Clean Energy Tax Credit Concerns

Credits for heat pumps, EVs and solar panels still go mostly to the wealthy.

Over the last two decades, U.S. households have received $47 billion in federal income tax credits for buying heat pumps, solar panels, electric vehicles and other clean energy technologies.

In a new Energy Institute working paper, Severin Borenstein and I use tax return data from the IRS to examine which households get these credits and how that has changed over time.

We studied these questions about a decade ago, but we think now is an opportune time to revisit the topic. Last year was the warmest year on record, and rising temperatures and other climate impacts are spurring policymakers to introduce and expand subsidies like these to help transition markets away from fossil fuels.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, the tax credit for heat pumps increased last year from $300 to $2000. The IRA is interesting also because it includes maximum income limits and other features designed to change who is eligible for these credits. Our data cover 2006-2021 so we are not yet able to look directly at the IRA, but we can shed light on the period leading up to it.

—

High-Income Filers

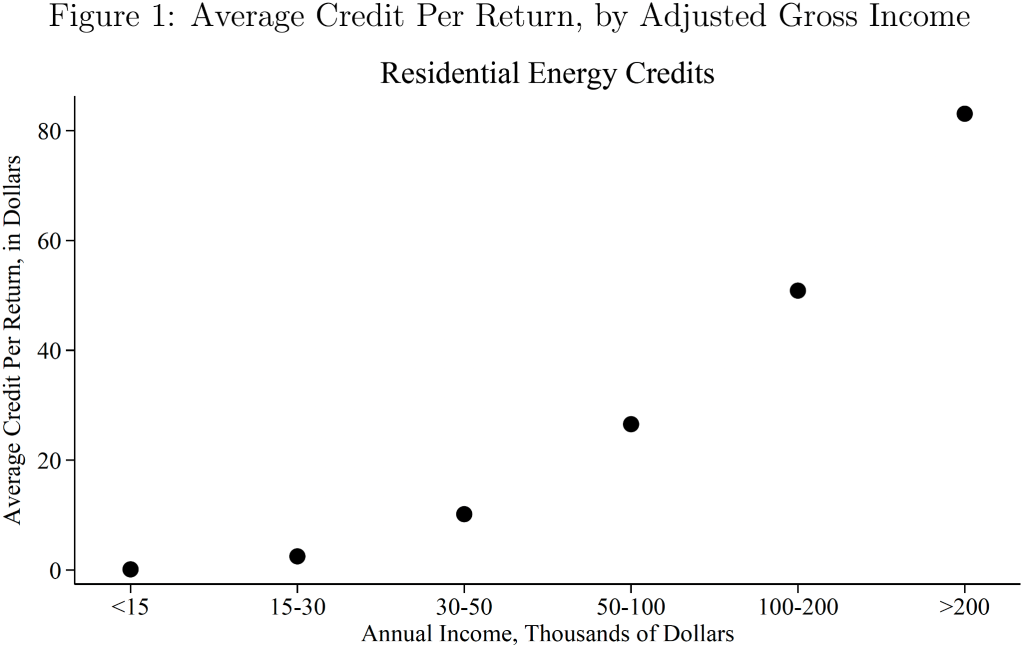

We find that clean energy tax credits have gone predominantly to higher-income filers. The figure below divides filers into six categories based on their adjusted gross income. The first four categories are approximately quintiles and then the last two categories together make up the top quintile.

—

For a broad set of residential energy tax credits, the bottom three income quintiles received 10% of all credits while the top quintile received 60%. The figure above reflects the entire time period 2006-2021 and includes two major categories of tax credits: (1) energy efficiency investments including , for example, windows, doors, and heat pumps, and (2) residential solar.

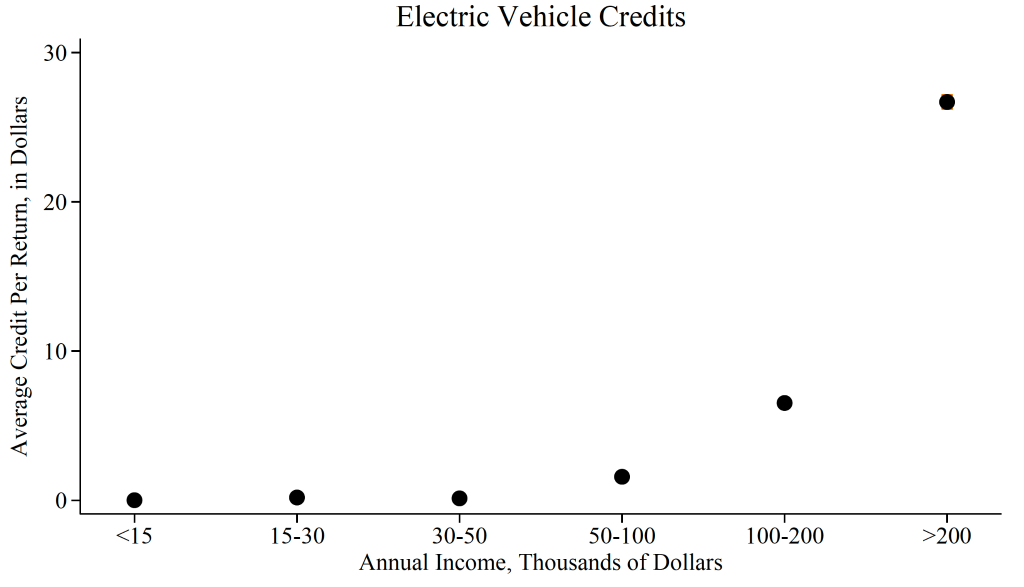

Even more extreme is the tax credit for EVs.

—

As the figure above illustrates, the average credit per return – which accounts for both the size of the credit and the share of returns that claim it – was less than $2 for filers with income below $100,000, $9 for filers with income $100,000-$200,000, and then $27 for filers with income above $200,000. Overall, the top quintile received more than 80% of all EV tax credits.

—

Time After Time

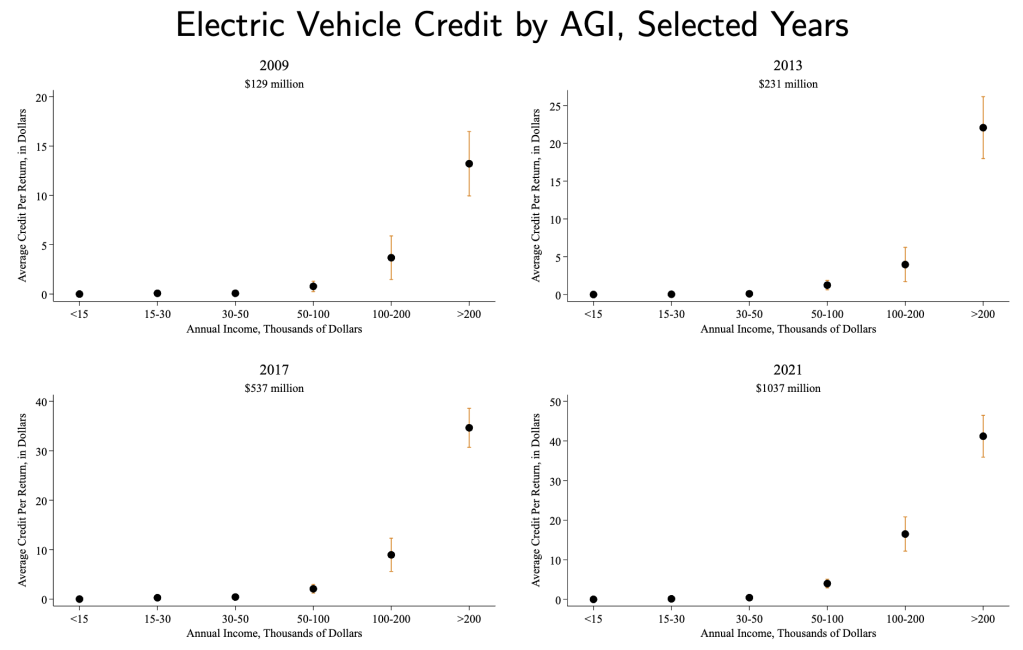

But how has this changed over time? Rather than combining all the years together, the figure below shows the pattern for individual years at four-year intervals.

—

We find that, year after year, the pattern is the same. Across all 16 years in our data, we find that 60% of residential energy credits go to the top income quintile. Relative to a similar analysis that we conducted about a decade ago, we’ve added nine additional years of data, yet the overall pattern of distributional effects is almost exactly the same.

The distributional pattern for EV credits is also very similar across years. See the figure below. Across all years, we find that 80%+ of EV tax credits go to the top income quintile.

—

This lack of change over time is somewhat surprising. The markets for heat pumps, solar panels, and EVs have matured substantially over this time period. With EVs, we’ve gone from only two models being available to more than 100 models being available today. With residential solar, total U.S. capacity has increased more than 50-fold. Despite all these changes, we see little evidence of a broadening across the income distribution.

—

What About Leases?

One disadvantage of working with household tax return data is that they do not include tax credits from leases. This is a major share of the market for EVs and residential solar, though not really relevant to heat pumps or most types of energy-efficiency investments.

When a household leases an EV or solar panels, the lessor (e.g. Tesla or Sunrun) is able to claim the tax credit, but the household is not. In order to get a sense of how leasing could be influencing our results we compiled data on how lease shares have changed over time.

—

Interestingly, the lease shares have fluctuated significantly over time. But while the lease share has been going up and down, the concentration of these tax credits among high-income filers hasn’t budged. This suggests that leasing is unlikely to be substantially biasing our distributional analysis.

—

Mechanism

Why do tax credits go predominantly to high-income households?

Part of the explanation is that all of these credits are non-refundable. About 40% of U.S. households pay no federal income tax, so millions of mostly low- and middle-income filers are simply ineligible for these credits. We don’t think there is a good argument for making these credits non-refundable. The objective of these tax credits is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. From this perspective, there is no difference between filers with positive and negative tax liability, so this asymmetric treatment does not make sense.

Another part of the explanation is that neither renters or landlords are eligible for the tax credits aimed at heat pumps and other energy-efficient investments. Over one-third of U.S. homes are rented, so this is a significant omission and another highly asymmetric treatment that is hard to rationalize from a greenhouse gas perspective.

In future work it is going to be very interesting to see if and how these patterns change with the IRA. One of the biggest changes is a move toward point-of-sale subsidies. Starting in 2024, for example, the tax credit for EVs has been available at the point-of-sale. There are also new maximum income requirements for EV purchases (though not for leases) and other design features specifically designed to address who gets these credits. These are potentially quite significant changes so stay tuned.

—

The Takeaway

So, are clean energy tax credits a good idea? Ultimately, in evaluating tax credits or any public policy it makes sense to think about both equity and efficiency. Our new paper is mostly about equity and mostly bad news, with the lion’s share of these tax credits still going to higher income households.

What about efficiency? Although tax credits may initially seem like a good idea, they have several serious limitations relative to first-best policies like a carbon tax. Perhaps most importantly, tax credits don’t help achieve the efficient level of usage. Take passenger vehicles for example. A tax credit can encourage households to buy an EV, but it cannot get people to drive less, or take public transportation, or to ride a bike. A carbon tax, in contrast, would encourage people to reduce gasoline consumption along all margins.

Then there is the question of how much tax credits change household behavior, i.e., how many additional purchases of these clean energy devices they create. Unfortunately, many recipients receiving the tax credit would have made the purchase regardless. Our paper presents some suggestive evidence (more on this in a future blog post), but understanding adoption behavior better is a key priority for future work.

Tax credits are also extremely coarse instruments. The amount of carbon abatement achieved with a heat pump space heater depends on how cold it is where you live, the size and thermal efficiency of your home, and on what type of heating you would use otherwise. A carbon tax, for example, would create stronger incentives in places where heating is more important, but none of this can be reflected with a single nationwide uniform subsidy.

Probably the biggest advantage of tax credits is political palatability. I don’t pretend to understand what is possible or not possible politically, but I do think it is worth recognizing that the U.S. preference for “subsidize green” over “tax brown” comes at a high cost in terms of economic efficiency. Moreover, the distributional impacts are a real concern. Through several key features of the tax code, we have set up these credits in a way that tilts the benefits towards the highest-income households.

—

—

For more see, Borenstein, Severin and Davis, Lucas. “The Distributional Effects of U.S. Tax Credits for Heat Pumps, Solar Panels, and Electric Vehicles” Energy Institute Working Paper, (June 2024), WP-348.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Clean Energy Tax Credit Concerns” Energy Institute Blog, June 17, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/06/17/clean-energy-tax-credit-concerns/

—

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

—

By default comments are displayed as anonymous, but if you are comfortable doing so, we encourage you to sign your comments.

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

We need to invest trillions of dollars to accelerate technology investments for climate action. So we can create incentives to accelerate those investments, or we can keep obsessing about “equity” concerns. Pick one. You cannot have both. Because every action we take in the name of some equity concern only makes it harder and more time consuming to get the necessary climate action. Sorry to break that news. Welcome to the real world.

I’m shocked, shocked! that those who actually pay income tax are the ones taking advantage of income tax credits, not the 40% of the population who don’t pay income tax — the lower income and highest income citizens.

And what a surprise that those well off enough to own greenhouse gas emitting furnaces are the only ones taking advantage of a program to replace them.

But the lower income people bear the brunt of the cost – in higher unit prices when the higher income folks 1: take the credit, and 2: reduce usage so the rest-of-us have a higher burden of the fixed costs. ‘You’ still use the roads, and have access to the grid, but carry a much lower share of the fixed load. ALL rebates should be DIRECT payments, not tax credits. DO NOT mix social policy with tax policy.

“DO NOT mix social policy with tax policy.” Best quote yet on CPUC choices that push social issues financial cost onto us working people who “pay our utility bills or get our power cut.”

I bought a new car last year. I’m over the income limit for the tax credit. The price difference between gasoline and EV didn’t make sense without it, especially given EV performance issues in winter (I live in a colder state than California). I bought a gasoline car instead of the EV. EV sales growth has stalled recently, which is odd given the supportive policy of, uh, effectively imposing a tax on the most likely EV purchasers (higher income people). Ok, you can debate the precise allocation between buyer and seller of the credit, and degree to which it is a tax (i.e. the credit is captured by seller, thus absence serves as a tax), but the fact that we’re having this debate is really brilliant policy!

This seems like the not the most insightful research. Richer people waste money on inefficiently energy efficient toys. Rooftop solar is a hideously inefficient way to reduce carbon, as this blog has pointed out numerous times, though the virtual signaling value is par excellence, so there’s that. In other news, richer people also tend to purchase more Chateau Margaux, new iPhones, and take more Colorado ski trips. I’ll volunteer to do the field work.

In retirement, I am unable to use big tax credits in most years. The EV “assignable” tax credit for EVs is a useful solution for me. No surprise that most heat pump credits go to the top quintile. They can afford high cost capital investments.

Jim Lazar

Thanks for this! Insightful, provocative, and timely.

While I think it is likely outside the scope of this paper, I am very curious about linked rate equity issues. Does it follow from this Energy Institute at Haas paper that low and medium-income customers/ratepayers (largely non-adopters of roof-top solar) are funding a disproportional share of the credit that solar adopters (mostly higher income customers/ratepayers) receive for their roof-top solar generated electricity? From my vantage point, the NEM 3.0 battle and subsequent litigation pivots around this issue.

I look forward to reading the entire working paper!

Jim Dodenhoff

There does not seem to be anyplace to leave comments on today’s blog on subsidies.

Regards, Robert Archer ________________________________

The Trueth is out there. Solar and other GREEN technologies cost lots of money and only the people with FAT bank accounts can afford to buy any of these things. This is why the Government targeted them to get Tax Credits since they are in higher tax brackets to begin with and are looking for any breaks they can get. The education “refundable” Tax credits can go to low income Houshold’s and be partly or fully refundable even if no Federal tax is due. Why is education valued higher than solar? Because it is more important to help people more earn higher “Taxable Income”. Utilities also have “Skin in the game” and do not want the masses to produce their own energy putting utility companies out of business. NEM3.0 is a good example of how Utilities along with the Government (CPUC) want to keep energy production in the hands of Big Utilities and out of the hands of the “Voters” that do not contribute to the re-election of the “status Quo” while utilities are BIG contributors to politicians. The GAME is rigged against those living paycheck to paycheck. Great article.

Perhaps the most important overlooked aspect in this blog is that the wealthy dominate the early adopters of any new technology, particularly those that are more expensive. Automobiles, refrigerators, TVs, and cell phones are just a few examples. The wealthy are more willing to buy these because they can afford to be less risk averse. If a product fails, they have more resources to overcome that failure with an alternative means and can afford more easily to buy a replacement. The problems with access to charging infrastructure for EVs is an example for the current wave to technologies. So of course any subsidy aimed at a specific technology will be dominated by higher income consumers.

As for effectiveness of these policies, I don’t see how any of these products would have been purchased at the same level without the credits. Are you saying that there’s no consumer price elasticity for high income consumers when a products is discounted by several thousand dollars? That runs directly opposite to the assertion that a carbon tax, which relies entirely on consumer price response, would be more efficient. (It’s also ironic that the IGFC proposal was justified on the basis that it would incentivize electrification but in fact those types of purchases are less than 5% of electricity use so the IGFC has an even larger policy leakage.) Either prices matter in all situations or they don’t matter at all.

As for the efficiency of a carbon tax over a tax subsidy, wasn’t there a recent Energy Institute blog (by a different author) questioning this orthodoxy? Carbon taxes might subtly move market behavior over time, but it’s not obvious that they need to be less efficient. Subsidies like tax credits can be viewed inversely as direct payments to quasi-suppliers (who are also consumers) to make investment decisions. And because these subsidies go to a small portion of that supplier market instead of raising energy prices for everyone, they might lead to a smaller transfer in consumer surplus to producers.

All that said, the limitations on applicability of the credits, particularly to rental properties, is a huge problem. We can hope that the IRA provisions will go a long ways towards solving this inequity.

“As for effectiveness of these policies, I don’t see how any of these products would have been purchased at the same level without the credits.”

Yes, it is true that credits will be the deciding factor in some of these purchases, but the question is: how many? If the answer is relatively few, then it’s almost certainly not a worthwhile.

“Either prices matter in all situations or they don’t matter at all.”

Prices certainly do matter in (almost) all situations, but they matter more in some than others. Yes, that can easily lend itself to more subjective analytics, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

Kurt Schuparra

Kurt

The assertion here is that a carbon tax could be effective in moving significant purchases of EVs, HPs and solar panels. Yet, the contrary assertion is that subsidies through tax credits have not moved significant purchases in EVs, HPs and solar panels. Those two concepts cannot coexist. Again, either prices matter for everything, or they matter for nothing. And they matter largely the same in most situations–the burden of proof is on those who claim that the effect differs. (But as I pointed out, I believe there was an earlier blog post that pointed out that subsidies appear to have been more effective.)

If, as you point out, that prices–reflected in carbon taxes or tax credits–makes relatively little difference but we need to rapidly accelerate adoption of specific technologies, then we have to move to mandates (e.g., 100% EV sales by 2035).

I am more interested in reading the comments than in leaving a comment.

Thank You. The more points of view we can see, the perspective we have on a subject. Keep Reading.

Let’s look at this from another perspective. The goal is to reduce carbon emissions. Even if you don’t believe that climate change is an existential threat, the future is really going to suck for humanity and 80% of the other species on earth. So discussion which method to employ to reduce emissions is ridiculous, we should be doing everything we can. Not a) or b) or c) but d) all of the above. Even if they are not cost effective because, “there are not pockets in a shroud.”

-OSD