have without this mechanism.

Also, automakers are pushing back hard, arguing that low gasoline prices make the standards too hard to meet. Some lawmakers have raised similar concerns. The EPA’s comment window for the standards’ midterm review ends Sept. 26, so we will soon have a better idea what the standards will look like moving forward.

Regardless of what happens, fuel economy standards have a fatal flaw that fundamentally limits their effectiveness. They can increase fuel economy, but they don’t increase the cost per mile of driving. Americans will drive 3.2 trillion miles in 2016, more miles than ever before. Why wouldn’t we? Gas is cheap.

![]() This blog is available on The Conversation.

This blog is available on The Conversation.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Addicted to Oil: U.S. Gasoline Consumption is Higher than Ever”, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, September 26, 2016.

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

Good analysis overall, but two bits of the rhetoric are unhelpful. First of all, as trendy as it’s become, “addiction” is an inappropriate way to characterize oil demand. Oil is a “good” and like many other goods, too much of a good thing creates problems. Any good used at vast scale is bound to have harmful side effects (e.g., externalities). So let’s frame the issue in terms of the problems to be managed, particularly the CO2 problem.

Indeed, oil is so good that it remains, as it has been for many years, the world’s largest source of commercial energy. It’s second to coal in terms of carbon emissions globally, but is easily the main source of CO2 in the United States and is so by a long shot in California. Liquid fuels are way too useful to be dismissed as an addiction, and “getting off of” oil is an absurd goal. That’s not to say that there aren’t opportunities for lower-emitting vehicles, electrification and less auto-intensive urban and regional forms. But none of those options will avoid the need to manage the “Liquid Carbon Challenge” .

The other rhetorical nit to pick is “fatal flaw” for vehicle efficiency and GHG standards. Of course they are not a complete policy, but that’s not fatal; it just means that additional policies are needed. The standards are limiting the growth of transportation oil use and GHG emissions, which is a good thing but hardly enough to seriously bend the curve down. Electric vehicles are costly and capacity limited, and so their benefits will be self-limiting even as the electric power sector decarbonizes.

Higher fuel taxes or a carbon cap/tax would indeed be great complements to vehicle regulations. However, the multiple markets involved in the provision of transportation are far too complex to be adequately addressed by any single policy mechanism, including an economist’s ideal tax. Bottom line: a lot more thinking needs to be done to figure out how to avoid the collision of cars and climate. Carbon offsets, anyone?

Thanks John. Great comment. I completely agree that “addiction” and “fatal flaw” are unhelpful rhetoric and, in retrospect, wish I had phrased both differently.

Reblogged this on Phil Riggan and commented:

For all the ways I’ve been writing about how to reduce our additions to the automobile and to create a more bike and pedestrian friendly place to live, people seem to be more and more comfortable burning up all the fuel we have left as fast as possible.

If you don’t like the news go out and make some of your own. Several possibilities covered in this slide dec.

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1-Q1-a32fs_vNlLcH8gbBC2zOjN0d3vUvz8ZT6eudCdg/edit#slide=id.p

The article mentions the effect of the 2007 recession over the economy and thus gasoline consumption but there’s little to no reference to the over abundance of cheap oil as a result of fracking technologies. It’s a shame that the American public behaves more like a herd of consumers rather than thinking individuals. Those happy SUV owners are in for a little surprise sometime in the next year or so.

For more on this, see my 2014 Columbia University presentation, from min 35 sec 52

I clicked through to the EIA data and when I averaged July ’07’s four weeks, I got 9680.75 and when I did the same for Aug ’16, I got 9675.25. Not exactly a new peak, but close enough.

DOT tells me that July ’07 there were 267e9 VMT, and in July (last month with data) there were 287.5e9 VMT, so there is some small (very small) consolation that we are getting more efficient use of our gas. (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/travel_monitoring/16jultvt/16jultvt.pdf)

It’s not an addiction if it’s driven by low prices. How about “Cheap gas means more consumption”?

It’s sad to see American politicians claim that burning fuel is a human right when the only winners are fat car companies and oil producers. The nation of gluttony is truly puking its childish tantrums all over the world.

“It’s sad to see American politicians claim that burning fuel is a human right when the only winners are fat car ….oil producers.”

In fact, Americans are consuming more oil specifically because oil producers are making less money. Oil producers were minting money when oil was $100 / barrel and US oil consumption was falling. Right now, the producers across the globe are under water financially because oil is cheap.