It just doesn’t add up. Why I think not building Keystone XL will likely leave a billion barrels worth of bitumen in the ground.

I am not a fan of blanket statements. Whenever oil sands come up in casual conversation, many of my economist friends argue that “the stuff will come out of the ground whether we like it or not”. When the discussion turns to Keystone XL, the general attitude is that “it simply doesn’t matter. The Canadians are just going to build pipelines to the East and West and ship the stuff to Asia and elsewhere.” So I started reading and learned a number of interesting things (which I have written up in more detail here).

Alberta’s oil sand reserves are estimated at 168.7 billion barrels, which eclipses the reserves of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Russia. What makes these reserves different from those in Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and the countries named above is that they are in the form of crude bitumen. As has been discussed widely, the mining, upgrading, transport and refining of this resource is very energy intensive. As a consequence, well to wheel emissions from these oil sands are 14-20% higher than those of a weighted average of transportation fuels used in the United States.

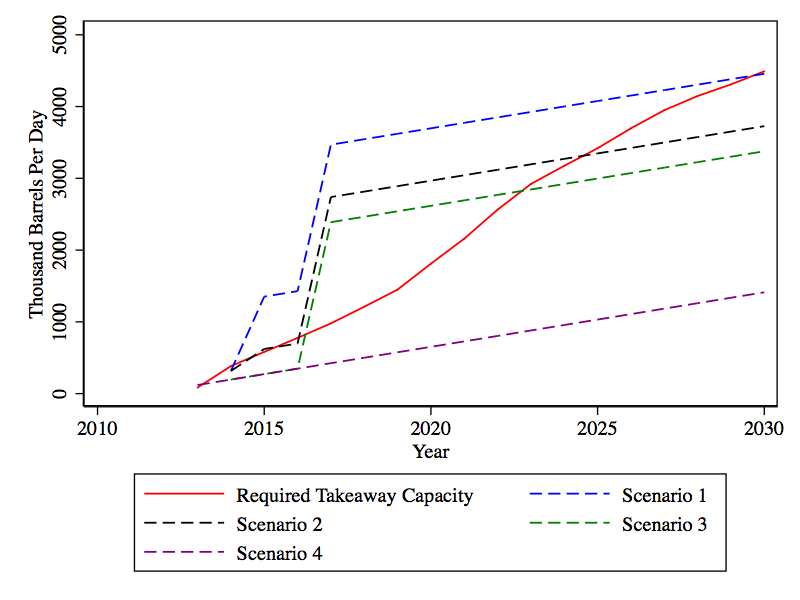

The problem the owners of this precious resource have is that there simply so much of it and currently there is nowhere near enough transport capacity to get the desired number of barrels to refineries. This is not news. What I argue below, however, is that even if every pipeline project on record is built on time and rail capacity is expanded aggressively, there still is not enough transport capacity to meet industry projected supply. This means, of course, that Keystone XL matters in terms of how much of the oil sands will be extracted over the next 26 years (the “official” time horizon adopted by the State Department). I think that even under the best-case scenario in terms of supply, where all other pipeline projects are approved and built, not permitting Keystone XL will likely leave 1 billion barrels in the ground by 2030. If other projects are not built, Keystone become marginal earlier and that number becomes even bigger. Now on to the pesky details.

Projected Supply and Capacity

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, an industry alliance, anticipates rapid growth in the production of oil sands until 2030. According to their projections the supply of total crude, both heavy and light, will grow from 3.438 million barrels per day (mbpd) to 7.846 mbpd. 97% of this growth is projected to be due to the development of oil sands. This represents a 3.8 fold increase in the supply of oil sands compared to today.

As local refinery capacity is severely limited (Goldman Sachs, 2013), the majority of the additional industry projected 4.285 mbpd by 2030 have to be shipped out of Northern Alberta. This can be done by pipeline to the West, East or South or surface transport (rail or barge). Pipelines are the least expensive mode of transportation and allow the shipment of both light and heavy crude. Goldman Sachs estimated total takeaway capacity via pipeline at 2.9 mbpd in 2013 plus another 0.454 mbpd of local refining capacity. Currently estimated rail capacity to the US is 150,000 bpd and could reach 500,000 bpd by 2017/8. Therefore the required additional takeaway or local refining capacity in 2030 will be 4.492 mbpd.

In order to meet this demand, several pipeline projects have been proposed, which I list below with their proposed starting dates and capacities as provided by Goldman Sachs:

- Alberta Clipper 1 (2014): 0.120 mbpd

- Alberta Clipper 2 (2015): 0.230 mbpd

- Keystone XL (2015): 0.830 mbpd

- Northern Gateway (2017): 0.525 mbpd

- Energy East (2017): 0.850 mbpd

- Transmountain (2017): 0.590 mbpd

Each one of these projects is facing regulatory hurdles and it is not clear that any of these projects will be approved with certainty. I would like to consider the following three scenarios:

1. All pipelines get built, rail capacity is ramped up to 500,000 bpd by 2018 and continues to grow by 76,000 bpd per year thereafter.

2. All pipelines except Keystone XL get built, rail capacity is ramped up to 500,000 bpd by 2018 and continues to grow by 76,000 bpd per year thereafter.

3. All pipelines except Keystone XL, Alberta Clipper 1 & 2 get built, rail capacity is ramped up to 500,000 bpd by 2018 and continues to grow by 76,000 bpd per year thereafter.

4. No pipelines get built, rail capacity is ramped up to 500,000 bpd by 2018 and continues to grow by 76,000 bpd per year thereafter.

The figure above plots available takeaway capacity for each of the scenarios against projected takeaway need. The first thing to note is that the only scenario that provides sufficient takeaway capacity to get the 2030 level of producer projected bitumen out of Alberta is scenario 1, which assumes that all proposed projects get approved and rail capacity is aggressively built out. This scenario also has plenty of spare capacity until 2030 and would minimize the need for railway transport until the end of the period. Scenario 2, which is a world sans Keystone XL, has plenty of capacity until 2024, which is when both high and low cost transport modes are filled to capacity. At this point, there is no currently proposed pathway, which would be able to ship out the difference between the red line and the black dotted line as of 2024. The total amount of this triangle is roughly one billion barrels that would “stay in the ground” by 2030 – assuming no additional projects. For scenario 3, which is the green dotted line, producers run out of shipping capacity by 2023 and the missing capacity results in 1.9 billion barrels remaining in the ground. If none of the pipelines get built within and out of Canada and one has to rely on this rail scenario, capacity would run out this year and roughly 10 billion barrels stay in the ground. The last scenario would require that all pipeline projects are denied and no alternate projects proposed and granted. What is noteworthy about the last scenario, is that if no pipelines get built, rail does not provide sufficient capacity to meet projected takeaway demand in the short run. Not building Keystone XL would make the rail capacity constraint binding and therefore lead to slower extraction even in the short run.

Other factors affecting investment in tar sands

As discussed in the previous section, the first factor which will slow development of oil sands in the absence of Keystone is the fact that according to the scenarios I describe above, there is simply not sufficient transport capacity to realize the supply projections by Canadian Petroleum Producers out to 2030 even if all other projects are built and rail capacity grows most rapidly. It is important to note that this argument is independent of the marginal cost of resource extraction, which is addressed by a variety of other reports.

The second factor has to do with regulatory uncertainty. As none of the projects so far have been approved and as it is less than certain that the Northern Gateway or any of the other projects will gain regulatory approval, large-scale investments in oil sands extraction remain a risky investment. The path forward does not look to be a smooth one for many of these projects, largely due to local and regional resistance and multiple court challenges. Goldman Sachs has in the past downgraded the resource for this reason.

The third factor, which is of key importance, is that currently oil sands enjoy an unfair advantage as they are a very carbon intensive form of transportation fuel. In the absence of a carbon tax or other price based mechanism, its price is artificially lower than socially optimal. Should a global or US only life cycle analysis (LCA) based carbon tax emerge in the next decade, this will decrease the price per barrel received by producers of oil sands and lower their profit margins. An LCA based carbon tax would also mean that product shipped via rail would carry a higher penalty than product carried via pipeline. Building Keystone would therefore provide oil sands with an advantage – even in a world with a carbon tax. All of this again would lower returns to investment in oil sands development.

Fourth, the future demand for petroleum based transportation fuels depends heavily on the availability and cost competitiveness of renewable low carbon alternatives and overall demand. Fuel efficiency regulations, which are already on the books, and further tightening of these standards will shift in the demand for transportation fuels. More competitive renewables will further shift in the demand for fossil transportation fuels. While it is not clear whether these alternative fuels will become cost competitive by 2030, delaying extraction of oil sands now will lead to lower demand in the future.

The fifth factor is related to environmental regulation of rail transport. Shipping crude oil, be it heavy or light, by rail is risky as accidents have significant environmental and economic costs associated with them. A significant increase in rail transport (in our scenario an 11 fold increase from today) would likely result in increased safety and environmental regulation, which would further drive up the costs of rail transport. Higher transport costs by rail would result in lower profit margins, since in my calculations rail is used fully in all scenarios.

Finally, the one factor that is uncertain is the very costly development of local refining capacity in Alberta. The refined product would still have to find its way to market and this is done by pipeline or rail, which we show is significantly constrained already.

Final Thoughts

If we use these industry projections on light, medium and heavy crude oil supply out of Western Canada, my calculations suggest that in order to be able to ship projected supply by 2030 all proposed pipeline projects have to be built, along with a significant increase in rail transport. My calculations suggest that not permitting Keystone XL will result in a binding transport constraint by 2024 at the very latest. If all planned pipeline projects are significantly delayed, not permitting Keystone XL will very likely reduce production in the short run and continue to do so unless additional pipeline capacity comes online, which is less than certain. While this post does not conduct an oil industry wide equilibrium analysis, it suggests that not permitting Keystone XL to proceed will keep a minimum of one billion barrels of heavy crude from Canadian bitumen in the ground by 2030 – in the absence of additional transport or refining projects. Of course, globally speaking, 1 billion barrels sounds like a lot, but the US consumes that amount in about 50 days.

As carbon is a stock pollutant as far as human time frames are concerned, not permitting Keystone “buys time” for alternative transportation fuels and climate policies to develop. This would allow all transportation fuels to compete on a level playing field, where carbon is taxed at its marginal external cost, which is a comprehensive policy solution. Trying to cure this large-scale burn with thousands of Band-Aids is simply not an efficient approach.

Categories

Maximilian Auffhammer View All

Maximilian Auffhammer is the George Pardee Professor of International Sustainable Development at the University of California Berkeley. His fields of expertise are environmental and energy economics, with a specific focus on the impacts and regulation of climate change and air pollution.

1 bn barrels = 11 days of global consumption.

I don’t know why you’d put all your political capital into such a marginal issue.

Is leaving the bitumen in the ground in the best interests of everyone? Let’s face it: oil is the most efficiently stored and exploited form of energy, and our hunger for this form of energy is limitless, except for that its supply is theoretically limited. Don’t we get more out of these sands by leaving them alone and vesting for 10-20 more years? If we don’t get more because far more efficient alternatives are invented between now and then, well, then isn’t it a win that we left it in the ground? Otherwise, we’ve committed businesses to extract all of it for the profit, when there are much better alternatives “down the pipe”.

To me, it seems there is a very simple reason we know that the tar sands oil companies cannot get all that oil out of the ground without the XL pipeline: They are fighting so hard to get it built. The pipeline has been on hold for years now, and still they are fighting and lobbying for it. If they really could move the oil without it, they would have put the alternatives in place by now. We don’t need to do all those calculations to prove that they need the pipeline to move that oil. They have obviously done it for us.

Hi Max. Your piece is certainly thought provoking but there are a number of factual errors and dubious assumptions that need correction.

1) The proposed Keystone XL pipeline, similar to the many other pipelines connecting the U.S. to Canadian oil supplies, would carry many different types of Canadian oil as well as some U.S. crude oil. This includes conventional Canadian light and heavy oil and U.S and Canadian unconventional oil (U.S, Bakken light, synthetic crude oil, and various mixtures of diluent and bitumen (dilbit), mixtures of synthetic and bitumen (synbit) and mixtures of conventional oil and bitumen). It does not seem reasonable to decide whether a such a pipeline would or would not be in the US public interest based simply on the life cycle emissions for just one (oil sands-derived) type of oil that the pipeline would carry and greatly exaggerated claims about the carbon implications.

2) The assumption that the Canadian oil that would flow on Keystone XL would all be oil sands-derived oil with well to wheel carbon emissions “14-20% higher than those of a weighted average of transportation fuels used in the U.S.” is not credible. In fact, even if the pipeline only transported Canadian oil sands-derived oil, the life cycle carbon emissions would be something in the order of 6% above the average for crude oil supplies to U.S. refineries. Further, as indicated by various life cycle analyses (for example, see http://www.api.org/aboutoilgas/oilsands/upload/cera_oil_sands_ghgs_us_oil_supply.pdf ) the well to wheel emissions associated with Canadian oil sands-derived oil is well below that for Venezuelan and other heavy oil imported to the U.S. and and well below that of U.S. heavy oil such Kern River production that meets a large percentage of California’s oil requirements. Given their larger carbon footprint, imports of Venezuelan and other non-Canadian heavy oil to supply the large U.S. Gulf Coast refinery demands would be displaced by increased flows of Canadian heavy oils moving on Keystone XL and this would tend to reduce rather than increase carbon emissions associated with U.S. transportation fuel supplies. Further, given the very high capital and energy intensity and widespread flaring associated with rapidly growing U.S. supplies from the Bakken formation, that production would also have a very high carbon footprint that is certainly much higher than that for many types of oil sands-derived oil. It can be noted that some of the oil sands production involves cogeneration that displaces coal-fired electricity generation and as such generates well to wheel carbon emissions significantly lower than the average for oil production. Also, there have been rapid technological improvements in the oil sands industry that have and will continue to drive down emissions. For example, between 1990 and 2009, the GHGs per barrel of oil sands-derived oil declined by about 30%.

3) You argue that currently the oil sands enjoy an unfair advantage because it is a very carbon intensive form of transportation fuel and is not subject to a carbon tax. However, the fact is that Canadian oil sands producers face a carbon levy of $15 per tonne of carbon emitted based on a binding emissions constraint that is reduced each year. There is no such price on carbon emitted by U.S. producers or on non-Canadian oil imported by the U.S. This levy, set by the Government of Alberta, is expected to be raised substantially in the near future so if anything one could argue that from a carbon tax vantage point the oil sands enjoys a significant and growing unfair disadvantage rather than an advantage.

4) In essence, your argument seems to be that if you can kill Keystone XL, you will be able to kill off growth in oil sands production and thereby dramatically reduce carbon emissions. But, some perspective is in order. Even if you shut down the entire oil sands industry the reduction in emissions would be less than 1/40th of the annual carbon emissions associated with coal fired electricity plants in the U.S. Further, it is not reasonable to argue that if US imports of Canadian oil were curtailed by killing Keystone, this would make any difference to U.S. or world oil consumption. To the extent your strategy of curbing Canadian oil production through killing Keystone XL would be successful, the only significant impact is that the U.S. would become more dependent on non-Canadian oil imports. Whether that is better for the U.S. is another worthy conversation.

What Dr. Mansell didn’t mention, is that his primary public argument in favor of pipelines carrying Canadian oil has been that pipelines are the only way Canada can access lucrative developing markets, like Asia, especially during a time when the US is producing more of its own domestic oil.

His opinions appear frequently on the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association’s blog. Here is an example:

http://www.cepa.com/canadas-export-business-why-we-need-pipelines-to-access-world-markets

It is hard to understand how he can say that “To the extent that the lack of capacity impairs the ability of [the oil and gas industry] to prosper and has very substantial negative impacts on the overall economy” and that “we have no other way of getting to tidewater [to access foreign markets] but through pipelines” without also making the case that the Keystone XL will have a material impact on the quantity of tar sands brought to market. Which is to say that he has come perilously close to corroborating Dr. Auffhammer’s analysis in other venues.

He further undermines his argument by “correcting” the estimate, made by the US Congressional Research Service, that tar sands well to wheel emissions are 14-20% higher than the US average, by citing a report by energy industry consultants CERA hosted by the American Petroleum Institute and by failing to mention that Canada’s oil and gas industry strongly supported the modest carbon tax he points to specifically because of its public relations value in venues like this one.

Dr. Mansell may be an otherwise fine economist, but his post in this context is nothing but advocacy.

Thanks Sam, I quickly spotted that he found and, it looks like, exaggerated every pro-KXL claim, and minimized or ignored every anti-KXL claim. Just advocacy – and an economist who can be paid to do that, in such a one-sided manner, isn’t a fine one, no matter how skilled.

Max has provided a thoughtful and thought provoking analysis of bottlenecks in accessing the Alberta Tar Sands. What is lacking in the analysis is the greenhouse gas emissions implications. A simple back of the envelope calculation is instructive. According to EPA calculations, a typical barrel of crude oil contains roughly 0.43 metric tons of carbon dioxide. This is the combustion emissions that would result from burning that crude. For average transportation fuels sold or distributed in the United States, combustion emissions account for 80 percent of well to wheel emissions (Lattanazio, 2014). Grossing up the combustion emissions for a barrel of oil, this means the well to wheel emissions of a typical barrel of oil consumed in the U.S. is about 0.54 metric tons. As noted by Max, the well to wheel emissions of Alberta tar sands are 14 to 20 percent higher than emissions of transportation fuels used in the U.S. Taking the upper end of this range, we have a well to wheels estimate of 0.64 metric tons per barrel of tar sand oil.

For every barrel of tar sand crude bottled up in Alberta, we have a net reduction in emissions (on average) of 0.64 – 0.54 = 0.10 metric tons. This assumes a low price elasticity of demand for oil such that the lost Alberta tar sands oil is replaced by greater production of domestic oil in the United States or increased imports of foreign oil (other than from Alberta). Whether the replacement oil has higher (think Venezuelan) or lower (think Saudi Arabian) carbon content depends on the source of the replacement oil. I’ll just focus on an average.

At 0.10 ton per barrel, bottling up 1 billion barrels of tar sand oil reduces emissions by 100 million metric tons in the 26 years to 2030. To put that number in perspective, global energy related carbon dioxide emissions were 32,579 million metric tons in 2011 (EIA). If global emissions are flat between 2011 and 2030 (an unlikely scenario), then the 100 million metric tons of avoided emissions from not building the pipeline are 0.012 percent of global energy related emissions over that period. Even if we take the most extreme scenario of bottling up 10 billion barrels, global emissions have been reduced by 0.118 percent over that time frame. That’s just over one–tenth of one percent of global energy related CO2 emissions. Put differently, it’s roughly the emissions we can expect from the island of Martinique assuming its emissions grow by two percent per year over the next 26 years.

Max raises some other interesting issues that could affect the analysis including the possibility of carbon taxation (yes!) or greater regulatory scrutiny of pipeline projects in Canada. I have no more insight on how regulatory oversight might unfold in Canada than does Max but will simply note that one possible outcome of a failure to build the Keystone XL pipeline is that political pressure in Canada will mount to approve existing (and possibly new) pipeline projects. That lowers the estimate on bottled up crude.

Now one might argue that reducing 100 million tons of emissions between now and 2030 (or even 1 billion tons using Max’s most restrictive scenario) is a good thing regardless of its share of global emissions. But before coming to that conclusion, I’d want to know a few things. Take, for example, implications for railroad transport. One possible outcome of not building the pipeline is displacement of current non-energy rail transported goods by more crude oil from Alberta. If that occurs, what costs might we incur in terms of (among other things) increased risks of railway related oil spills and increased costs of food and other rail transported products whose transport prices might increase in response to greater competition for scarce rail car space?

Hi Gib. I agree on all points. Also, the post simply dealt with the research question what will happen to Alberta oil sands production, not overall greenhouse gas emissions. Several commenters have “pointed” this out. The general equilibrium implications of this are most complex and certainly worth studying. Max

Hi both, I think this otherwise fine article misses a crucial point. Those of us opposed to Keystone XL believe that only a quarter to a third of currently identified petroleum (not bitumen) reserves can be used; the rest has to stay in the ground. Keystone XL is important to greenhouse gas emissions mainly because stopping it needs to be a turning point in the direction of a) no new additions to reserves and b) stranding most existing reserves, permanently. Additionally, developing the tar sands is an environmental crime of the first water – pun intended – due to the damage in Alberta, even if GHGs were somehow not an issue. If you revise this article, please mention these points.

I need to correct a small error in my previous post as there are (obviously) only 16 years between now and 2030, not 26. The thrust of my posting is unchanged but 1 billion barrels of oil represent 0.02% of global energy related emissions, not 0.012%. And the emissions equivalent of 10 billion barrels of oil are 0.192% of global emissions, not 0.118% meaning the Central African Republic represents a equivalent amount of emissions rather than Martinique.

While your argument looks accurate, you fail to compare what the alternative is. You compare the oil sands as 14%-20% more carbon intensive than the average transportation fuel, but is that its competition? My limited understanding is that the oil would be used in refineries that are currently using heavy oil from Saudi Arabia or Venezuela. I did a quick Google search and found this article from Motley Fool that shows the LCA for Canadian sands is ~6% above average fuel, while the other two are 11% and 14% more carbon intensive than average.

http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/03/02/advocates-for-the-keystone-xl-have-gone-about-it-a.aspx

So while we leave a billion barrels of Canadian bitumen in the ground, we may pull out an extra billion barrels from a more carbon intense source.

I would second this statement. At some point, the political situation in Venezuela will stabilize and the bitumen in the Orinoco basin will be extracted. The deposits in the Orinoco basin dwarf what is to be had in Canada. Unit production costs are likely to be much lower, since there is no environmental or renewable lobby in Venezuela voicing concerns about the manner in which the resource is extracted. The Canadians have a short window to ramp up production of bitumen before they face competition from Venezuela.

Hi Max, Nice write-up for perspective on the potential build-out of Alberta oil sands resources. If your numbers are correct and denial of Keystone XL Pipeline permit will keep an extra billion barrels of synthetic crude oil in the ground – it sounds like it DOESN’T really buy us MUCH time…50 days of US oil consumption. But a billion barrels of crude oil would take a lot of terrestrial carbon management to fully offset the added radiative forcing, actions we’re already crediting for anthropogenic GHG emissions. Hope you will be sending your comments to the State Department, reminding them of the President’s claim….if Keystone XL worsens our climate problem, it’s not in the interests of the United States (or any resident of this planet). The construction of Keystone XL Pipeline will lead to greater utilization of a higher carbon intensity crude oil, no doubt about it. The jobs claims and the domestic security claims are vastly overstated by TransCanada and other proponents of the project. In situ extraction of bitumen has significant problems, different than surface mining, but significant. And both methods of extraction are high LCA GHGs that worsen our climate problem. The U.S. needs to support investment in low-GHG forms of energy, supporting alternatives to petroleum is investing in our collective future. We don’t have time to continue investing in last century’s fossil energy dependence.

Max — your conclusion look s like a non seq. Are you saying that no Keystone will result in alternatives being developed or that the world is going to burn other fuels anyway?

Greetings from 36000 feet somewhere east of Cambodia. I am not sure I understand Dave… Keystone XL might lead to increased extraction of oil sands. Not permitting Keystone will not accelerate the development of alternatives noticeably. What I am asking for is a level playing field for all fuels – where we tax each fuel at its marginal external cost.

Max, as you have shown, the transportation capacity constraint on production seems to be an obvious and binding constraint on production. Do you have any insights into how the methods employed by the State Department either resolved or failed to address it?

Sam, they looked at the transportation markets but did not do the 2030 comparison here (or at least I did not see it).

It’s not clear if you have taken diluent into account. The bulk volumes transported in the pipelines are diluted bitumen, which is about 75% bitumen and 25% very light oil! added to allow the bitumen to flow. Correcting for this would mean that the transportation capacity of bitumen would be reduced still further.