What’s so Great about Fixed Charges?

There’s a lot of talk in California these days about imposing fixed monthly charges on residential electricity bills. The large investor-owned utilities in California have small or no fixed charges,[1] instead collecting all of their revenue from households through usage-based charges, called volumetric pricing. (And those volumetric prices increase steeply with your monthly usage, the “increasing-block pricing” approach that I discussed in September.)

Interestingly, one of the three natural gas distribution companies in California has a fixed charge, but the other two don’t (SoCal Gas has a charge that is about $5/month. Feel free to chime in if you know how this difference came to be.) Most other electric utilities in the U.S. do charge some fixed monthly fee for being hooked up to the electric grid.

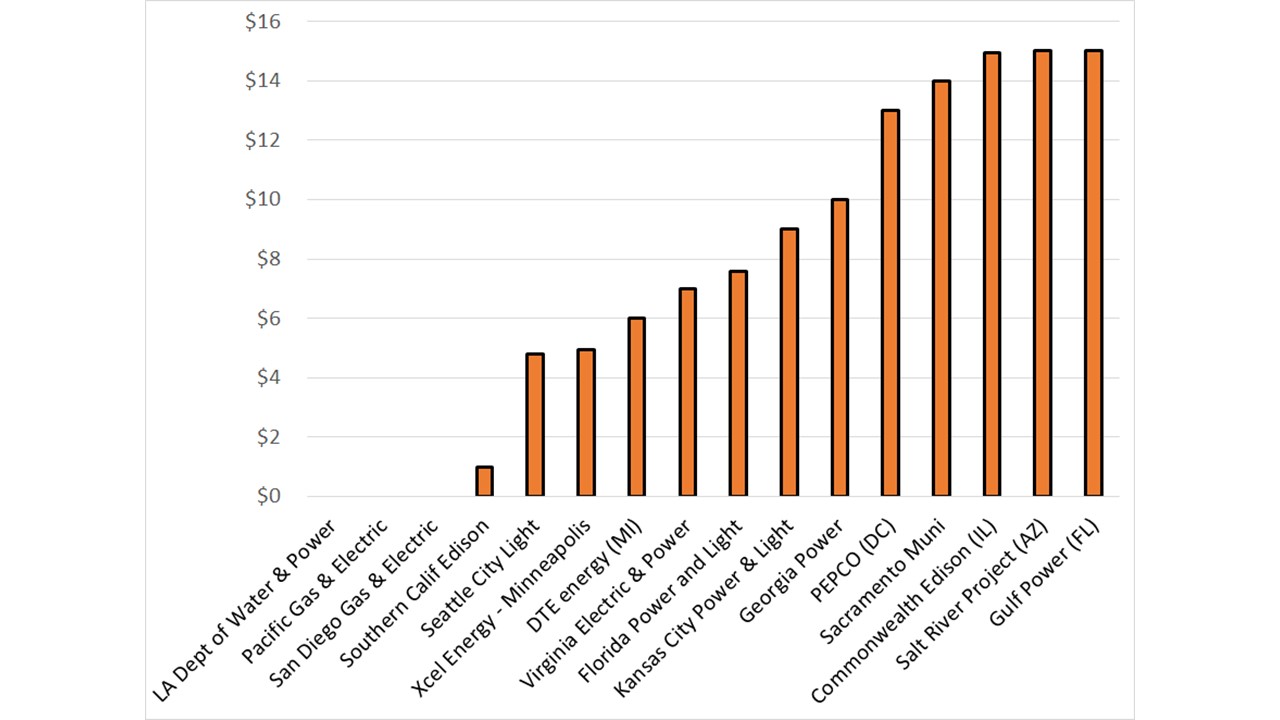

Fixed monthly charges at regulated and muni utilities (randomly selected outside CA)

Fixed monthly charges at regulated and muni utilities (randomly selected outside CA)

Fixed charges are often justified based on the utility having fixed costs. The connection seems logical at first glance, but when you look closer it’s more complicated.

Fixed costs fall roughly into two types: customer-specific and systemwide. When having one more customer on the system raises the utility’s costs regardless of how much the customer uses – for instance, for metering, billing, and maintaining the line from the distribution system to the house – then a fixed charge to reflect that additional fixed cost the customer imposes on the system makes perfect economic sense. The idea that each household has to cover its customer-specific fixed cost also has obvious appeal on ground of fairness or equity.

Customer-specific fixed costs from things like metering, billing, electric drop to house

Customer-specific fixed costs from things like metering, billing, electric drop to house

But much of the utility fixed costs that are being discussed are systemwide – such as maintaining the distribution networks in residential neighborhoods. These costs wouldn’t change if one customer were to drop off the system. In other words, running the system as a whole has certain unavoidable costs and someone has to pay them. There isn’t much guidance, based on economics or equity, about who should pay, because there is no “cost causation” as it is termed in the utility world. In particular, the statement I have heard a number of times recently that “the utility should cover fixed costs with fixed charges” has no basis in economics when it comes to system fixed costs.

Before we discuss how to pay for system fixed costs, let’s step back and remember where economics does provide a valuable guide, that is, in setting the price of an incremental or marginal kilowatt-hour. The price for a marginal kilowatt-hour should reflect the full “societal” marginal cost of providing that electricity, meaning that it should include the industry’s marginal production costs plus the marginal externality costs imposed on others outside the production process, like the cost of greenhouse gases that are released. The idea is that if you don’t place a value on the good that is at least as great as the full cost of producing it (including the pollution it creates), then society shouldn’t allocate resources to produce it for you.

If you don’t think about it too hard, you might conclude that if the marginal (or volumetric) price just covers marginal cost, then what is left over is fixed costs, so fixed charges “should” cover fixed costs.

But there are at least three good reasons to think harder about it.

First, the marginal cost that the utility faces is less than the full marginal cost it imposes on society when it produces electricity because the utility does not have to pay the full social cost of the pollution it produces — including NOx, particulates, and greenhouse gases.[2]

If the utility charges a price that covers the full marginal cost including all the externalities, but doesn’t itself actually have to pay for those externalities, then it generates extra revenue. That revenue can go towards covering fixed costs. That lowers the fixed charge necessary to cover costs while at the same time setting appropriate marginal prices.[3]

Second, as everyone who studies electricity markets knows (and even much of the energy media have grown to understand), the marginal cost of electricity generation goes up at higher-demand times, and all generation gets paid those high peak prices. That means extra revenue for the baseload plants above their lower marginal cost, and that revenue that can go to pay the fixed costs of those plants, as I discussed in a paper back in 1999.

The same argument goes for transmission lines, where price differentials between locations mean that the transmission line generates revenue above its marginal cost (which is effectively zero), and can go to pay the fixed costs of transmission lines. In fact, the fixed costs of generation and transmission should generally be covered without resorting to fixed monthly charges.

The same is not true, however, for distribution costs. Retail prices don’t rise at peak times and create extra revenue that covers fixed costs of distribution. That creates a revenue shortfall that has to be made up somewhere. Likewise, the cost of customer-specific fixed costs don’t get compensated in a system where the volumetric charge for electricity reflects its true marginal cost.

But unlike customer-specific fixed costs, there isn’t a strong fairness or economic efficiency argument for recovering fixed distribution costs – which are not customer-specific — through a fixed monthly charge.

Programs subsidizing high-efficiency light bulbs, refrigerators and washing machines may be a great idea, but they still create fixed costs that ratepayers have to cover

And then there are sunk losses from the mistakes of the past, such as expensive nuclear power plants and high-priced contracts signed during the California electricity crisis. And don’t forget ongoing expenses that are not directly part of the electric utility function, like energy efficiency. Someone has to pay for those subsidies on new refrigerators and clothes washers.[4]

That brings us to the third reason to think hard about fixed charges: fairness and distributional considerations. If customer A uses 10 times more electricity than customer B, should they pay the same share of the system fixed costs? And, by the way, customer A is on average wealthier than customer B. My informal poll suggests most people think customer A should pay more.

But any approach that is based on usage amounts to raising the volumetric price further, after we have already raised it to reflect the real externalities. Doing that encourages inefficient substitution away from electricity. Yes, there can be such a thing as too much energy efficiency investment (take a look at the cost of retrofitting windows). Nor does it really help society when high marginal prices incent households to install solar just to shift fixed costs to others. And, of course, Max recently blogged about how high marginal electricity prices discourage EVs.

And that’s where it can make sense to resort to fixed monthly charges to cover at least part of the shortfall. Fixed charges may be the least bad way for utilities to balance their books without setting volumetric electricity prices so high that they unreasonably distort behavior.

But the mere existence of systemwide fixed costs doesn’t justify fixed charges. We should get marginal prices right, including the externalities associated with electricity production. We should use fixed charges to cover customer-specific fixed costs. Beyond that, we should think hard about balancing economic efficiency versus fairness when we use additional fixed charges to help address revenue shortfalls.

I tweet energy news articles, and the occasional research article, nearly daily @BorensteinS

—————

[1] PG&E and SDG&E have no fixed charge, SCE’s is $0.99/month. All three have a small minimum bill, less than $10, which is binding on extremely few customers.

[2] What’s that you say? that California utilities already have to cover their GHG emissions in the state’s cap-and-trade market? Oh please. First, the utilities are given free permits to cover most of their emissions. Second, the regulatory agency (CPUC) has said publicly that it will not allow GHG costs to raise residential rates. And, finally, do you really think the current price in the cap-and-trade market of $12/ton – an amount that will lead to virtually zero change in production or consumption behavior — covers anything like the full cost of the GHG emissions? It’s less than one-third of the U.S. government’s estimate of the true externality cost (which I think is likely still too low).

[3] Of course, if we ever get to actually charging polluters for their emissions, then this source of extra revenue to the utility will go away. That will still be a happy day for me.

[4] Please, save the comments arguing that energy efficiency programs pay for themselves. They may save society as much or more in energy resource costs as they cost the utility, but when it comes to rate making, the money for those programs comes from ratepayers, and energy efficiency programs don’t justify a volumetric rate increase on economic grounds.

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Great article – it’s great to get folks thinking about this.

On your footnote #2, the “free” allocation of GHG allowances should be irrelevant, as they are based on historical (2008 I believe) emissions, and therefore are a fixed (sunk) benefit. The marginal GHG cost to IOU customers is still the market allowance price. Also, while the CPUC may moderate the impact on residential rates, the GHG costs are a pass-through to customers and would go to someone’s rates (usually settled in General Rate Case proceedings). Now, whether the allowance costs represent the true cost to society, what that cost should be, and why the market prices are lower.. is a good topic for another post from you! Either way, I think we should set electric rates assuming that the GHG price is right, and then fix the GHG allowance market if we believe it’s not working properly. I’ve actually heard the argument that some of the electric market regulations are depressing GHG prices.

On your second point, just a reminder that we don’t have hourly prices for customers. The rates are set based on an average marginal cost, among other considerations. In fact, at least in principle, they try to adress your concern: the fact that some fixed costs are per customer, while others are per kW/kWh. For example, when rates are allocated among customer classes, both capacity and energy marginal costs are considered – leading to different rates. (Of course, rate making is a complex process… and a lot more goes into it.).

In any case, I agree with your conclusion – we should think hard how to best balance proper economic incentives with fairness.

Disclaimer: while I’m employed by an IOU, the opinions above are my own.

I agree with the details you describe, but the case with water (as Janice mentions) may be different in some ways. It may be fine (efficient) to levy charges more or less in sync with their occurrence/variation, but it’s still good, in principle as well as in practice, to match charges to costs, to reduce fiscal instability. I also think your example (the marginal customer on the grid) is too narrow — it’s fine to load marginal costs on a group of customers, or even the group that calls on peak capacity (as Davis is trying to do with water).

But now a question: what’s the policy implication? No fixed charges? Only? three tariffs? Confusion?

Points well taken, Severin. I regard the fixed=fixed argument to be somewhat of a communication simplification, rather than a theoretical statement. Many of your points, such as the role of marginal prices in signaling consumption externalities, do come up in the periodic debates about efficient pricing, so you’ve nicely captured the debate. In a previous era, industrial prices were kept low to encourage attraction of new businesses to an area. One element missing from your blog is a reference to second-best (Ramsey) pricing, which leads to the well known inverse elasticity result. From this perspective, the bulk of the difference between average and marginal prices should fall to the fixed charge under the presumption that it is the least elastic rate component. Thus, it isn’t fixed=fixed, but rather fixed=residual. I’m not sure how much of a practical difference there is, however.

Here in MD, we have a small fixed rate (about $7.50 for residential), and of course they want more because of the increasing number of us who have rooftop solar. Here in MD they also seem to be moving away from the very slight time-of-day rate structure they had–yet it would seem those of us with solar should be getting credit for supplying energy to the grid during the peak demand times (and I must be doing this as I have had no usage charges during summer even though my AC is on) because one of the reasons for the subsidies for solar and efficiency steps was to avoid the cost of building a new tie-line from DC metro area to Ohio River Valley. But, in the discussions I hear about with utility execs talking about a higher fixed charge, I never hear about having realistic time-of-day buyback of solar, etc.–my guess is the two would offset, but they focus only on that side of the argument that would greatly benefit themselves.

One other point, I just saw the national statistics on energy sources for US electricity, and solar is small because all they count is utility solar and not rooftop solar. This gives a real misimpression.

This is essential reading for anyone engaged in this discussion for the energy and water sectors. From a theoretical view, I usually invoke the principle that in the long run, all costs are variable – so prices should reflect this. From a practical view, I like consideration of a three-part tariff (customer, capacity, and commodity), with variable capacity charges based on relevant economic and policy criteria, including equity. For water, high fixed charges will seriously undermine potential efficiency to be found in reducing discretionary outdoor usage and thwart opportunities to re-optimize systems and avoid both capital and operating costs. And over time, efficient usage of water and energy should lead to relative stability in bills and revenues to the benefit of both ratepayers and utilities.

As you well know, much of the “fixed” costs for distribution are “common” costs that need to be recovered in some way, but unclear how to do so. Fred Kahn used to say that “allocating common costs is like trying to find a black cat in a dark room. [pause] Where there is no cat.”

The commercial customers rates at most utilities use a Demand Charge which communicates a variety of costs to the customer, and compensates for the capital costs that are driven by the level of demand. A PV-using customer may have a net zero in energy, but a Demand Charge would capture the use at night. This on-going practice seems little mentioned in this debate.

Where there is a potential for the utility to be ‘called in’ IF there is a problem there should be a fixed charge, or a ‘service call’ charge. Net metering rates should be based on the marginal cost [to the utility] of production at ‘that time’; there should be a transmission-distribution cost adjustment to the net meter rate. The charge for the societal cost of energy consumption should not be part of the rate, but a tax imposed on the consumer, and paid to the ‘state’ [collected with the utility bill]; this ‘societal cost’ tax should be based on the ‘average’ of GHG etc for the utility. I dont have the economics basis for these ‘suggestions’ but do have the behavioral foundation to support them.

Re: the water bill example given by David Jacobowitz: that can quite easily be fixed by having a steep usage-based tier rate. The water utility I am connected to has such a structure [billed every other month, unit=748gallons]: connection charge $50, usage [about] $3/unit for first 10 units, $4/unit for the next 15 units, $7/unit for the next 25units, and $11/ unit for anything over 50units in a two month period.

There are “fixed charges” and then there are “semi-fixed charges.” When I get my bill for my cell phone, most of the charge is fixed, very little is variable based on the amount of content. But the fixed portion is not really fixed, it is determined by the plan I have and how much content I want to download, especially how fast I want to be able to download content. So the “fixed charge” for my cell phone is “semi-fixed.”

A difference between telecommunications and power is that electric utilities routinely measure the speed with which customers take electricity, using the term demand. Since economists use “demand” in a different context and are more numerous than power engineers, let’s use the term download speed, such as could also be used to described the communications system.

Any payment for demand or download speed could also be considered to be a fixed charge, or semi-fixed charge. A demand charge would separate out the functional difference between generation and transmission providers, for which we have established competitive markets through our ISOs and RTOs. A demand charge would be fixed and recover the fixed costs of the distribution utility (and some generation and transmission costs for those utilities that are still vertically integrated.) Customers want the connectivity associated with distribution wires. So let’s collect based on a measurement to is proportional to the customers’ wants, demand.

For more on this concept of a demand charge, see my “Curing the Death Spiral,” with Lori Cifuentes (Tampa Electric Company), Public Utilities Fortnightly, 2014 August.

https://www.fortnightly.com/fortnightly/2014/08/curing-death-spiral?authkey=54d8da5efd3f76661023d122f3e538b4b3db8c8d5bf97a65bc58a3dd55bb8672

or my upcoming “Demand a Better Utility Charge During Era of Renewables: Getting Renewable Incentives Correct With Residential Demand Charges,” Dialogue, United States Association for Energy Economics, 2015 January, http://dialog.usaee.org/index.php/volume-23-number-1-2015/271-lively

I don’t have anything to add about how rates *should* be structured but other markets with low/zero marginal cost commodities may be a guide to what we can expect from future rates:

water: residentially at least, a huge fixed charge dominates the bill. I know this because we reduced our water usage by more than half over last year and received meager savings in return for the destruction of our garden. 😦

internet: residential, 100% fixed charge

mobile telephony: 100% fixed charge

wired telephony: haven’t had a POTS line in awhile, but last I did, the industry had lurched strongly towards fixed charges and very low /minute rates.

As electricity moves towards renewables, with their high up front and low marginal costs, its hard to imagine electric power bucking this trend.

On the other hand, media, with actual zero marginal costs, and which has been settled on fixed charges for eons (you buy a CD or DVD, you subscribe to the NYT, etc) seems to at least frequently dabble with per-performance pricing. Who knows where that will land?

All that said. I do have an anecdote to offer: I have a family member who lives in a jurisdiction where the local utility (publicly owned!) is pushing to add a large fixed charge to net-metered PV customers’ bills. The charge appears to be set more or less perfectly to zero out any benefit to the average net-metered customer over and above the wholesale energy value, which is quite low in this particular southwestern coal state. Without getting into a debate about whether net metering is “good,” it’s clear that large fixed charges can be a cudgel against EE, DR, and self gen activity.