Raising Gas Prices to Grow An Economy

Raising gasoline prices can increase efficiency, slow global warming, and grow the economy.

Two weeks ago, Yemen increased gasoline prices from $2.20 to $3.50 per gallon, while increasing diesel prices from $1.70 to $3.40.

And last month, Egypt increased gasoline prices from $.47 to $.83 (premium gasoline went from $1.00 to $1.40), while increasing diesel prices from $.61 to $1.00.

These are significant increases. The reforms in Yemen bring the price of both fuels up to market levels. And although prices in Egypt remain well below market levels, this is an important step toward rolling back subsidies in a country that has some of the largest energy subsidies in the world.

Economists, including myself, always complain about energy subsidies and celebrate in cases like this when subsidies get rolled back. But what is the big deal? What’s wrong with subsidizing gasoline?

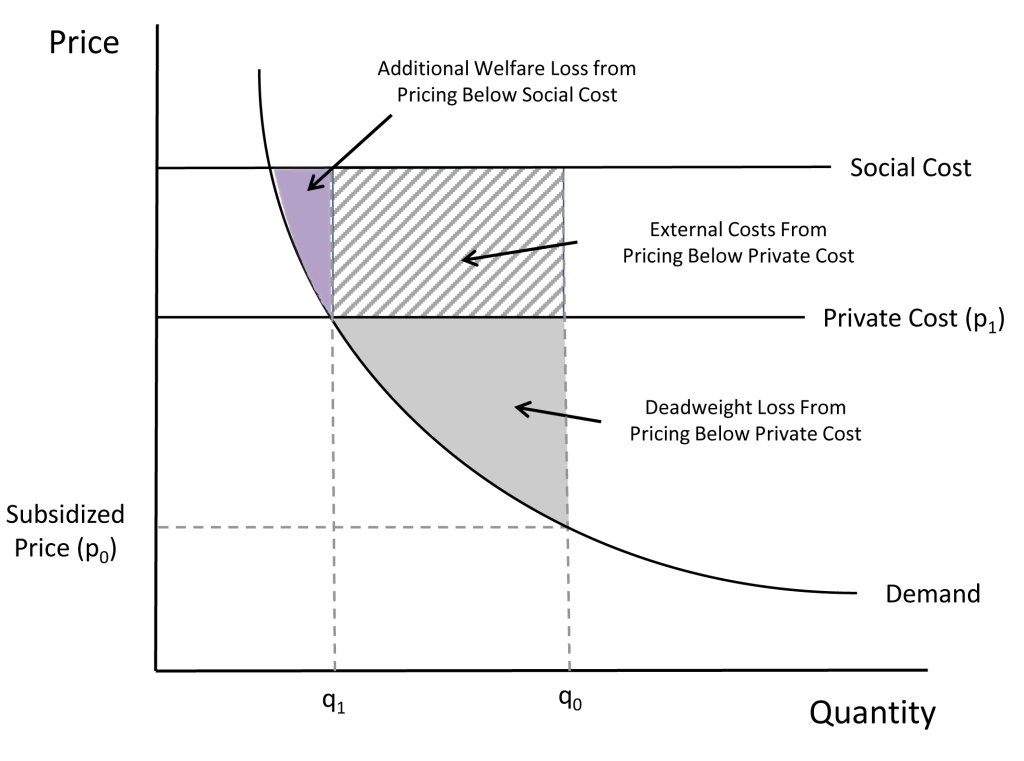

As I discuss in the video, the economic cost of fuel subsidies can be summarized by this figure, straight out of Econ 101.

If you are like most people, you tune out whenever anyone says, “deadweight loss”. But this is just economist-speak for waste. When prices are subsidized, gasoline and diesel end up being used in a whole host of low-value ways. People buy fuel-inefficient vehicles and drive them too much. They produce goods and services using inefficient, fuel-intensive technologies. And they consume too many fuel-intensive products.

Subsidizing energy shrinks the economy. The deadweight loss triangle means that it costs the economy more to supply this fuel than the value these consumers get out of consuming. So, with every transaction, economic value is destroyed. This is the opposite of gains from trade. This is losses from inefficient trade.

By my calculations, prior to the reform the deadweight loss from fuel subsidies in Yemen was $40 million per year. Total fuels expenditures in Yemen is $1.2 billion annually, so this is small compared to the size of the market. Worldwide, there are many countries with larger subsidies than Yemen. In fact, Yemen is not even in the top 20.

Egypt, incidentally, with much more generous subsidies and a larger population, was #5 in 2012 in terms of total welfare loss from fuel subsidies, behind only Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iran, and Indonesia. When I next redo these calculations, I expect to see Egypt slip back a couple of notches.

The price increases in Yemen and Egypt will also decrease the burden of pollution, traffic congestion, and vehicle accidents. A new IMF report finds that the total cost of externalities from driving exceeds $1.00 per gallon in most countries. By my calculations, removing subsidies in Yemen will decrease fuels consumption by 90 million gallons per year (a 15% decrease). So if external costs are $1.00 per gallon, this is $90 million annually in additional benefits.

Traffic jam near Sana’a, the capital of Yemen.

By the way, you might have noticed that there is a smaller purple triangle to the left of the externalities rectangle. To maximize welfare you really want to increase prices all the way to social cost. This would further decrease consumption, yielding this additional welfare gain. You can think of this as another deadweight loss triangle or, alternatively, think of the entire larger triangle as deadweight loss relative to the full social cost of fuels consumption.

(Yes, this is exactly the same as the discussion in California about including transportation fuels in the cap-and-trade program for carbon dioxide. See here and here. The whole point is to move California fuel prices closer to full social cost.)

There is more work to do in both countries. In Yemen, it will be important to once-and-for-all allow gasoline prices to float at market levels. These reforms have brought prices up to market levels, but if there continues to be price controls, these gains will erode over time with inflation. In Egypt, there is still a long way to go before market prices are reached. The price increases last month went through with relatively little public protest (here), but it remains to be seen whether President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi will be able to push through deeper reforms.

I’m not claiming that subsidy reform is easy. The IMF has some interesting work aimed at trying to better understand the political challenges and potential approaches for facilitating reform (here). But the economic analysis makes it clear that much is at stake. Pricing energy below cost imposes real inefficiencies, and these are enormous markets so the magnitude of the inefficiencies can be very large.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Raising Gas Prices to Grow An Economy” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, November 8, 2018,

https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2014/08/18/raising-gas-prices-to-grow-an-economy/

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

In regard to my comment above in regard to Iran changing from a subsidy for energy to making a monthly payment, the IMF economist I mentioned made a presentation in June to the National Capital Area Chapter of the U.S. Association for Energy Economics. It is available at http://ncac-usaee.org/pdfs/2014_06Zytek.pdf

In regard to the traffic jams in Yemen, I am reminded of the time of use tolls on some highways in California, particularly on Route 91 near Los Angeles. Nominally the pricing mechanism is able to adjust 168 different tolls, one for each hour of the week, plus special tolls for each hour of certain holidays. The tolls adjust upward quarterly so long as the traffic jam persists or in the case of Route 91 while traffic volume is still near the design limit. I mentioned the Route 91 pricing mechanism in my 2014 February 14 blog entry, Pricing Gasoline When the Pumps Are Running on Backup Electricity Supply, at http://www.livelyutility.com/blog/?p=263

I think the reason that I get so annoyed with so many of these conversations about fuel taxes is because they ignore the ultimate subsidy which truly drives over-reliance on single passenger autos with its concomitant “social costs”. That subsidy is free roads for autos to drive on. When I see the photo of the traffic jam in Sana’a, Yemen; I don’t see over-subsidized motor fuel; I see a finite resource(the roadway) which is given away, free of charge, to all comers. If that roadway were tolled at a market clearing price, then you would see vastly fewer single passenger autos and many, many more multi-passenger vehicles. Traffic would flow much more freely and vastly less motor fuel would be burned.

The problem with universal toll roads is that there is a significant network externality. The person driving isn’t the only one benefiting from the trip–the merchant selling the goods the driver will buy or the employer with the job for the driver also benefit. And the other individuals who will meet and interact with that driver also will benefit. How do we compensate them for what they lose when the network becomes less valuable? We have to be quite careful about how we choose to impose congestion tolls.

I struggle to see an externality. The road will cost more to use. As the costs of use rise, users will make substitutions for the individually driven auto. But, the network becomes more valuable because it is more productive. More individuals can use the network because it flows faster and the individual packets are more dense, e.g. five individually driven cars are removed from the network and replaced by a Jitney which can carry as many as twelve riders – each of whom pays a lower total cost per mile since they are not carrying the capital cost and operating expense of the individual auto. Travelers on the network pay lower travel costs because of the tolls. Merchants on the network benefit from faster delivery times and lower delivery prices because faster delivery times make common carriers more productive.

Think of a telephone call. Who benefits from the call–the person making the call or the one receiving the call. This became a huge issue when cell phones were just starting and the per minute charges were so much higher than for land lines.

The fact is that for local trips, that type of externality exists between merchants and customers and employers and employees. Yes, some will benefit from reduced congestion, but others will lose because making multiple stop trips that include transporting goods is more difficult. There is not a simple one-dimensional answer to this problem. I’m emphasizing that we need to consider all dimensions and not be dismissive of concerns by those affected. That’s a sure way to increase political opposition to what may be a good idea.

I am totally lost. Please elaborate. I am not being snarky, I want to know.

The ostensible purpose of tolling is to ration a finite resource by price. Generally, when you ration a resource by price, it will be allocated to its highest and best us first, then its next lowest use and so on. On any given roadway the least, best use is parking, next is single passenger transport. The higher better uses are going to be commercial and multi-passenger vehicles. Higher better uses will have denser capacities, economies of scale and higher rates of speed. Businesses and residents along the edge of the roadway benefit from denser capacities, economies of scale and higher rates of speed.

Please tell me who loses here.

Tolling is about addressing one externality, a negative one–congestion. I’m raising a second externality, a positive one-networking. Here’s a couple definitions and discussions of network externalities: https://www.utdallas.edu/~liebowit/palgrave/network.html and http://www.stern.nyu.edu/networks/30.html. For example a merchant sees increased value from increased customer access.

With a network externality, your ranking of value may not hold, and certain types of merchants are more likely to value single-person vehicle-minutes more than commercial vehicle-minutes because the former represent sales revenues while the latter represent goods whose value is dependent on the former arriving to make a purchase. All of this points out that this is a more complex analysis than a simple congestion externality, and a discussion well beyond what we can have in a blog.

Thank you for the links. The first one is a really good summary. Back to the particular case of a tolled road, Are you assuming that a tolled road will have fewer users in toto? Or do you assume that a tolled road will have fewer single person vehicles but the same number or more users in toto?

I don’t know the answer to that–I think that would be part of the assessment. The other issue however is how do you measure “users”? Someone on a jitney can’t carry as many goods as someone in a car, so that person may be less valuable to a merchant. This is all part of the assessment.

Is this so-called 2nd externality picking nits? Don’t the agents you’re introducing as relevant have pricing and contracting relationships that seek to address these networking values? Yes, cost allocation of fixed cost portions has always been difficult, but to raise the 2nd ext., if it really is an ext. and outside the marketplace, to the level of the 1st so as to argue that a price signal for the 1st is bad, … well, that’s quite a reach. Now if you want to raise a transaction cost issue about metering, collecting tolls, and cash-payers having to stop, etc. that’s more reasonable.

The positive networking externality is why we have public roads in the first place. In fact that externality has been so strong that toll roads have had difficulty gaining a toe hold anywhere until you get to a point where the congestion costs are so high that they outweigh the network benefits. London is good example; on the other hand even NYC doesn’t have congestion tolls in the US. Arguably the creation the FREE interstate highway system in the 1950s was one of the greatest boosts to the US economy in that period due to the network externality. To make a case for toll roads, the proponents must demonstrate that the congestion externality is more socially costly than the offsetting network externality benefit.

We don’t have untolled roads because, after some analysis, legislators determined that the network externalities of free roads were greater than toll roads. We have free roads as the result of a confluence of political, institutional and cultural forces over the course of a century. The fact that even NYC doesn’t have congestion tolls says nothing except that the forces against tolling are greater than those for tolling. If tolling traffic presents such negative externalities then why do we toll mass transit riders. Why not let them all ride free?

The forces against tolling are stronger precisely because of the positive externalities that we all enjoy thanks to the network of roads. No one conducted a formal analysis–not all (in fact very few) economic decisions are made because of explicit analyses conducted by PhD economists. However that does NOT mean that community leaders didn’t have a discussion about the notions of the benefits and costs. The debate over investing in the federal interstate highway system in the 1950s followed this model.

As for mass transit, we greatly subsidize all riders–no one pays even close to their true cost of service. In some places they do ride for free and many urban systems are gravitatiing toward and honor system (e.g., LA). Paying such a small fee is similar to a car owner having to purchase a vehicle and pay for gas to before entering the road network.

We don’t need a pricing system that always clearly identifies each component as being allocated for a particular function. Often the composite of prices act “as if.”

When we do this we also have to make sure that the impact of rising gas prices on lower-income people is mitigated. I don’t know how this can be done in a country with such a diffuse population without …. subsidizing gasoline! But it needs to be done to avoid piling one more hardship on their heads.

Most recent studies find that fuel subsidies are actually quite regressive, with the majority of benefits accruing to higher-income households. This book edited by Thomas Sterner is the most comprehensive study that I am aware of, and the evidence is pretty consistent across a wide-range of countries.

http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9781617260926/

It has also become pretty typical to combine gasoline price increases with increased funding for conditional cash transfer programs. This was the approach adopted last summer in Indonesia, for example.

A friend from the IMF worked with Iran when it dramatically reduced its energy subsidies. Iran used the increased revenue to give each person a fixed monthly payment.

In general, oil producers also consume more oil.

To argue that subsidizing oil consumption is associated with an absolute loss of welfare is probably incorrect. The OPEC countries, particularly Saudi, UAE, Kuwait and Qatar, have seen enormous gains in the terms of trade from increasing oil prices compared to a decade ago. GDP growth there has been very good, much better than, say, fuel-sipping Denmark or Finland. And that’s even with fuel subsidies for the exporting nations. Put another way, strength in oil markets allows those countries to squander part of the gains on consuming their own oil at below market prices.

But those days are over, and terms of trade will be deteriorating pretty consistently for the OPEC countries from here on out. Consequently, expect OPEC governments to progressively rein in over consumption over the next decade. Yemen won’t be the last country to cut subsidies in the near future.

“To maximize welfare you really want to increase prices all the way to social cost.” This, to me, is where the author jumps the rails.

Logically, if one argues that, via subsidy, the decreased price results in a deadweight loss; then logically, one should argue that taxing the good will also produce a loss for society. Logically, the market clearing price optimizes maximally or it doesn’t. If the market clearing price does not optimize maximally, then a subsidy will produce winners and losers and a tax will produce winnners and losers. Absent a proper accounting of the net gain or loss from either a tax or a subsidy, the author is engaging in spurious hand waving about social costs and deadweight losses.

Michael, by economic definition there is only one economically “correct” (meaning, optimal) price for a good/service X, and that is when the marginal price of X equals the marginal cost to society of consuming X (at equilibrium, ceteris paribus).

The author is precisely *on* the rails.